'I felt desperate': Journey from Ecuador to Minnesota marked by poverty, exploitation and hope

Patricia fled Ecuador and trekked through the jungle, crossed eight countries, spent several days in immigration detention near San Diego and took a four-hour flight to Minneapolis. By the time she walked out of the airport this spring, the mother of three was crying. She missed her children.

"Tranquila," said the Ecuadorian man who came to pick up Patricia. "Don't worry. Everything's going to be all right."

He hugged her, and Patricia, 39, settled into the man's SUV with a family she had met weeks earlier at a bus stop in Ecuador. At a sprawling house in southeast Minneapolis, he showed her to a room where two other migrants shared a mattress. Rent was $800 each.

Patricia worried how she would pay for housing and the debts she owed for airfare and help crossing the Mexican border. The man gave her fake Social Security and green cards and said she could look for work on Central Avenue in northeast Minneapolis, an Ecuadorian hub.

The journey had been hard, but Patricia, who didn't want her last name used because she feared retaliation from the man, found that her troubles persisted.

She didn't speak English. She didn't know anyone here. She and the other Ecuadorians had come to escape poverty and oppression — but at what cost?

'A lot of pain in that jungle'

Ecuadorians line up on Central Avenue to send money back home and find jobs. At one church, so many Ecuadorians fill the pews that dozens have to stand in the back. Demographers estimate Minnesota's Ecuadorian immigrant population grew more than 56% between 2007 and 2021 to at least 8,155 residents.

The numbers keep growing amid Ecuador's collapsing economy and rising violence. The federal immigration court at Fort Snelling went from only a few hundred Ecuadorians a year to 4,576 pending cases by mid-2023 — a twelvefold surge since 2018. Ecuador is now the most common nation of origin for pending immigration cases in Minnesota.

Near the Ecuadorian capital of Quito, Patricia said she faced discrimination and violence as an Indigenous woman. She and her family were beaten, called names and denied jobs. She made a meager living driving cabs and buses. It was too expensive for her whole family to leave, but she said her husband urged her to leave on her own after her boss abused her; he would stay with their three children.

The Biden administration announced in April a campaign with Colombia and Panama to stop record migration through the Darien Gap and crack down on human smuggling. Weeks later, Patricia left home. She met a man with his family at a bus stop in Quito. They were headed to a place called Minneapolis.

"They asked me if I wanted to come with them … and [said] they would help me," Patricia recalled.

She rode with the group to Colombia, took a boat into Panama and began walking through the lawless, mountainous jungles of the Darien Gap, where Central and South America meet. Patricia passed dead bodies. She saw children crying of hunger and broken ankles. At night, Patricia fell asleep on the ground, under a sheet of plastic to protect against bugs.

"There was a lot of pain in that jungle," Patricia recalled.

She lost the family in Costa Rica, and continued traveling solo through Central America on buses. A cousin who was going to help Patricia in Tennessee stopped communicating.

In southern Mexico, Patricia reconnected with the man from the bus stop. For $150 he helped her cross the country to Tijuana. For another $1,000, the man's brother helped her over the border. Her family back in Ecuador raised $700 of that by selling a TV and other items. She promised to pay the rest when she found work.

She entered the U.S. on May 9 and presented herself to immigration authorities, with the intention to apply for asylum. Patricia was briefly detained, then released with an order to appear in immigration court on April 17, 2024.

Opportunity and despair

Anna Gerdeen met Patricia and her fellow migrants on the plane from San Diego while returning from vacation. She serves as executive director of the Camden Collective, a food shelf in north Minneapolis that helps an increasing number of Ecuadorian and other Latin American migrants.

Over the next few weeks, she bought Patricia an iPhone, clothes and meals. She invited her to her North Side home and slowly learned her story. Gerdeen grew concerned that Patricia was being exploited.

Patricia found that she was one of 17 migrants in the house. She was taken aback at the high rent, but had nowhere else to go. "I felt desperate," Patricia recalled. Her roommates worked at a packaging plant with their fake papers, but the company had no job for her.

She said the man told her she owed $4,000 for the plane ticket, rent and migration help, and couldn't move out until she paid it. Gerdeen helped Patricia negotiate it down to $1,500 and told Patricia never to use the illegal work documents — asylum-seekers can apply for work permits six months after entering the country. Patricia had a better chance of winning her case than most Ecuadorians because she was a member of a persecuted ethnic minority.

Patricia spent 12 days in the migrant house before Gerdeen persuaded her to live in her basement for free. The wife of the man Patricia met at the Quito bus stop — the sister-in-law of her lender — texted her a warning in Spanish.

"Be careful," the message said. "Don't be telling people about the work permit and don't say anything about this house."

Gerdeen and Patricia went to Fort Snelling to speak with Homeland Security agents and report the illegal work papers. The Star Tribune is not naming Patricia's lender because he has not been charged with a crime.

Patricia knows she is more fortunate than most migrants.

"I got lucky in meeting someone who has a noble heart. … Not everybody has that same kind of luck," Patricia said.

'Ugly to be here alone'

New migrants stream into Rosa Vasquez's salon on Central Avenue for a haircut before looking for a job. Some want to work under the table while awaiting their asylum cases, though the vast majority are unlikely to have winnable claims because they are fleeing general hardship instead of any legally defined persecution.

"The American dream is being sold poorly," said Vasquez. "I'm seeing a lot of frustration because they come here and there's not as many jobs as they think."

Some never present themselves to the authorities at all — like Diana, who arrived in late 2021 and didn't want her last name used because she is undocumented. She is almost done paying off her $36,000 coyote debt with earnings as a house painter.

"The only way that I think that you can stop immigration from Ecuador to the United States is that we need a leader that knows how to govern our country," Diana said after a service at Sts. Cyril and Methodius Catholic Church in northeast Minneapolis, where her 13-year-old daughter had just received first communion. "Because every day [in Ecuador] is getting worse and worse."

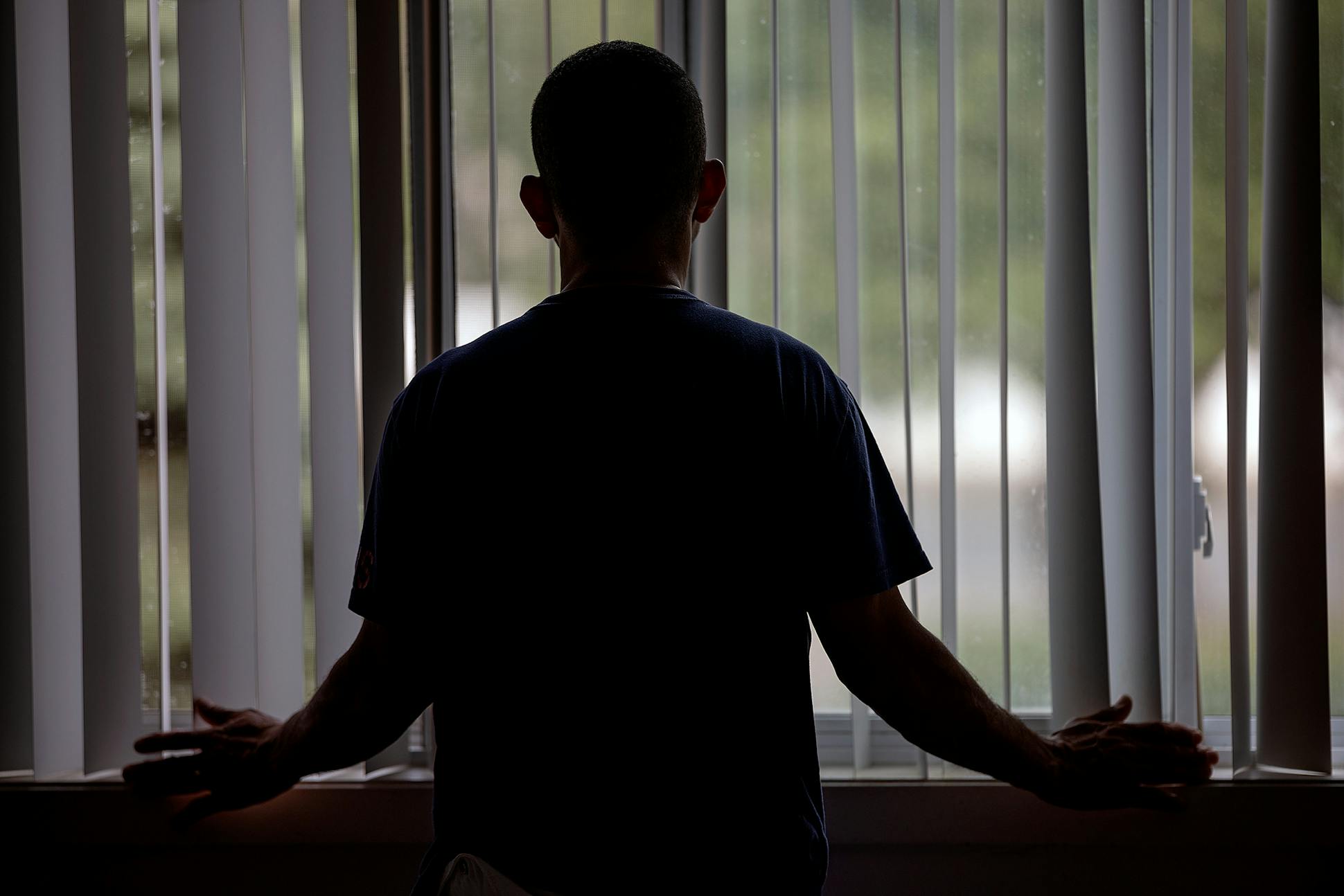

Jorge narrowly escaped a mudslide in the jungle that killed four people. He thought he caught a break in Minnesota when a Guatemalan took him to work at a construction site. But the man disappeared after three days and never paid him.

"It's ugly to be here alone," Jorge said, holding back tears. He did not want his surname published because he is trying to work without legal permission. "It's really difficult to get a job without documents and there's no help."

'Estoy bien'

The Ecuadorians gather outside Gerdeen's food shelf hours early on Saturday mornings. Patricia works there unloading boxes and welcoming Spanish-speaking migrants, offering encouragement.

She and Gerdeen have formed a deep friendship living together. Gerdeen teaches her English; Patricia reminds her to eat when she works too hard. In her new room, a decoration on the windowsill says "Minnesota Miracle."

Patricia recently called her parents in Quito. Joyful voices boomed over the phone.

"Como estas?"

"Bien, mami. … Bien, papi. Estoy bien."

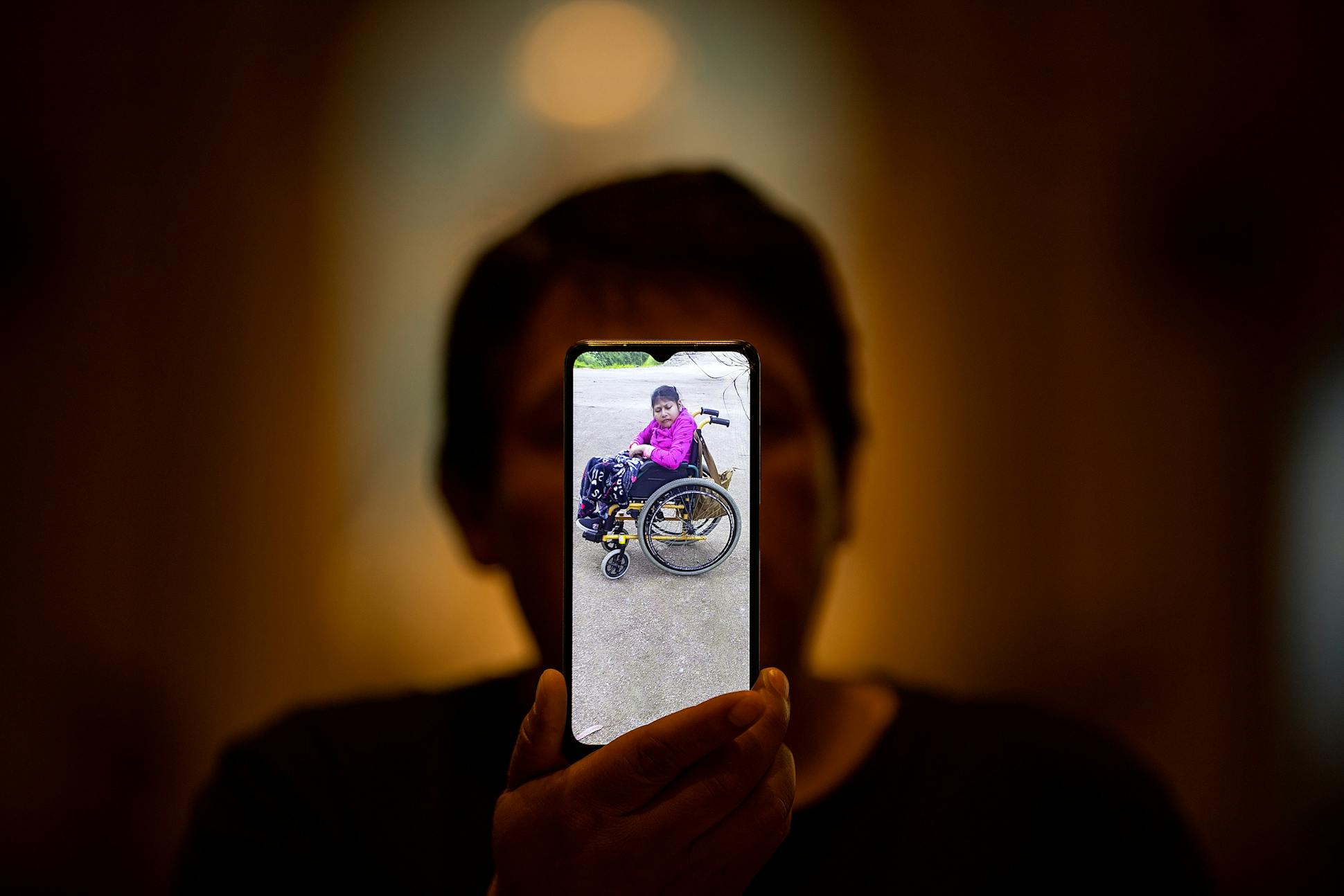

Her 5-year-old daughter came to the phone.

"Hola, mi amor!" said Patricia, and Gerdeen leaned into the video frame to wave. "Behave and eat all the food they give you. … You need to brush your hair!"

Patricia cried as soon as she hung up.

Meanwhile, a car recently rolled up to Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport to pick up a new group of Ecuadorians.

"Greetings, greetings," a man said in Spanish on the Facebook livestream to more than 2,500 followers. "There they are. ... The warriors who just arrived without incident to the United States." He ushered them into his car. "Get in, let's go."

It is the same man who picked up Patricia from the airport. His Facebook page — where he promotes justice for indigenous Ecuadorians— features videos showing the Ecuador-to-Minnesota pipeline and the happy life awaiting here. He posts footage of a family with children celebrating a birthday at the house in southeast Minneapolis; on another occasion, he and a friend clink Coronas in honor of a fiesta for St. Ignatius.

"Please," an Ecuadorian man posted, "help me get to where you are at."

Interviews with migrants were conducted in Spanish with photographer Elizabeth Flores interpreting.