One of Neel Kashkari's unofficial barometers of inflation is a big tray of frozen lasagna.

It's become a staple in his household, enough to cover two meals for his family of four. The price can vary at stores, he points out, but at the Lunds & Byerlys where he regularly shops, the Stouffer's party-size meat lasagna used to be about $16.

"It went up to about $18," he says while pushing a shopping cart on a recent Saturday. "And then I think the prices leveled off for a bit. It will be interesting today to see whether the price has come down or the price has continued to go back up."

He finds the answer in the freezer section: $20.99.

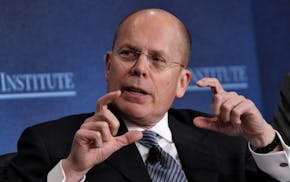

Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, will have a vote this year on how high interest rates go in the Fed's ongoing fight against inflation. So his views on whether price increases are cooling off fast enough will be closely watched as the economy hangs in the balance.

He's already indicated that he may push to move rates higher than some other members of the Fed's rate-setting committee.

It's a notable shift for a policymaker who had a reputation at the Fed, until recently, of being the most resistant to raising rates. He started moving in the other direction last year as inflation soared at the highest rate in four decades. Since then, price increases have been slowing down, but still remain at elevated levels.

The debate among Fed officials this year will be how much more to raise rates to bring inflation down, with the tradeoff being higher unemployment and a possible recession.

For Kashkari, he sees a greater risk if the Fed doesn't move rates high enough.

"If we don't do enough, and inflation becomes embedded and inflation expectations climb, that could take years to bring the economy back into balance, and that's very costly and very damaging."

'Sticker shock'

Kashkari's weekly grocery shopping trips, which he started doing for his family after the pandemic hit, have been a frequent reminder for him of the higher prices that Americans have been grappling with on a daily basis.

As he weaves his way through the store, he sees plenty of other examples of inflation as he picks items from the handwritten shopping list his wife jotted down that morning.

Bananas. Broccoli. Bacon. Milk. Butter.

Some of those items have doubled in price, he notes, roughly recalling the pre-pandemic prices.

"It's sticker shock," he says, shaking his head while in the checkout lane.

Similar to gas, food prices can fluctuate more than other goods and services. Kashkari has seen some grocery items beginning to drop in price. But in other cases, he says, the higher prices might be around for a while.

"A lot of the prices that we're seeing now are probably going to be with us," he says. "Hopefully they come back down, but more likely they're going to stop climbing."

From dove to hawk

Kashkari has an eclectic résumé. An engineer by training, he worked for Goldman Sachs and was a Treasury Department official in charge of the big bank bailout during the 2008 financial meltdown. He's dabbled in politics, unsuccessfully running as the Republican candidate for governor of California in 2014.

Two years later, he became president of the Minneapolis Fed, quickly becoming known as an outspoken Fed official who often posts on Twitter — though not as much lately as he used to — and who isn't afraid of standing apart from the rest.

Kashkari serves on the Fed's rate-setting committee but only gets to vote on it every three years. The committee has 12 voting members, including eight who are permanent and another four who rotate every year among 11 regional bank presidents.

In his first year having a vote, during a time of low inflation in 2017, Kashkari opposed all three rate hikes, saying there could be room for more job growth. He was the lone dissenter in two of those three meetings, cementing his reputation as one of the Fed's biggest "doves."

Fast forward to this year and Kashkari finds himself on the other side of the spectrum as one of the more hawkish members of the committee, projecting higher interest rates than others in order to rein in inflation.

He disclosed in a recent essay that he recommended raising rates at least another percentage point over the course of the next few meetings to 5.4% this year, higher than the 5.1% median projection of other Fed officials. He added that rates may have to go even higher than that.

"The economic conditions have changed," Kashkari said of his changing view on rates. "If I was always dovish no matter what, I wouldn't be a very good policymaker. How can that possibly be the right answer for the economy no matter what's happening in the economy?"

"We're all just looking at the data and trying to make the best read that we can."

Still, his shift has been surprising to some observers such as Claudia Sahm, a former Fed economist.

"It's jarring," she said. "He's gone from like really far in one direction to really far in the other."

And, she added, Kashkari continues to be fairly hawkish on rates at a time when inflation and wage growth has been cooling off.

Lowering demand

Since hitting a recent year-over-year high of 9.1% in June, the U.S. consumer price index has been easing, rising 6.5% last month. The Fed's target for inflation, using a different index, is about a 2% annual rise in prices.

Despite the recent promising data, Kashkari says the Fed needs to keep its foot on the gas pedal until it's convinced inflation is indeed being tamed.

"We hope inflation is slowing down, that it is decelerating," he said in an interview before the December inflation data was released on Thursday. "But we've been fooled before. ... So let's just get to a place where we're convinced that inflation is no longer climbing."

Then, he said, the Fed can pause rate hikes and allow their full effect to work through the economy, which will probably take a year or so.

After being slow to respond to the rise in inflation and initially dismissing it as "transitory," Fed officials spent 2022 catching up, aggressively hiking the federal funds rate from near-zero to a range of 4.25% to 4.5%.

While the Fed can't do much to increase the supply of goods and services to ease pressure on prices, it can have an impact on inflation by lowering demand. By making it more expensive to borrow money, the Fed hopes to see spending and business growth slow down, which should in turn moderate price increases.

Inflation first started showing up as people shifted their spending during the pandemic from services to goods — and supply chains started buckling. Disruptions from the war in Ukraine has also contributed to higher energy and food costs. More recently, inflation has been moving more into services such as housing.

Adapting

Kashkari notes that his own family's consumption habits have changed because of the pandemic and high inflation.

His family used to get restaurant food delivered once or twice a week through DoorDash. Dismayed at how much they were paying, they've now cut that out.

He went to Lowe's and bought a small freezer to put in the basement. He fills it with frozen foods he buys in bulk during occasional stocking-up trips to Costco.

"My ability to adjust my shopping in the face of high inflation is a luxury I have that many people don't," he said.

For families who are already buying in bulk or already buying the store brands, they don't have many other options to switch, he said, adding, "So now what do you do?"

His regular shopping trips have also been a window into supply-chain issues. Earlier in the pandemic, he was keenly aware when his favorite Cherry Coke Zero was in short supply, leading him drive all over the Twin Cities to find it.

He's also noticed the smaller packaging that some companies have been using, commonly referred to as "shrinkflation."

Kashkari picks up a small tray of ready-made meatloaf as an example.

"It used to be a much deeper tray," he says. "So that's another way you're also seeing inflation as companies have shrunk the size."

As he usually does, Kashkari has brought one of his children with him on this recent shopping trip. Gripping a yellow toy car in one hand, his son, 2-year-old Tecumseh, happily chatters away in the shopping cart, occasionally asking his father to stop to grab a treat such as a snowman-shaped cookie.

As his cart fills up with groceries for the week as well as some household items such as garbage bags, Kashkari predicts it will be a big total at the end.

He's right. It rings up to $375.

UnitedHealth sues the Guardian, alleging defamation in coverage of nursing home care

Prices for international flights drop as major airlines navigate choppy economic climate

Minnesota's med spa industry rises in popularity — and with little regulation

Hundreds line up at Best Buy to nab Nintendo Switch 2, in scene like '90s opening parties