How did Minnesota become a hub for Hmong people?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

The top non-English languages spoken in Minnesota homes were once German and Norwegian. They are now Spanish and Hmong, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

That shift illustrates the prominence of Hmong culture in Minnesota today. Several readers wanted to know more about the origins of the state's large Hmong community. They sought answers from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project.

The Twin Cities boasts the largest urban Hmong population in the country. Hmong people are also the largest Asian group in Minnesota, with a population exceeding 94,000. In the U.S., most Hmong people live in Minnesota, California or Wisconsin.

Many Hmong people live in America today in part because they helped the United States fight communists during the Vietnam War. This later made them the targets of communist leaders in Southeast Asia, forcing Hmong people to seek refuge in America.

The federal government resettled many Hmong refugees in the Midwest, and social service agencies in Minnesota helped them integrate into society. The state's Hmong population expanded further as new immigrants sought to reunite with their family members.

The reason to leave

During the Vietnam War, the CIA conducted a "secret war" in neighboring Laos by recruiting Hmong people to aid U.S. forces fighting communists there.

The war in Laos was very different from the Vietnam War. Roughly 1,000 American service members and civilians participated. The fighting relied heavily on a CIA-supported army of up to 40,000 locals, including 22,000 Hmong people, according to the book "Refugee Workers in the Indochina Exodus, 1975-1982" by Larry Clinton Thompson.

The U.S. evacuated Laos in 1973 and communist-backed leaders took power two years later. The Hmong soon faced retaliation from communists for being allies with the United States.

Tens of thousands of Hmong fled Laos by foot or boat, crossing the Mekong River into Thailand. By 1975, many were living in a large refugee camp in Thailand known as Ban Vinai, just across the Laotian border.

Kao Kalia Yang recounted her family's 1979 escape from Laos in the book "The Latehomecomer," the first memoir written by a Hmong American published with national distribution.

Yang's family could not afford a raft across the Mekong River. Instead they had to float across it tied to a bamboo pole.

"My father had an idea," Yang wrote. "[H]e would cut the bamboo, tie it around himself, tie it to my mother and the baby, tie it to his mother, and he would drag them across. If they died, it would be together. If they survived, it would be together."

They crossed the river in the dark, hearing gunshots behind them. Born in 1980 at the Ban Vinai refugee camp, Yang spent six years there before migrating with her family to Minnesota in 1987.

The resettlement in Minnesota

Minnesota has a rich history as a destination for immigrants, notably the German and Scandinavian immigrants who arrived in the state in the 19th century. The number of foreign-born Minnesotans dipped in the mid-20th century, but later grew due to arrivals from other parts of the world — particularly Southeast Asia and Africa.

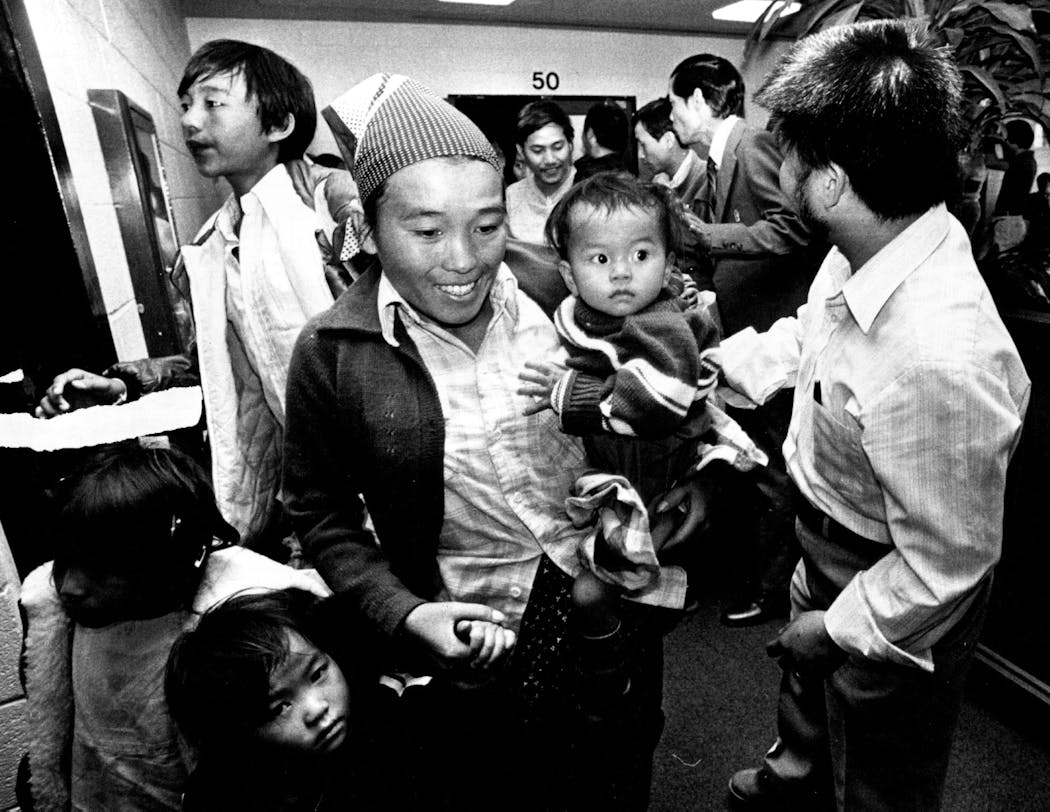

The first Hmong wave in the United States in the mid- to late 1970s was made up primarily of soldiers directly associated with U.S. war efforts. Under the policy of dispersal, the government tended to scatter Southeast Asian refugees across the country to help them assimilate and minimize the impact of large groups arriving at one time.

Hmong refugees initially resettled in several places, especially the Midwest, where weather and topography were very different from the tropical mountainous regions they once called home.

The passage of the Refugee Act of 1980 resulted in a second wave of Hmong immigrants. The law established a more robust support system for resettling refugees in the country, from employment to housing.

A desire by early refugees to reunite with relatives helped drive the second wave. Bonds between family members are especially strong in Hmong culture because of a clan structure that emphasizes shared ancestors.

In addition to family unification, Hmong people were drawn to Minnesota by employment opportunities, access to public housing and welfare benefits, according to a 1984 Hmong resettlement study.

MayKao Hang, who is now dean of the Morrison Family College of Health at the University of St. Thomas, shared her family's resettlement experience with the Hmong Oral History Project in 2012. Moving to St. Paul in 1976, her family depended on welfare support while living in public housing.

Years later, her parents helped shape the Hmong community here. Hang's father cofounded a number of Hmong organizations, including the Hmong Cultural Center.

"I have really seen this community both as a kid and I think as an adult go through lots of change," Hang said.

Resettlements also rely on voluntary agencies, which provide refugees with initial housing, essential furnishings, food and clothing for the first 90 days after arrival. Such agencies in Minnesota include Lutheran Social Service, Catholic Charities and World Relief Minnesota. These groups also help with training in English language and employment skills.

The role of these agencies earned a mention in Clint Eastwood's 2008 film "Gran Torino." In one scene, Eastwood's character tells a Hmong girl, "I don't know how you ended up in the Midwest, with snow on the ground six months out of the year."

"Blame the Lutherans," she responds. "They brought us here."

'All our children can succeed'

Hmong people in Minnesota today earn slightly more than the statewide median household income, according to a 2023 report from the state demographer's office. Disparities remain in education, however, with 20% of Hmong adults over age 25 lacking a high school diploma or equivalent. That's higher than the statewide average of 6%.

Decades after Hmong people first settled in Minnesota, many have become leaders in the state.

A number of Hmong people have held positions in local and state government, including former state Sen. Mee Moua, the first Hmong American to serve in the Minnesota Legislature. Gymnast Suni Lee made history as the first Hmong American to make the U.S. Olympic team and win an Olympic gold medal, at the Tokyo games in 2021.

Lee's victory spurred hundreds of people to greet her at the airport and thousands more to celebrate her accomplishment in a St. Paul parade.

"The Hmong community has lost so much throughout history," Bo Thao-Urabe, one of the attendees at the airport event, told the Star Tribune at the time. "Her win shows what's possible when a community is given opportunity and support. All our children can succeed."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why did Scandinavian immigrants choose Minnesota?

How did the Twin Cities become a hub for Somali immigrants?

Why did Finnish immigrants come to Minnesota? (And no, they're not Scandinavian)

What are the top five immigrant groups in Minnesota?

Does Minnesota have the coldest and longest winters of any of the US states?

Why are vehicle tabs more expensive in Minnesota than in other states?