WASHINGTON – A Jan. 5 FBI memo that warned of armed extremists' plans to violently attack the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 never made it to the Capitol Police chief, a hearing Tuesday revealed.

The memo from the Norfolk, Va., office of the FBI stopped after it reached a sergeant in the Capitol Police office, former Chief Steven Sund told a joint hearing co-chaired by Sen. Amy Klobuchar.

The first public testimony from Capitol Police came during the first in a series of hearings examining what went wrong when thousands of supporters of former President Donald Trump breached the Capitol. The rioters threatened members of the Senate and House, including threats to hang Vice President Mike Pence and kill House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. The attack on the building resulted in five deaths, 140 injuries to police and property damage.

"These criminals came prepared for war," said Sund, who resigned under pressure following the Capitol breach. "I am sickened by what I witnessed that day."

Sund said he only learned of the report Monday. It detailed social media discussions calling for people attending a pro-Trump rally Jan. 6 to come armed and ready to fight as they tried to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election.

Some members of the Senate Rules and Homeland Security committees, as well as witnesses, questioned why the FBI sent the alarming report only as an e-mail instead of using more urgent channels. But several committee members remained incredulous that a suggestion of armed insurrection would not be forwarded by the Capitol Police intelligence unit to senior officials.

The fact that the Jan. 5 report "did not get to key leaders is very disturbing on both ends," said Klobuchar. "You can't just push send on an e-mail" and think it will end up in the right hands.

Yet even without the FBI memo, Sund, as well as former sergeants-at-arms for the House and Senate, said they knew members of white supremacist groups and other extremists might be coming to the Capitol and some would be armed. That still did not signal to them the need for a greater law enforcement presence.

The rioters' tactical awareness took police off guard. It resembled a well-organized military mission, witnesses said, including planting of pipe bombs at the Republican and Democratic national headquarters to draw police away from the Capitol.

Klobuchar said the testimony clearly indicated a "planned insurrection" replete with details that made it "highly dangerous." The Minnesota Democrat said the toll "could have been worse."

The nearly four-hour hearing also focused on police tactics to protect the Capitol against future attack. Some suggested more use-of-force training and better riot equipment for the Capitol Police, many of whom fought without helmets or armor and were beaten with clubs and sticks.

Among the most debated questions was how to deploy the National Guard. Currently, the Capitol Police chief must ask for permission from a police review board to request the National Guard.

The timing of that request led to conflicting testimony between Sund and former House Sergeant-at-Arms Paul Irving, a police review board member. Sund said he called Irving asking for permission to summon the National Guard at 1:09 p.m. on Jan. 6 as the mob moved across the Capitol lawn. Irving testified he had no recollection of or record of the call. Irving said when Sund reached him at 1:28 p.m., the police chief said only that he was thinking about calling the National Guard.

When police officials finally reached out to the Guard at 2:22 p.m., about the time police evacuated members of the Senate and House chambers to protect them from the invading mob, Army officials balked, said Robert Contee III, acting police chief of the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Police.

"I was stunned at the response from the Department of the Army, which was reluctant to send the D.C. National Guard to the Capitol," Contee testified. "While I certainly understand the importance of both planning and public perception — the factors cited by the staff on the call — these issues become secondary when you are watching your employees, vastly outnumbered by a mob, being physically assaulted."

By the time the Guard arrived, the riot had been brought under control. But injuries, deaths and property damage had already occurred. Democratic Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia said the situation called for giving the D.C. mayor power to call out the National Guard.

Warner, now chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, also said the government must pay more attention than Trump did to extremist groups like those that helped lead the Capitol riot. Trump's critics accuse him of empowering racist and anti-government groups.

"This is an ongoing threat to national security," Warner said. "I fear it did not get the attention it deserved in the former administration."

Republican Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, who has repeatedly questioned whether the riot was an armed insurrection, read from a lengthy article on the conservative site the Federalist written by J. Michael Waller, an analyst at the Center for Security Policy, a right-wing think tank. Waller's account of the beginnings of the riot claimed there were "fake Trump supporters" and "agents-provocateurs" in the crowd, and appeared to place blame for the violence on Capitol Police who fired tear gas in a futile effort to stop the rioters from breaching the building.

"The tear gas changed the crowd's demeanor," Johnson said, quoting Waller. "There was an air of disbelief as people realized that the police whom they supported were firing on them."

Johnson did not give security officials a chance to respond to the widely debunked claims that the rioters in Trump regalia who attacked the Capitol after a Trump rally weren't Trump supporters.

The final question that provoked discussion was how to secure the Capitol going forward. Republican Sen. Rick Scott of Florida questioned the continued need for fencing, as well as the continued deployment of the National Guard.

Contee said he was "not sure we need razor wire around the Capitol."

Klobuchar and others urged solutions that make the Capitol safe, but publicly accessible.

One thing that seemed inevitable based on the testimony, Klobuchar said, is that affixing blame was less important than fixing the problems.

"You can point fingers," she said, "but we were not prepared."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Jim Spencer • 202-662-7432

JD Vance, an unlikely friendship and why it ended

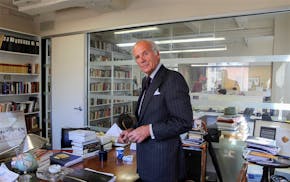

Lewis Lapham, editor who revived Harper's magazine, dies at 89

Body of missing Minnesota hiker recovered in Beartooth Mountains of Montana

Mike Lindell and the other voting machine conspiracy theorists are still at it