Is it true that Minneapolis has a park every six blocks?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

It is hard to walk far in Minneapolis without stumbling across a public park. That's one reason why the city's park system is nationally acclaimed.

But is it true that every city resident is within six blocks of a park? An anonymous reader posed that question to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by great questions from inquisitive readers.

The six-block claim is trumpeted by guidebooks and the city's tourism bureau. Ensuring residents are within six blocks of a park is even one of the guiding tenets of the Park Board's last comprehensive plan, written in 2007.

And it is generally true — with some exceptions. Ninety-eight percent of Minneapolis residents live within a half mile of a park, according to data collected by the Trust for Public Land (TPL), which analyzes park systems across the country. Park Board officials said that is roughly equivalent to six blocks.

TPL recently named Minneapolis the nation's top park system for 2020, a title the city has received several times in the past. The San Francisco-based nonprofit scores cities based on a number of metrics, including the percent of residents within a 10-minute walk (half a mile) of a park, the acreage of city parkland, spending on parks and amenities at parks.

Minneapolis has some stiff competition across the river, however. St. Paul, which TPL ranked third overall this year, can boast that 99% of its residents live within a half-mile of a park. Minneapolis ranked higher largely because its parks, on average, are bigger.

Adam Arvidson, director of strategic planning for the Park Board, said TPLs analysis helps them understand where there are gaps in the system. It's partly why the agency purchased what's known as the "CEPRO site" for a park off Midtown Greenway, for example, in an area that had been identified as underserved by parks.

Other places they are planning expansions are transitioning industrial areas like the North Loop and Southeast Como, as well as near Crystal Lake Cemetery in north Minneapolis.

"In almost every area where there is an identified gap, we either have existing policy direction or are actively working on providing more parkland to the public," Arvidson said. "This Trust for Public Land analysis has been very helpful to us in understanding exactly where those gaps are."

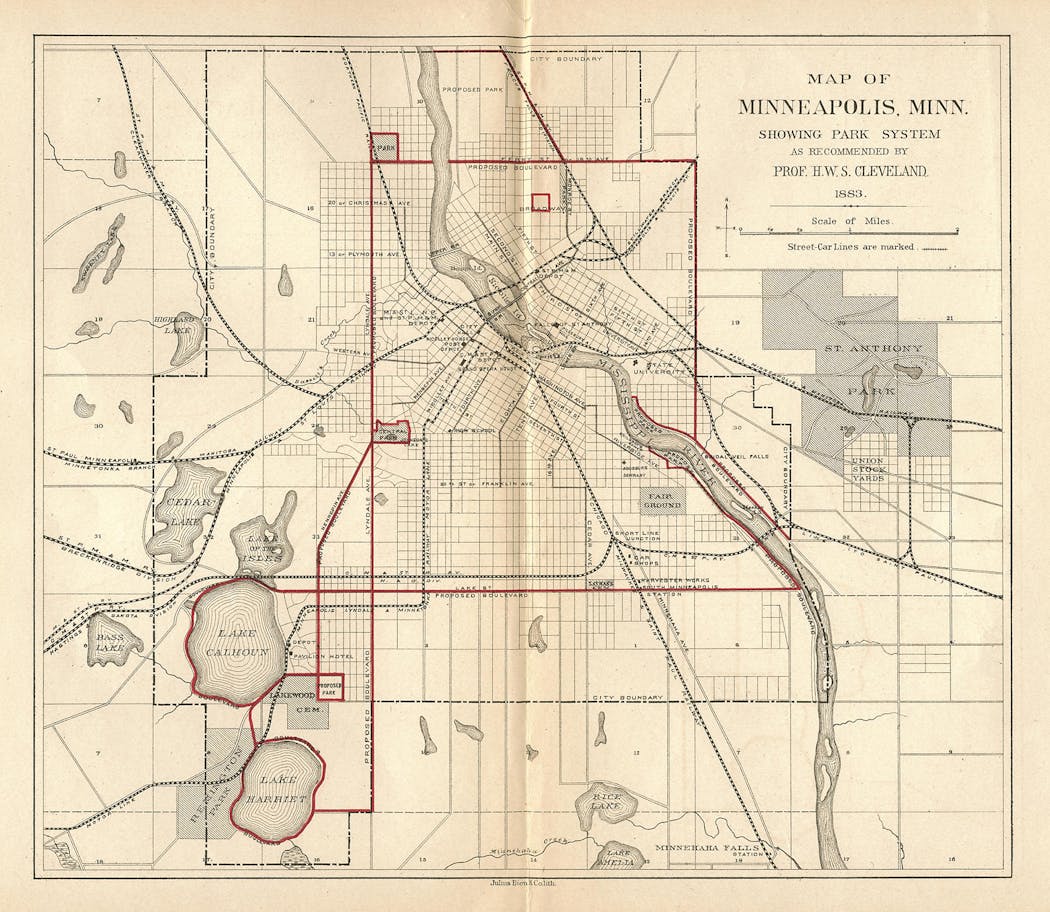

The proliferation of parks in Minneapolis today is partly due to the city's historical focus on developing parkland.

"If you have faith in the future greatness of your city, do not shrink from securing — while you may — such areas as will be adequate to the wants of the city," landscape architect Horace Cleveland told park commissioners in 1883, the year the Park Board was established.

"Look forward for a century, to the time when the city has a population of a million, and think what will be their wants," he continued. "They will have wealth enough to purchase all that money can buy, but all their wealth cannot purchase a lost opportunity, or restore natural features of grandeur and beauty, which would then possess priceless value."

That early planning for parks before the city grew is one reason why Minneapolis has a "superb" system, said University of Manitoba landscape architecture professor Alan Tate, author of the book "Great City Parks."

"Most cities expand and then go, 'Oops we need a park.' Whereas [Minneapolis] worked the other way around," Tate said.

Tate said Minneapolis' system is also unique for having a directly elected Park Board with a steady stream of tax dollars dedicated specifically to parks.

"There are two or three places across the country that have a system like that," Tate said.

David Smith, who wrote a history of Minneapolis park system, said the goal of having parks within a half-mile or six blocks of city residents likely dates back to the 1910s. There was growing acceptance at the time that parks were a place for recreation, rather than just relaxation.

"It was kind of a national goal, which very few cities achieved," Smith said. "Minneapolis did, and all credit to them for doing that."

The city accelerated buying land for neighborhood parks and playgrounds after a 1914 study found the city was lacking in playground facilities. The Minneapolis Tribune reported in 1916 that the Park Board had plans for a playground "within a half-mile of every boy and girl in Minneapolis," which at the time required building 27 new playgrounds.

"From the earliest days there was a constant demand or request: Neighborhoods wanted parks," Smith said. "And once you established neighborhood parks ... every neighborhood wanted one."

---

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Listen: How did Minnesota become one of the most racially inequitable states?

Where does 'uff da' come from, and why do Minnesotans say it?

Why is Minnesota more liberal than its neighboring states?

When you flush a toilet in the Twin Cities, where does everything go?

Does Minnesota really have the worst winters in the country?

How did Minnesota's early settlers make it through the dark, cold winters?

Why do we have water towers and what do they do?

Why does the Stone Arch Bridge cross the river at such an odd angle?

How did Minnesota become the Gopher State?