Long before it became a national obsession and a whole season unto itself, the NFL draft was, well, boring, quiet, largely ignored and little more than a good idea hatched in 1936 by a fledgling league to stifle player salaries.

"Mock drafts" were words unwritten until the 1950s when articles began to explain how some teams prepped for the unlimited possibilities of the annual selection process. The news media followed slowly with its own versions as early as 1969 when Carl and Pete Marasco, insurance-selling brothers out of Philadelphia, talked Pro Football Weekly publisher Arthur Arkush into running their player rankings.

"Not to sound arrogant," said Hub Arkush, who succeeded his father at Pro Football Weekly, "but I think we invented all of this."

Other draftnik pioneers, including legendary Joel Buchsbaum, a nerdy Brooklyn recluse who became one of Bill Belichick's best friends, carved a path through the 1970s. That led Chet Simmons, president of a brand-new cable network called ESPN, to approach NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle with a proposal to broadcast the 1980 draft. Rozelle, the greatest pitchman in NFL history, was dumbfounded.

"Pete thought it was funny," said Joe Browne, who worked in the league office for 50 years. "He couldn't understand why someone would want to televise him reading picks. None of us could."

Meanwhile, a teenage college dropout in Baltimore was just beginning to build a draft analysis empire like no other in his parents' basement. Four years later, 23-year-old Mel Kiper Jr. was on his way to Bristol, Conn., for an interview with ESPN. He brought with him an unsurpassed work ethic; an unmatched ability to speak quickly, clearly and endlessly, and, of course, a ready-made head of hair that has stood the test of time.

"They hired me in 1984, and everything I did that entire first year — the draft, the "SportsCenters" — I made 400 dollars. Total," Kiper said. "Four hundred dollars. But they hired me. And the rest is history."

The 2024 draft, which begins Thursday, will mark Kiper's 40th anniversary. Now making more than 1,000 times his 1984 salary, Kiper still does mock drafts. Then again, by now, thanks to the internet, so does everyone else.

"We've become like mock central in this country," Kiper said. "But I get it. Mock drafts are fun."

Draft's humble beginnings

Four of the first 11 draft picks in NFL history in 1936 never played in the league, including No. 1 overall pick Jay Berwanger, who took a job with a Chicago rubber company when his salary demands weren't met.

NFL scouting was primitive to nonexistent in those days. Good example: In Pittsburgh, the Steelers heard about a man named Ray Byrne, a local third-generation undertaker with an odd hobby of gathering information on college prospects. They hired him in 1946 with a written agreement that, "Ray can drop his football duties and become a mortician whenever necessary," according to an article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

"I started writing about the draft in the '60s for the San Francisco Examiner, and it was all I could do to get 10 inches of copy in the paper because nobody cared," said Frank Cooney, also the founder of NFL Draft Scout. "Little by little, it grew. Eventually, the idea of a mock draft came up. I remember thinking, 'What a stupid idea.' "

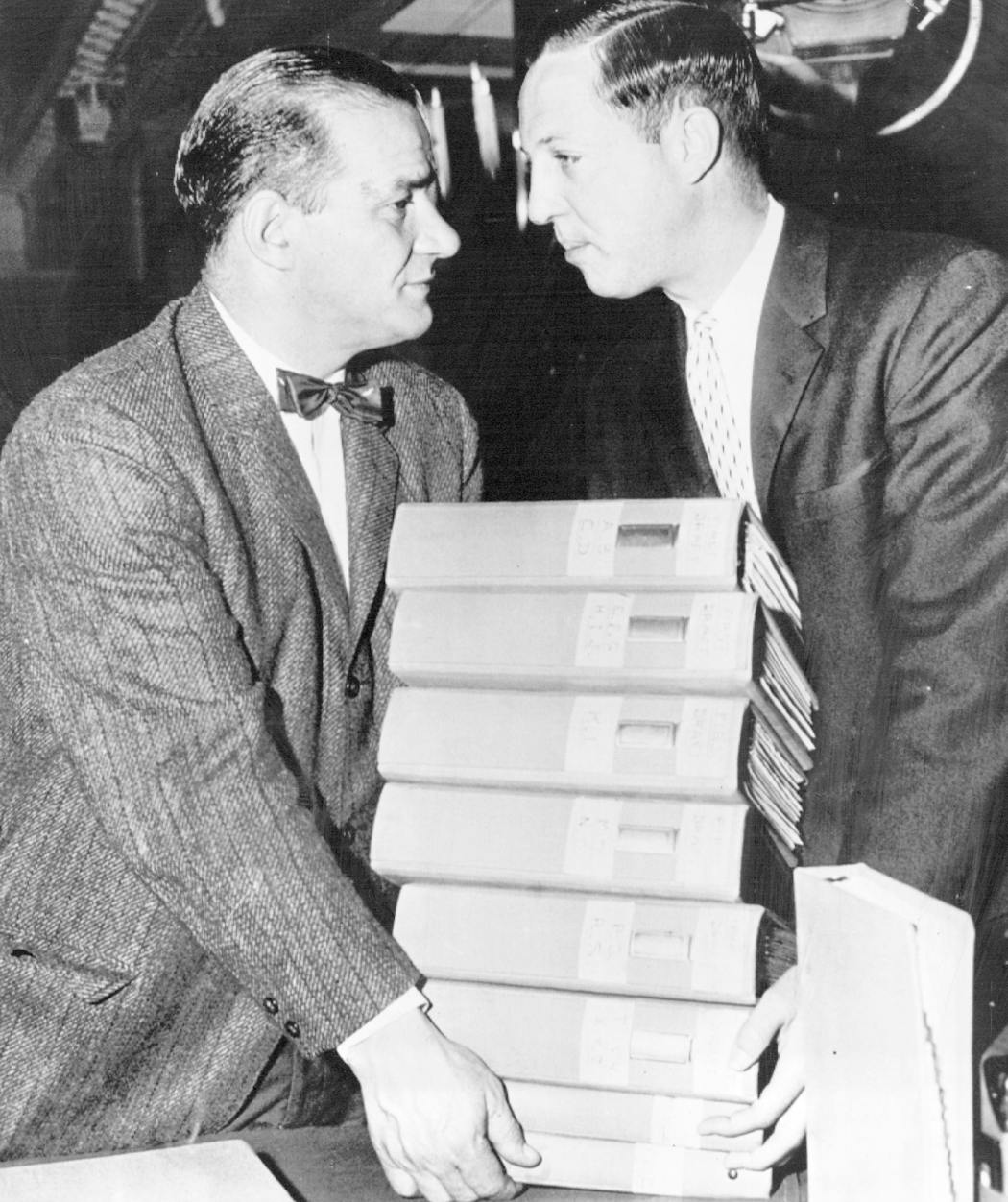

The rival American Football League arrived in 1960, creating a seven-year, no-holds-barred battle for college players with the NFL until the merger and the first common draft in 1967.

"We'd hold the draft in the fall at the Summit Hotel in New York City," Browne said. "It wasn't open to the public. Only a few newspaper reporters were there, and no TV. Down the street was the Belmont Plaza, where we had another setup that was confidential."

That's where the NFL stashed its top college prospects and assigned "babysitters" to keep them away from AFL poachers. Rozelle wouldn't announce a pick until he was reasonably assured the player would actually sign with the NFL.

The 1965 NFL draft was held Nov. 28, 1964. The AFL held its draft the same day via conference call. Ron Wolf was working for AFL renegade Al Davis in Oakland. Davis had his own babysitters.

"We had a tackle from Memphis named Harry Schuh," Wolf said. "His last game that fall was in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Al had the perfect plan."

Schuh and his family were flown to Las Vegas to be babysat until the Raiders could draft and sign him. The Lions of the NFL found him.

"Al had another person go to Vegas and fly Harry off to Hawaii," Wolf said.

Schuh, selected third overall by the AFL, played for the Raiders for six of his 10 years in the league.

The 'Godfather'

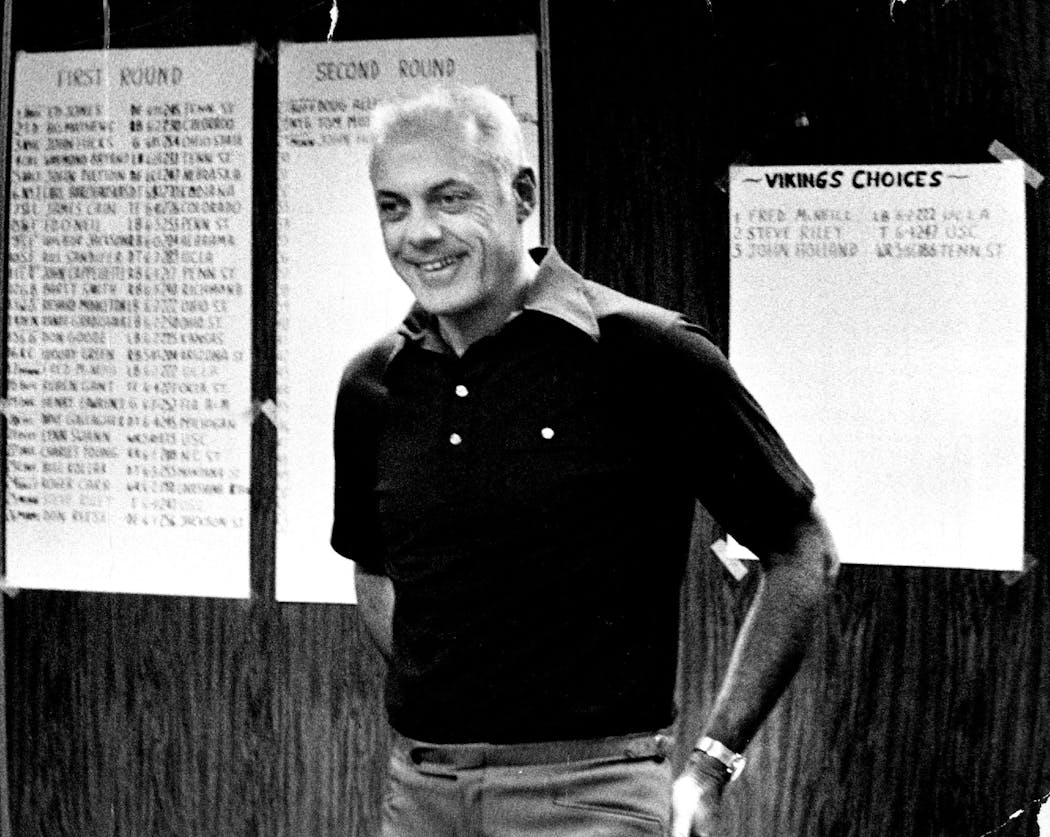

Interest in the draft increased in the 1970s, creating early draftniks besides the Marasco brothers. Palmer Hughes was a teacher in Brooklyn. Joe Stein worked for the Sporting News. And a man named Jerry Jones — no, not that Jerry Jones — was so good at privately forecasting the first two rounds of the 1971 draft that he went public the next year with "The Drugstore List," which got its name from Jones' day job as part-owner of Horton's drugstore in Mariemont, Ohio.

Meanwhile, an oddball teenager named Buchsbaum wouldn't quit hounding Pro Football Weekly for a job after the Marasco brothers had left for the NFL.

"Joel was the most different human being I've ever met," Hub Arkush said. "He wore us down. We finally gave up and said, 'Go ahead, show us what you got.' Everything he did was handwritten. It turned out he really knew his stuff."

He knew it so well that Pro Football Weekly published its first separate "Draft Guide" book in 1979. It became the bible for fans and a nation of reporters who started covering drafts.

"All of this stuff we see today, mock drafts, Joel started it all," said longtime NFL reporter Rick Gosselin. "He's the godfather."

Buchsbaum lived alone and rarely left his cramped Brooklyn apartment, which Arkush described as "pretty close to what you see on 'Hoarders.' " Unapologetically disheveled, Buchsbaum stood a tad shy of 5-9 and weighed little more than 100 pounds because of food allergies and days on which he'd forget to eat because he was so engrossed in watching film and ringing up a $1,500 monthly phone bill talking to a league of decisionmakers who not only respected him but sought out his knowledge. Belichick tried to hire him in Cleveland and New England.

"Bill told him he'd pay him more money than he could imagine," said John McClain, a longtime NFL reporter in Houston. "Joel said, 'No thanks, I feel like I work for all the teams.' "

Buchsbaum's nasally Brooklyn accent became famous on radio stations.

"I did radio with him in St. Louis, and people wondered if he was real or computer-generated," said Howard Balzer, former pro football editor of the Sporting News. "I also did the ESPN telecast in the early days. We had him on the air in 1982. He was telling us to keep an eye on Jeff Bryant, a defensive lineman — who wasn't on anybody's radar — as a first-round pick. We were like, 'No way.' "

Bryant went sixth overall. But Buchsbaum's untelegenic appearance ended his TV career as soon as it started.

"Joel's wearing a Notre Dame sweatshirt, scraggly hair, looking like he hadn't slept in a week, which he hadn't," Balzer said. "I remember as he's talking, a producer is in my ear saying, 'Never again.' "

Buchsbaum died at 48 of a heart attack in 2002. A memorial service was held for him at the NFL scouting combine. Davis was there. So were 12 general managers, 60-some scouts and seven head coaches, including Belichick, who asked to speak.

"Bill got up there," Arkush said, "and the first thing he said was, 'Joel Buchsbaum was my best friend.' "

'Goose' was golden

Gosselin's first mock draft for the Kansas City Star was 1986. His last one for the Dallas Morning News was 2011.He would spend 18 hours a day building his own draft board and working the phones with a network of 130 league sources. They knew not to double-cross him, or they'd be out of his vaunted loop.

"I would have teams call me when they were on the clock to make sure they were clear on a guy," said Gosselin, who once nailed 18 first-round picks.

Times were different in the '80s and '90s. The NFL was more open, less paranoid. And, frankly, as Gosselin said, "Reporters also weren't running to Twitter with everything they would hear."

"I'd be in the head coach's office pouring a cup of coffee as he's watching film," he added. "You can't do that today."

Gosselin is the person who pointed Belichick to a little-known Kent State quarterback named Julian Edelman as a late-round punt return prospect. Belichick was eternally thankful and also puzzled that none of his scouts knew what Gosselin knew about Edelman.

'We were losing money'

Kiper was 18 and going to Essex Community College for broadcasting when he started sending his draft reports to NFL teams in 1979. He formed a bond with Ernie Accorsi, the Baltimore Colts' assistant general manager at the time, and still has the letters of praise he got back from the likes of Bill Walsh and Don Shula.

"My father said to me, 'Hey, you're doing this draft report, you're doing 20 to 25 radio shows a day. You have to decide between this and college because you can't do both,'" Kiper said.

He made what at the time was the riskier decision.

"We weren't making money. We were losing money," Kiper said. "My dad invested 15, 20 grand into the business. The first year we made the book available to the public in 1981, we had 120 subscribers. Then 500. Then 1,500. And it kept growing, and then everything just took off."

Indeed, it did.

RandBall: If Chris Finch wants to 'lengthen the rotation' he is free to do so

Twins-Athletics series preview: Pitching probables, injury report, TV-radio information

Gophers football recruiting tracker: P.J. Fleck reels in five more

McKaylen Lewis set a state meet record in track and field. This year, getting back has been a journey.