It began with a question: "On Oct. 22, 1989, did you kidnap, sexually assault and murder Jacob Wetterling?"

"Yes, I did," Danny Heinrich said.

The hushed courtroom — packed with family members, reporters and law enforcement officers — began to buzz. Sitting in the front row, Patty and Jerry Wetterling listened, stoically at first, as Heinrich described that warm October night.

How he spotted the three boys on the dead-end road. How he put on a mask and reached for his revolver. How he warned Trevor and Aaron not to look back.

With a clear, low voice, Heinrich said he then handcuffed Jacob and put him in the passenger seat. At that point, the prosecutor asked, what did Jacob say to you?

" 'What did I do wrong?' " Heinrich answered.

A few in the courtroom gasped. Several began sobbing.

After 27 years of questions, Jacob's parents, the courtroom and all of Minnesota were suddenly confronting, in excruciating detail, the ugly answers to what exactly happened to their 11-year-old boy. A boy who loved football and peanut butter and believed things should be fair.

Heinrich recounted how he brought Jacob to a grove of trees and had him undress and how, when a patrol car passed, he panicked and pulled a revolver from his pocket. "I loaded it with two rounds."

Heinrich paused between words. He cleared his throat.

The courtroom was filled with people connected to Jacob: his brother, Trevor, and his sisters were among those wearing white "Jacob's Hope" buttons. Alison Feigh, a middle school classmate of Jacob's, wiped away tears. Near her, Joy Baker, the blogger whom Patty Wetterling credited with being "absolutely pivotal" to helping solve the mystery, took a few deep breaths.

Heinrich told the court that he acted alone. Then assistant U.S. Attorney Steve Schleicher brought up another date, another boy.

"On Jan. 13, 1989, did you in Cold Spring, Minnesota, abduct and sexually assault Jared Scheierl?"

As he said "January 13," Scheierl, now a 40-year-old man, looked down. Sitting in the front row, he listened as Heinrich admitted to "driving around Cold Spring, looking for a child." As Heinrich described the assault, Scheierl grimaced.

Scheierl had, for the past few years, told the story of the assault publicly, with the hope that it might help the Wetterlings find answers. Last year, authorities linked Heinrich to the sexual assault through DNA testing of the sweatshirt Scheierl was wearing when it happened.

Why, Schleicher asked, did Heinrich keep some of Scheierl's clothing?

"Souvenir," Heinrich said.

More gasps from the gallery.

U.S. District Judge John Tunheim asked Heinrich several questions, running through the details of the plea agreement. He explained the sentencing, set for November. Three courtroom artists, sitting in the audience, added detail to their sketches. In them, Heinrich, newly shaven, wore glasses and a light tan shirt over his pudgy frame.

And then it was over.

As they passed through the back doors of the courtroom, many relatives and family friends again began crying. They hugged one another, not quite ready to leave, yet. One woman released a strange, soft scream.

Bill Bronson clutched the window and sobbed. He grew quiet, said a few words to friends, then began sobbing once more. His fists clenched, he pounded the wall.

Bronson, 70, has known the Wetterlings since their children were small. His wife, he said, babysat the Wetterlings' oldest when Jacob was born. "I am consumed with anger," he said. "Why? Why? For the family and everybody to have to sit and listen to him, what he did to Jacob. ..."

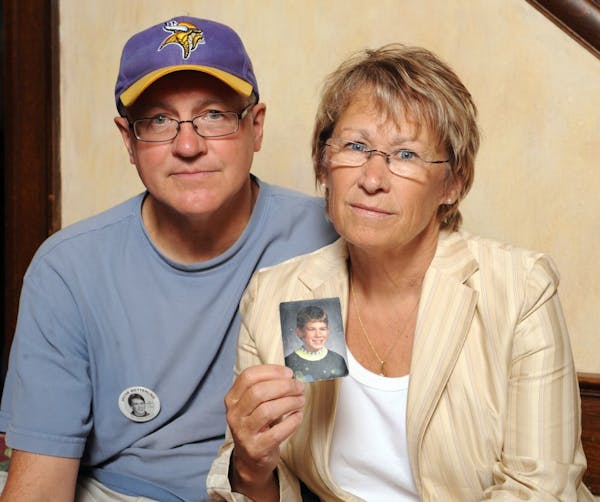

Beside him, Fran Larson shook her head. She was thinking of her son, Aaron, who had been biking home with Jacob when he was taken on that October night. "There's really no words for it," she said. Her husband, Vic, nodded.

Before the hearing, Aaron had "seemed very anxious to get answers," Fran Larson, 62, said. "But right now, it doesn't seem good. It seems painful."

"You give up something to gain something, I guess," Vic Larson said.

What was gained? Vic paused. "We got Jacob back."

Jenna Ross • 612-673-7168

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?