What Minnesota inventions have shaped modern life?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Pacemakers, Post-it notes and Spam rank among the state's best-known inventions. But creative Minnesotans devised hundreds of other products we take for granted, including modern seatbelts, Nerf footballs and water skis.

Sharon Carlson asked the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project, Curious Minnesota, to outline Minnesota's notable inventors and their creations.

"Minnesota is really a great source of invention over the last century," said patent attorney Benjamin Edlavitch, president of the Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame, a nonprofit organization. "The 'why' is probably the large corporate presence and the large academic presence in this state. Specifically, it's hard to say. Maybe it's something in the lakes."

John Banovetz, chief technology officer at 3M, said there's a lot of cross-pollination among the many different industries, universities and colleges that call Minnesota home. That's important, because "innovation happens at the interfaces of different disciplines," he said.

What follows is by no means a comprehensive list or a ranking. Books can be (and in some cases have been) written on these and other Minnesota innovations. Some inventions were excluded to highlight lesser-known Minnesota innovations.

Would you like to see an entire story written about one of these inventions? Did we miss a notable one? Send us a note at curious@startribune.com.

Pop-up toasters

Alan MacMasters invented the first electric toaster in Scotland in 1893. But it was a Minnesotan who added the pop-up feature now essential for browning — and not burning — bread.

While working for a manufacturer in Stillwater, Charles P. Strite grew tired of the blackened toast he ate for lunch in the cafeteria. So in 1921 he developed the Toastmaster, which used a timer and spring to turn off the heating element and eject the bread.

"Strite's invention found its way into restaurants immediately," Hennepin History Museum curator Alyssa Thiede recounted in a 2018 article. "By 1926, he introduced a consumer version with a variable timer that allowed the user to adjust the desired lightness or darkness of their toast."

That basic design is still used in toasters today.

Retractable seat belts

A University of Minnesota professor made headlines in 1957 for purposely crashing a car, repeatedly, in the name of academic research.

"Stunt men won't crash cars," James J. "Crash" Ryan told the Minneapolis Tribune. "Nobody crashes a car into a barrier except me."

Through his head-on research, in 1963 Ryan patented the first automatic, self-retractable seat belt that tightens on impact — now standard-issue in autos worldwide. (Earlier, he also created the first iteration of a "black box," an airplane's crash-survivable audio recorder that all commercial aircraft are required to carry.)

Frozen pizza

There were other frozen pizzas that came before, but let's hand it to Rose Totino for making Minnesota a champion of home-baked 'za and moving past what she called the "cardboard crust" that was the industry standard.

"She was the inventor of the first pizza dough suitable for freezing and subsequent baking," reads Totino's entry in the Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame. "She was an innovator and entrepreneur who helped to introduce frozen pizza to America, and later improved the product."

In 1962, Rose Totino and her husband, Jim, went from running a thriving Minneapolis pizzeria to a manufacturing plant in St. Louis Park that mass produced and nationally distributed frozen pizzas. Totino eventually sold what was the second-best-selling frozen pizza brand in the country to Pillsbury in 1975, and it is today a billion-dollar brand for General Mills.

Refrigerated trucks

Frozen pizza couldn't have traveled far without Frederick McKinley Jones. Minneapolis businessman Joseph Numero asked Jones to develop mechanical refrigeration for trucks in 1938 — which helped established Thermo King.

"Used in trucks, railroad cars, ships and planes, Jones' technology revolutionized the distribution of food and other perishables," says Jones' National Inventors Hall of Fame biography. "It made fresh produce available anywhere in the country year-round, changing Americans' eating habits."

Jones would earn dozens more patents and become chief engineer and vice president at Thermo King, which today has billions in sales annually. In 1991, he posthumously became the first Black American awarded the Medal of Technology.

Scotch tape

Tape in its modern sense was first patented in Britain in the 19th century. But the stuff that doesn't leave goo behind or take paint with it came out of Minnesota in the Roaring '20s.

Automakers dealing with the popularity of two-toned cars needed a tape that wouldn't damage paint. St. Paul native Richard Drew, then a 23-year-old lab assistant at a little abrasives company called 3M, said he could find a way. And he did, mixing cabinetmakers glue and glycerin on the back of crepe paper to make Scotch masking tape in 1925. Drew also led the development of the world's first waterproof cellulose tape — Scotch transparent tape, which came out in 1930. Millions of miles of it have been produced in Hutchinson, Minn., in the decades since.

As for the "Scotch" brand, a 2019 article in Smithsonian Magazine explained that Drew's first attempt at the tape was not so successful: "When the painters used it, it fell off. They allegedly told Drew to take his 'Scotch' tape back to the drawing board, using the term to mean 'cheap,' a derogatory dig at stereotypical Scottish thriftiness." The company embraced the moniker and uses it on a wide range of products.

Scotchgard

3M is also a major contributor to the proliferation of PFAS, aka "forever chemicals." These were first commercially popularized in Scotchgard, a water- and stain-resistant fabric treatment invented in 1952. It was discovered accidentally by Patsy Sherman after fluorochemical rubber was mistakenly spilled on an assistant's tennis shoe, according to the Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame.

With chemical bonds nearly impossible to break — hence why they take so long to break down — PFAS have proven useful in nearly every aspect of modern life, like grease-proofing food containers, waterproofing rain jackets and preventing food from sticking to cookware. These benefits have come at a high price to the environment and human health, however.

3M is ending its manufacture of PFAS chemicals by the end of 2025. Scotchgard no longer uses PFAS.

Nerf footballs

Backyard football players have a Minnesota Vikings kicker to thank for the squishy Nerf football, invented in 1972.

Fred Cox and John Mattox asked a Minneapolis injection molder to make a foam football about three-fourths the size of regulation balls and took the product to Parker Brothers. The company had begun producing round Nerf balls a few years earlier — the invention of another Minnesotan, Reyn Guyer.

"[Parker Brothers] had been trying to make a Nerf football for three years," Cox told Vikings.com before his death in 2019. "They were trying to make them the same way as their round balls, taking a block of foam and using a hot wire to cut balls out of the foam. Their footballs had holes in them. They had tried everything except for injection molding them. The man said, 'I want that ball.'"

Rollerblades

Inline skates first came along in the 1700s in Belgium, but they were largely forgotten. The two-by-two roller skate design was patented during the Civil War.

It was Minneapolis that gave the world capital "R" Rollerblades in 1980. Scott Olson, then just a teenager, put polyurethane wheels and a rubber heel brake on a blade-less hockey skate.

"I lived on the ice in the wintertime, and I dreamed about being able to ice-skate for transportation," Scott Olson told the Star Tribune in 1985. "I thought it would be just something to be able to skate to school every day."

Olson skated around the city, and the state, to pitch the product. He and his brother, Brennan, ran the company from their parents' basement before it was sold in 1984. Rollerblading then really took off with the help of some heavy marketing investments.

Reflective road signs

From 1922 to 1954, stop signs in the United States were yellow. Red was the preferred color, but dyes at the time faded too easily. An innovation from 3M transformed the look of America's roadways.

"Red was made possible with our reflective sheeting," staff at 3M's Innovation Center explained in an email. "Initially we did this using glass beads, which retroreflect light back to the source, so a driver can see a sign earlier."

Harry Heltzer first developed a reflective tape with glass beads in the 1930s. In 1939, the first traffic sign using the material, Scotchlite, went up in Minneapolis. Heltzer would go on to be CEO of 3M from 1970-1975.

Pontoons

Lake lovers of Minnesota and beyond have Ambrose Weeres to thank for the flat-decked boats on tubes. The farmer from Stearns County assembled the first pontoon, later dubbed The Empress, in 1952.

The first models were rudimentary — Weeres welded oil drums together for his prototype — but they answered an obvious consumer demand:

"Wouldn't it be nice if you could build a boat big and stable enough so you didn't have to keep telling the kids to sit down?" Weeres once recalled, according to his Star Tribune obituary.

Water skis

Ralph Wilford Samuelson was 18 years old when he became the first person to water ski — behind a boat on Lake Pepin — in 1922.

But it took 40 years for the world to recognize him as "the father of water skiing" after a Pioneer Press editor found that Samuelson's feat predated a New Yorker's long-held claim by several years.

"Had I realized what I had started, perhaps I would immediately have patented my skis — gotten some sort of publicity, had myself photographed by sports magazines, perhaps had cards printed calling myself 'The Inventor of Water Skiing' — cashed in somehow," Samuelson told the paper in 1965. "Fact is, I was stupid about the significance of what I had done."

Lake City unveiled a statute of the hometown inventor in 2022 to commemorate the centennial of Samuelson's invention.

Twister

The Associated Press began its 2013 obituary for Chuck Foley like so: "Twister called itself 'the game that ties you up in knots.' Its detractors called it 'sex in a box.'"

Foley and collaborator Neil Rabens created the iconic game in the 1960s for a St. Paul company.

"Dad wanted to create a game that could light up a party," his son, Mark, said in the AP obituary. "They originally called it 'Pretzel.' But they sold it to Milton Bradley, which came up with the Twister name."

Zubaz

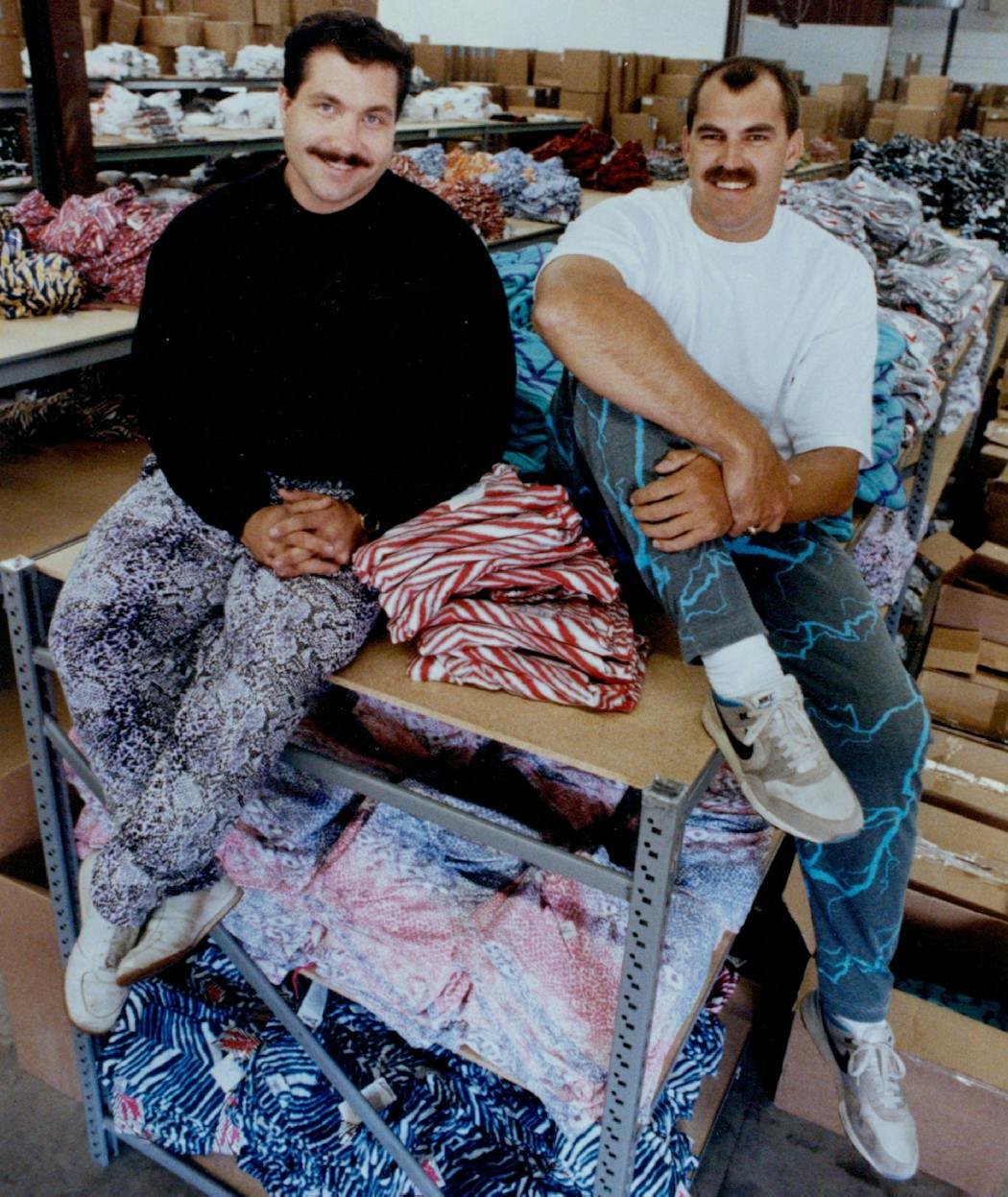

Bob Truax and Dan Stock were in search of something baggy enough to fit the bulky bodybuilders who came to their gym in Roseville, so they decided to start making their own pants. It just happened that zebra stripes were the most popular design they stitched up.

Zubaz, those baggy, bright and striped pants were invented in 1988 and quickly became a hit. But just as quickly, they faded into a bygone fad.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why did Spam become an international sensation?

The Jolly Green Giant has moved on from Minnesota. So who is maintaining his iconic billboard?

Why are Honeycrisp apples still so expensive?

How did Tonka trucks get their start in Minnesota?

Why a slice of I-94 west of the Twin Cities is a 'candyland for researchers'

What was the first movie filmed in Minnesota?

Correction: Previous versions of this article gave incorrect credit for the invention of the round Nerf ball. It was invented by Minnesotan Reyn Guyer.