Etta Riley has learned to listen for a hiss when she hears pops erupt outside her Minneapolis townhouse.

The hiss brings relief. It means that bottle rockets are being fired in her neighborhood, not guns.

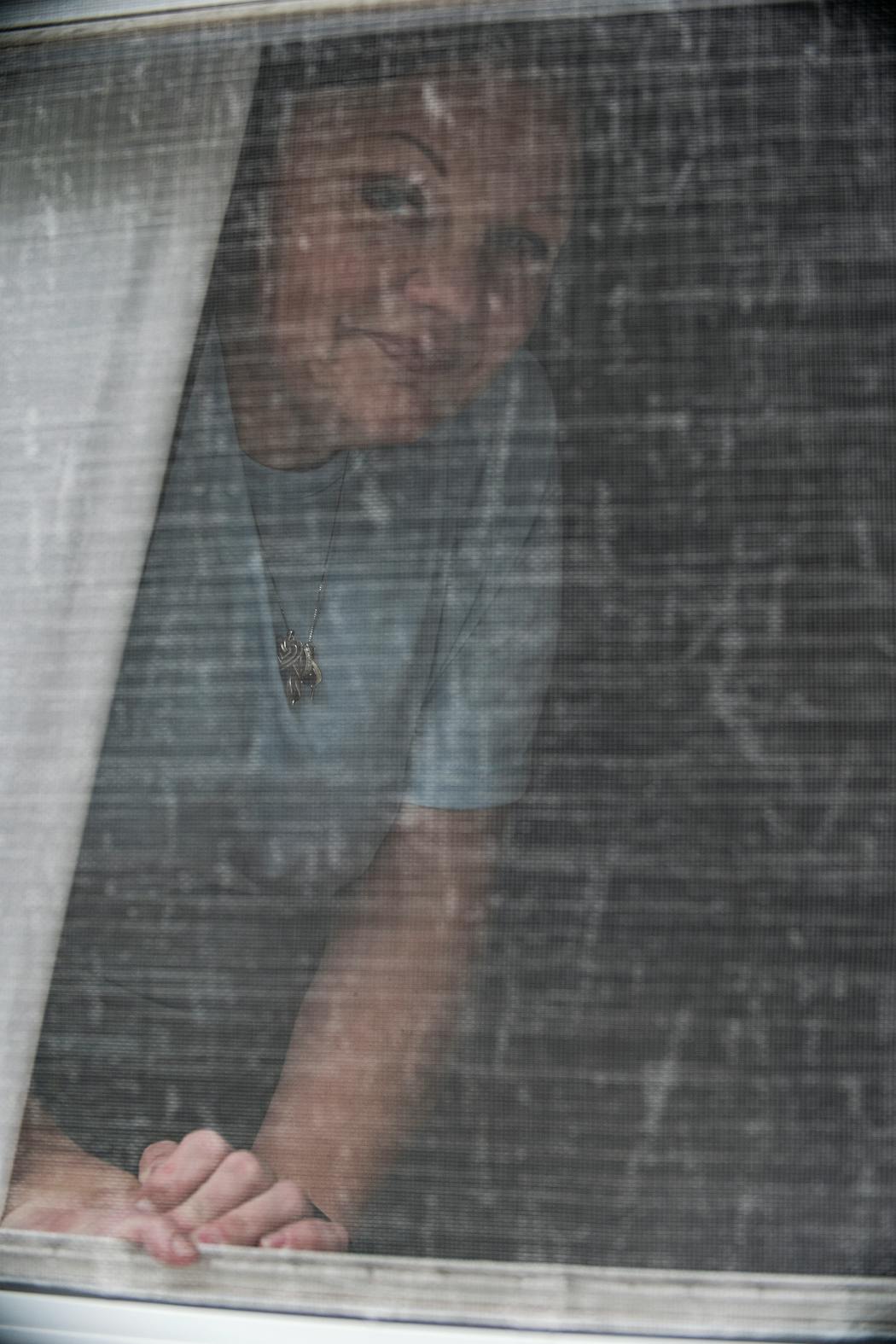

Riley, a 57-year-old school bus driver, remembers waiting for that reassuring sound one night in May. A group of strangers had gathered on a boulevard near her house — again — to throw dice, blast "cussing music" and drink from beer cans that would litter the street come morning. The gambling worried her. She has seen it lead to fights, which lead to guns. She called 911 and watched out the window as a police cruiser passed by and didn't even slow down.

Soon a crackle filled the air. This time, there was no hiss.

Riley stepped outside that night and watched police cordon off the nearby convenience store with yellow tape. She found out Aniya Allen, a kindergartner, had been shot there. She wonders if it would have made a difference if police had really shown up that night.

"There's just too much killing going on," Riley said.

Riley lives on a block of the North Side's Cleveland neighborhood that saw a 200% rise in gunfire compared with a dozen-year average before the pandemic. The dramatic surge in shots fired there and in other pockets of the city has brought a grim new reality for some residents across Minneapolis, who are now in the throes of what is shaping up to be overall the most violent two-year period in a generation.

After decades of declining violent crime, Minneapolis recorded 84 murders last year, up from about 48 in 2019, and a toll not seen since a dark chapter known as the "Murderapolis" years. The 67 murders so far in 2021 are on pace to surpass that. Four of those killings took place this week in a span of 29 hours, among them one with a 12-year-old victim. At least five kids 10 years old or younger have been caught in the crossfire this year, leading to news reports featuring images of picture-day smiles over descriptions of children on life support or inside tiny coffins.

The murder count represents only a small fraction of gun crimes. Data show a record number of gunshot wounds reported since last year. In the first six months of 2021, Minneapolis surpassed shots fired citywide in all of 2019, according to ShotSpotter activations, shooting reports and other data tracked by local law enforcement agencies. This year is on track to surpass 2020s record-high 9,600 gunfire reports. The past 20 months now account for almost a quarter of the 70,000 gunshot incidents reported in Minneapolis since 2008.

"You hear gunfire, it's like hearing birds chirping in the morning," said Juliee Oden, 55, who lives in the Jordan neighborhood, where shots have doubled. Oden's street has seen an even larger increase in gunfire. She has moved her bedroom from the front to the side of her house and acquired a steel plate to place behind her headboard in fear of being struck by the shots she hears at night. "I've listened to two situations where people have actually died," she said.

If not for the grisly news reports, many residents in Minneapolis may not have noticed the violence. Nearly 90% of the gunfire reports since 2020 came from five neighborhood clusters: Near North, Camden, Powderhorn, Phillips and Central. An analysis of gunfire incidents by census blocks further revealed how specific locations are driving up the citywide numbers. The Star Tribune interviewed dozens of people who live and work in these areas, which are by and large more ethnically and racially diverse, younger and lower income.

"It's never been like this," said Kia Banks, 42. Banks works in an assisted living home in the Folwell neighborhood, where shootings are up about 140%. Her clients love their community but feel unsafe walking outside in the afternoon. "I don't like to stay after dark and be driving around at night. I'm afraid of that."

A block away, a mother is selling her house, fearing her kids could be the next to get caught up in a hail of stray bullets.

"I just keep my kids away from the windows, and mainly I sit on my floor, because just in case, I don't want to be hit or have my kids hit," said the woman, who feared that her name appearing in this article would make her a target.

Shots rain down

Five miles south, in the Loring Park neighborhood, Kim Valentini has started locking the doors to her store even when it's open.

Living in this area for about 30 years, Valentini, 60, has seen it grow into a beautiful center of the city. A mix of new apartments and the ones built a century ago have made it one of Minneapolis' densest and most eclectic neighborhoods. That's why she chose Loring Park to open the retail arm of her charity, which provides oral surgeries for impoverished kids around the world.

But about 19 months ago, the neighborhood abruptly changed. "The bottom fell out," Valentini said.

Her business has been burglarized five times. Her car has been stolen twice. Her family wakes to gunshots in the night.

Gunfire reports in Valentini's neighborhood are up almost 400% through August compared with prepandemic averages, and the neighborhood's first homicides in years have put the small community on edge.

Shots fired in neighboring Stevens Square-Loring Heights are up about 200% from average. Adjacent Lowry Hill and Lowry Hill East, part of the Calhoun-Isles cluster, jumped from a combined average of nine gunshot reports through August each year to more than 60 in 2021. Violent crime is up in all four neighborhoods.

Valentini believes police want to help, but they're stretched too thin. At the same time violent crime is rising, police data show arrests for these offenses dropped by around one-third this year. "I feel guilty, frankly, about making calls to 911 about hearing shots fired," she said. "If there isn't imminent danger, I don't call."

Blocks away, Sam Turner, 40, has stopped serving dine-in customers at his 24-hour restaurant at night because gunfights, usually coming from a dice game across the street, have made the area more dangerous for staff and customers.

"They shoot straight up in the air, because they don't even realize those bullets land somewhere," Turner said.

Bullets have rained down on cars, the trees and facade in front of the Nicollet Diner and nearby apartments, in one case lodging into the drywall of a neighbor's bedroom, he said. "Hopefully the election comes and we get some politicians who give a crap about public safety," he said.

In a city election year, the blame is pointed in all directions. Some are searching for their own ways to better their situations.

Business owners meet and share tips from north Minneapolis preachers on how to disrupt violence. The nearby Wooddale Church hosts nighttime cookouts to draw out neighbors who badly need a hot meal and much more.

It's not only violence that lurks in these streets at night. The opioid crisis never loosened its grip. Heroin and meth are easy to find and cheaper than ever. And the pandemic has taken away badly needed social services.

"It's like a perfect storm of brokenness," said Wooddale Pastor Trent Palmberg.

'City of Wakes'

Those who have lived in Minneapolis long enough remember the only other time the city saw these levels of violence.

It started in 1985 with 16-year-old Christine Kreitz turning up dead at Martin Luther King Jr. Park. Kreitz belonged to the Black Gangster Disciple Nation, a Minneapolis faction of the Chicago Disciples. The gang's leader ordered her assassination after mistakenly suspecting she'd informed on him.

The murder marked a new era for Minneapolis crime. No one — not even the skeptical police chief who'd come from New York City — could any longer deny that Chicago gangs — real gangs — had arrived in Minneapolis.

The turf wars fed an unprecedented rise in killings in what had been one of the safest major cities in America, hitting the high-water mark in 1995 with 97 murders. The city held the 12th-highest homicide rate in the nation, passing New York City's. Residents made shirts that read "Murderapolis: City of Wakes," a moniker which the New York Times canonized in a front-page story about the downfall of a city "that seemed to have all the answers."

Then, for reasons still being debated, the crime rate plunged. By 2001, the murder count dropped to less than half of the mid-90s years. Violent crime has ebbed and flowed in years since, but it's continued to trend downward — until June 2020.

There are varying theories for what's driving the violence among those who live in the areas most affected: the Highs and Lows — gangs divided by north Minneapolis' geography — are beefing, and leaving a trail of bodies, sometimes the wrong ones, in their wake; the illegal gun market makes it too easy to find a firearm; and the pandemic left people out of work and home from school. There's also the movement to defund the police, which many in these areas believe is tied to the violence one way or another. Some say it is sending a message to good police that they are not wanted, driving hundreds to quit and leaving the remaining force too small to respond. Others believe police are retaliating against the movement by slowing productivity, showing how bad the city can get without them.

Riley sees the bad cops, like the ones who caught a man trying to rob the convenience store near her house, then continued to beat him after putting on the handcuffs. She thinks the ones who quit in response to calls for more accountability are "cowards." But she knows there are good ones too, the ones she's met in public meetings and sees patrolling her alley the next day, trying to help. She's known Charlie Adams, the Fourth Precinct inspector, since they were kids in the projects and everyone called him "Boobie." Today she calls Adams and his kids the "North Side Blue Bloods," after the Tom Selleck TV show about a multigenerational law enforcement family.

"If [police] do wrong, discipline them," said Riley. "I ain't saying defund them or get rid of them, because you know there are good cops. You can't punish the good ones for the bad ones."

Jordan neighborhood resident Dave Haddy, 48, says he supports reforming police, but he doesn't believe politicians have laid out a sufficient plan to replace the current model if the charter amendment to do so passes. "We need good police," Haddy said. "I'm sorry, but the people advocating [defunding police] the most don't live in these scenarios. Ask North Siders, at least the ones I talk to. They are not for abolition. They are for competent, just policing."

Danecha Gipson, 28, says the problems date back further than just last year, and the answer is more complicated than more uniforms on the streets. "We've got a lot going on that the communities have been sweeping under the rug for years," she said.

A few years ago, Gipson left her job as a nursing assistant to work for the Cleveland Neighborhood Association. She helped start programs that gave kids stipends in exchange for delivering groceries or doing chores for elders. But there aren't enough constructive opportunities to keep youth off the streets, especially during a pandemic, she said.

"These kids here are taking their hurt from home and taking it out on the community," she said.

'We look out for each other'

Tears spill down Julie Ward's cheeks when she thinks about Trinity Ottoson-Smith, the 9-year-old girl shot while jumping on a trampoline at a birthday party this year. Ward lives two blocks from the shooting site with her granddaughter Aubrey and heard the shots.

"That girl was the same age as [Aubrey]," said Ward, 66. "We have a trampoline. That vision, I just can't get it out of my head. If she got shot, oh, my God, it would kill me."

Aubrey skips across the street, her long braids bouncing with each stride, to where neighbors host an ice cream social on a humid evening in August. "I do want to move," said Aubrey. "I want to see what that feels like."

Her street is lush and dotted with character-rich homes, many well-maintained by their owners, interspersed with long-neglected and wilted ones. Some are recently vacant. Ward moved here in the late 1980s. One day she was in the backyard with her kids when two men darted through her property with guns akimbo. She's known since then her neighborhood has a dark side. But she fell in love with her house and her neighbors. Not until this year has she ever contemplated moving. "I'm scared," she said. "I don't want to go. But it's too close."

Ogi Carter hears the shots in her Folwell neighborhood, too. She woke up recently to someone firing slowly into the air from a moving car. The next morning she found shells in front of her home. "It shouldn't be like that," she said.

But Carter, 47, who immigrated from Bosnia, wishes people could see the North Side she sees. When a tornado hit in 2011, her neighbors helped remove a tree that landed on her house. Carter fell in love with the neighborhood then. "What makes it a community is really the people that live here," she said. "We look out for each other."

Haddy says the lack of concern for rising crime is emblematic of a difficult truth: Some people have always valued north Minneapolis less than the rest of the city.

"If any other neighborhood in this city had three children shot in the head in a span of three weeks, the National Guard would've been called out," he said. "But we didn't get [anything.] We get excuses and we get finger-pointing. And the people who say they are supporting us with all of their efforts, where are they?"

Outside Riley's house, the community built a memorial for Aniya Allen. "Rest in Heaven," reads one sign. Another shows Aniya and two other children killed this summer under the caption: "Do you know who shot me?" Police offered a $180,000 reward for that answer. The cases remain unsolved.

Riley sees the memorial every day. Politicians rallied here after Aniya's death, but now they don't come by. The raucous partyers have reclaimed the block to gamble.

"I just feel like we're the forgotten area," she said.

andy.mannix@startribune.com • 612-673-4036

jeff.hargarten@startribune.com • 612-673-4642