A county jail inmate lay in a padded restraint in a hallway, his head bleeding. A man sat in a wheelchair, weeping in the packed waiting room. Physicians at HCMC's emergency department debated whether a stabbing victim needed surgery.

A nurse cradled a phone, getting a handle on capacity: Of 23 ER patients needing admission to the hospital, only five had beds.

"That leaves 18 people without beds," the nurse said. "And 30 in triage, which will probably only get longer. Their longest wait back here is 24 hours."

Dr. Jim Miner, HCMC's chief of emergency medicine, ducked into the tiny physicians' break room. Here, away from scenes of chaos and desperation, he could take a breath. This was the height of summer, known here as "trauma season." For the past several years, Minnesota's busiest ER has hardly gotten a break: COVID and overdoses and gun violence and more, society's problems all funneling here. Layered on top of it all has been a spike in abuse of health care workers, from frequent name-calling to serious violence, like a patient choking an HCMC ER physician this summer, putting him on disability leave.

"We've been in crisis mode since COVID started," Miner said. "There's just not enough people, and that leaves a lot of problems for emergency medicine to fix."

A culture of stoicism permeates any ER. Doctors, nurses and staff shrug off daily trauma and get back to work. But in recent years, masses of health care workers — at HCMC, across Minnesota and nationwide — have simply quit. Stoicism is part of the problem, Miner believes. The hospital is trying to change that, with psychologists wandering halls to see who needs help, a kind of workplace therapy.

A relentless cadence had been going for hours as the hot, smoky week led into a long Fourth of July weekend, always the busiest of the year. Haze from Canadian wildfires engulfed Minnesota. Patients arrived with respiratory problems. A police officer and two paramedics lingered in the stabilization room, the fluorescent-lit, four-bed nexus for the most dire patients that adjoins the street-side ambulance bay. Nearby, an older patient moaned. Down the hall was a sign: "CAUTION: High Risk Elopement Area" — a locked unit for psychiatric illnesses, chemical dependency, detox. It's usually full.

"How have things been?" an incoming physician asked.

"Crazy," Miner replied. "Six hours of putting fires out, way busier than normal."

By week's end, the ER had treated 18 gunshot wounds and 49 assaults. Ten motorcycle crashes, 45 car wrecks, a couple of fireworks injuries. More than 200 people for headaches, back pain or chest pain. All on top of regular stuff: Sore throats, dizziness, vomiting, fever.

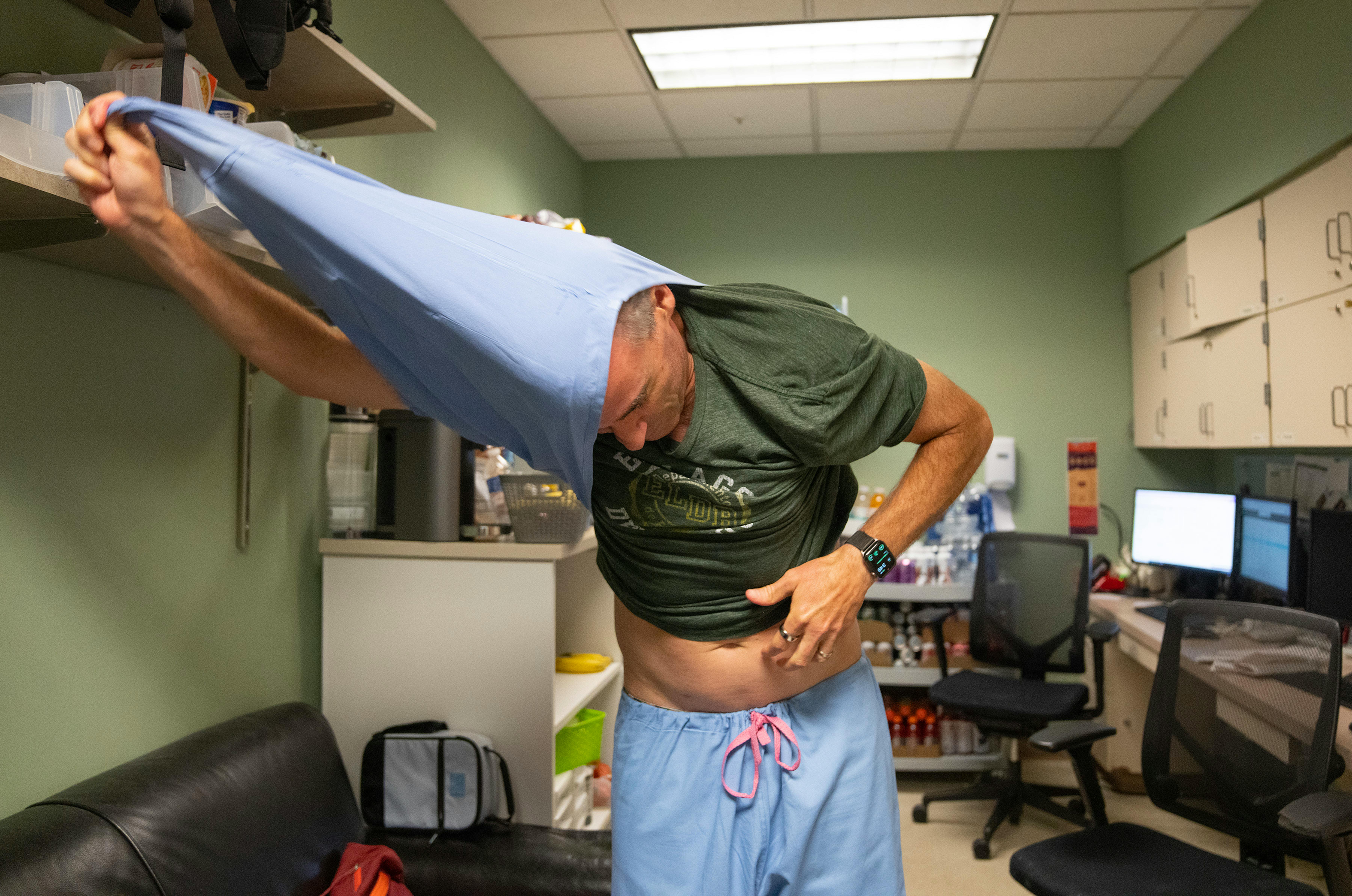

In the break room — barely bigger than a broom closet, with a couch, a miniature basketball hoop and a mountain of snacks and drinks — Miner squinted at an ultrasound image and typed notes. Then he pulled off his baby-blue scrubs, leaving the day's trauma behind. He had to take his golden doodle to the groomer. But he'd be back tomorrow.

All around us are signs of a community in distress. Nearly 15,000 Minnesotans have died of COVID. Minnesota opioid overdose deaths increased 43% from 2020 to 2021, with no signs of abating. An attendant mental health crisis overwhelmed an underfunded system.

Wildfire smoke chokes us, the sun bakes us. It can seem the world's coming apart.

For ER workers, no sign of societal distress is more distressing than gunshot wounds. Though gun violence is down this year, HCMC's emergency room has treated nearly one gunshot victim a day for the past three years.

The echo of 2020's racial reckoning lingers here, too: George Floyd was brought to this ER, and staff treated injuries during the riots. Many employees are married to cops, and the ER kept operating during former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin's trial in a tense, locked-down downtown.

"The biggest challenge is seeing where society has failed people and repeatedly trying to play catch-up to that," said Dr. Rochelle Zarzar, a physician here.

"You are the canary in the coal mine," said Dr. Thomas Wyatt, the department's senior medical director.

As spring turned to a scorching summer, staffers were on edge. Trauma season meant more of everything: Crashes on motorcycles, boats, ATVs, bicycles, scooters. Burns from fire pits, grills, fireworks. Drownings and heat exhaustion. Worst of all, gun violence.

They were also on edge about staffing. About 17% of Minnesota health care jobs remain vacant, according to a recent report by the Minnesota Hospital Association. HCMC's ER stood at two-thirds its full complement of 120 nurses in spring, with temporary travel nurses filling the gap. The grim finances of not-for-profit hospitals, which have lost hundreds of millions of dollars this year in Minnesota, combine with workforce problems to create what Dr. Rahul Koranne, head of the Minnesota Hospital Association, calls "an existential crisis — a worsening perfect storm."

As a safety-net hospital, HCMC never turns away patients, no matter their insurance, no matter their housing or financial situation, no matter how complex their issues. When mental health facilities are full, those patients come here. When other HCMC departments are full, those patients are boarded in the 30,000-square-foot ER, some staying a day or longer waiting for a bed. When the downtown Minneapolis ER's 66 beds are full, patients are treated in hallways.

The stressed-out staff's biggest worry is that this new normal becomes, well, normal.

One recent day, Wyatt began rounds at 3 p.m. In his section, 11 of 15 beds were filled by patients waiting to be admitted to other departments. Twenty more patients awaited hospital admission in other parts of the ER. Forty waited in triage.

"Part of the moral injury," Wyatt said, "is that we don't have the room, don't have the capacity. So no matter how hard I work, I feel like I'm not making a difference. People for years have talked about soldiers getting PTSD. There's a growing amount of evidence that people who work in environments like ours — police officers, firefighters, paramedics, emergency providers — can suffer that same type of thing."

"There has to be a strategy to cope with all this trauma."

"I treat this whole place like a trauma patient," said Mitch Radin, a Hennepin Healthcare clinical psychologist. "Patient after patient after patient is escalating your stress response, so your baseline for stress starts to get higher and higher and higher. After a while, the external world doesn't really match your sense of chaos. Work is the only place where you feel normal."

Before returning to his home state and reshaping HCMC's critical incident support team, which helps health care workers after traumatizing incidents, Radin counseled police officers and firefighters in San Francisco's Bay Area. Working with ER staffers, he said, is just like working with cops. They absorb stress but don't let it show. They know help is available but rarely reach out; it's hard to differentiate a truly overwhelming experience from daily work.

"It's people who look calm on the outside but inside are totally fragmented," Radin said. "They're like, 'There's something terribly wrong with me, because everyone else I look at looks totally calm. I'm the only one that is struggling here.' When in fact everyone is struggling here, but no one is talking about it."

Radin wants people to talk about it. HCMC's support team had been underutilized — file a form after a traumatizing event and a psychologist would reach out in a day or two. In the six months before Radin rebooted the team last year, a half-dozen staffers requested help.

Radin instituted a pager system where a psychologist would be available within 20 minutes. In the year since, the team has received 189 formal requests for support, plus informal "drive-by consults" in hallways. Radin's five-person team works alongside chaplains aiding both patients and employees.

This wasn't just improving workplace culture. This was survival, since health care workers are at disproportionate risk of suicide.

"I don't know anywhere else in the country doing it similarly to how we're doing it," Radin said.

But Radin doesn't want to act like field medics rushing to the newest trauma. He seeks culture change — a hospital-wide support group where informal therapy happens between colleagues during downtime, or in the quiet, somber moments after something truly awful.

Jenn Dreyer walked into a Starbucks near her Lakeville home a couple years ago, still thinking about her heartbreaking shift the evening before.

A boy, not yet a teenager, had been shot. An ambulance brought him to HCMC, where Dreyer has worked as an ER nurse for 12 years. Dreyer stood bedside in the stabilization room. The medical team opened the boy's chest to stanch the bleeding.

But the boy died. As Dreyer wiped blood from his body, the only noise piercing the silence was his mother outside the double doors, wailing.

Now here she was, in line at Starbucks, everybody happily living life barely 12 hours since Dreyer witnessed a child's violent death. This is the most unrelatable part of her job: How do you just go back to daily life after that?

Dreyer is no shrinking violet. She has a biohazard tattoo on her forearm and unwinds by watching "The Walking Dead." She's on a medical team that deploys nationwide after hurricanes and other emergencies. She's seen some stuff. Seeing stuff is one thing; that's the job. But feeling that society ignores the trauma right under its nose? That's another.

Outsiders can't understand why she signed up for this. Her husband, a former ER nurse, gets it. So do friends in law enforcement and the military. Dreyer sums up their mentality like this: "Some bad stuff happens, then the world goes on."

But Dreyer didn't sign up for abuse. There was a clear dividing line in 2020 when everything got worse: COVID isolation, overheated politics, a lack of empathy worsened by social media. "This can't be the only profession that feels like that, right?" she wondered. "People went crazy! Society kinda turned awful." Bad stuff, it seems, has become people's entertainment. She moved into a supervisory role to focus more on colleagues' well-being than patients'. Her Peloton classes became her therapy.

Yet there's no other profession she wants to do. So she looks for optimism. Instead of focusing on the horror of an old man attempting suicide, she tells of holding that man's hand as he died peacefully. She's traveling to Tanzania this winter to teach first aid to cops. She wants to help a broken world.

That morning at Starbucks, when her world felt especially broken, all this swirled in Dreyer's mind. Surely these people heard about the boy's shooting the night before. But it's just something they see on TV, Dreyer thought, not reality.

Dreyer ordered her coffee. Then she looked down. On her shoe was a spatter of the boy's blood.

"When you hear about it on the news," said Miner, the ER chief, "it's, 'These criminals were shooting at each other, and four of them ended up at HCMC.' The reality is, this was four lives that were just destroyed."

Miner's father was an Episcopal priest, perfect preparation for emergency medicine: Funerals, odd hours, comfort with death, an optimism things will get better. When Miner witnesses extreme human suffering, he focuses on the humanity.

"You see a lot of good in people when they are at their worst," he said. "You get some young person who has had a messed-up life and is involved in gang violence. But when they get shot, they're not a violent gang member. They're an 18-year-old boy, crying for their mom."

Miner finds healthy ways to cope: Exercise, cooking elaborate meals, playing bass in a rock band. Still, some days nearly break him.

"My worst day was last fall," he said. "Two teens were shot. One was dying. The other one was going to die. I took care of both of them. It was horrible. Just kids, you know? And I was on a phone call later. I'm an editor of this emergency medicine journal, on a call with a bunch of other editors. They were like, 'Jim, how's it going?' I go, 'I'm having a horrible day.'"

One colleague was from Canada — a fellow ER doctor in a county hospital.

"And he's like, 'I can't imagine what that's like,'" Miner recalled. "He'd never seen a patient killed by a gunshot wound before! It made me realize, so much of this is a society problem."

Sometimes bad luck sends people here. But Miner emphasizes how much is easily preventable: Seatbelts, helmets, fewer guns, avoiding drugs. Working here makes you equal parts jaded and paranoid: "It's a running joke in our house that I say, 'Wear your seatbelt and your steel-toed boots, bring your bubble wrap, wear your helmet, your mouth guard,'" Dreyer said. Miner loves music — Sublime, the Pixies — but he no longer goes to concerts, having seen so many overdoses.

He routinely participates in people's worst days, yet Miner stays optimistic. Zero nurse resignations in 2023 indicates staffing has stabilized. Those who remain are the truest believers, called to difficult, essential work.

"There's never any question what we do is important and makes a difference. I'm just tired. Exhausted. Overwhelmed," he said. "There's always going to be people who are left out when society moves forward, who have terrible problems, who need help. But when people are in these bad situations, they lose track of all the other stuff, and all they worry about is the people they love in their life. It's there in all of us. We just have to hang on and keep trying."