The NIL revolution | A Star Tribune series examining how the name, image and likeness era is transforming college sports: startribune.com/nil.

. . .

Business hours were winding down on a Friday last month when Gophers administrator Jeremiah Carter broke into mad-scramble mode.

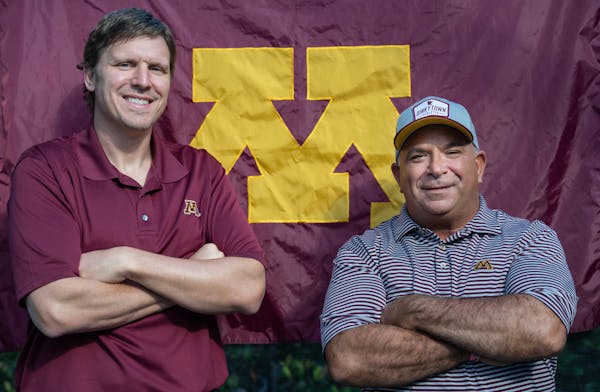

Carter's the point person at the U on everything and anything involving the name, image, and likeness (NIL) movement — a highly competitive facet of modern college sports, with athletes now paid based on their brand and schools battling for position.

Carter wasn't the only one scrambling on Feb. 23 after a federal judge ruled the NCAA could no longer stop NIL entities called collectives from offering money to recruits. That was a key development for Minnesota, rival schools such as Wisconsin and Iowa, and almost any member of Division I athletics.

"Working with NIL, you're never off the clock," said Carter, the Gophers senior associate athletic director for NIL/Policy and Risk Management.

The 43-year-old Carter, a 6-foot-6 former All-Big Ten lineman, suddenly had information that needed gathering, deciphering and spreading to the Gophers collective, coaches and his fellow administrators.

"The first thing to figure out was, 'What are the immediate issues we were going to see and how we respond?' " said Carter, who immediately phoned Gophers Athletics Director Mark Coyle on what stance the U should take.

Not long after talking with his boss, Carter connected with the only person who directly reports to him, specifically on NIL matters within the athletic department, Kiara Buford.

The NIL revolution keeps changing, sometimes daily, and Carter and Buford are a dynamic duo tasked with making sense of everything and finding ways to help the Gophers keep up. Carter acts as a crucial middleman between U leadership and the collective Dinkytown Athletes, which acts as a conduit for athletes and endorsement opportunities. Working with athletes is what Buford does best.

"I've tried to absorb as much as possible to stay up to date," said Buford, a former Gophers basketball player who was hired in November as director of alumni relations/NIL. "Jeremiah's been super supportive in teaching me things to be able to learn just as fast as NIL is evolving."

Trusting a former teammate

The Feb. 23 ruling wasn't a bad thing from the athletes' perspective, and some collectives reportedly had already been offering money to recruits.

A big step for Carter was communicating with former Gophers football teammate Derek Burns, co-founder of Dinkytown Athletes, which sets up NIL opportunities for current U athletes.

At first, Carter told Burns to hold off interacting with recruits until the Gophers grasped the situation. By early March, Dinkytown Athletes got the U's blessing to be involved in the recruiting process based on what's allowed.

"I don't view the injunction as a bad thing right now," Carter said, adding that Dinkytown Athletes has the resources to be competitive with a lot of programs in recruiting.

Coaches aren't allowed to have direct conversations with the collective, so Carter worked with the compliance office to inform Gophers head coaches about the new rules and how to communicate to recruits about the process.

"I'm incredibly grateful for Jeremiah Carter," said Coyle, who in March 2022 moved Carter from another key role as the Gophers' NCAA compliance director to the lead NIL position.

Carter said all Big Ten programs now have a full-time NIL point person in athletics like him, but not many are also on the senior staff. "That's a little bit unique here," Carter added.

A Pennsylvania native, Carter is the son of a longtime college administrator. He has seen sports from different lenses: player, coach and administrator.

Carter's father, Carlyle, broke diversity barriers as the first commissioner of the MIAC, which made him the first person of color to head an NCAA conference that didn't include historically Black colleges.

Carter worked in the NCAA's academic affairs for six years before returning to the U in 2013. He never imagined partnering with Burns in such a critical area for the Gophers' success.

"We hadn't seen each other for 15 years, but you instantly fall back into a rhythm," Carter said. "In the opening days of the NIL and the collective, it required a lot of trust from both parties."

The myriad challenges since NIL was approved by the NCAA in 2021 made Carter an ideal candidate to guide the Gophers, Burns said.

The Gophers, through Carter, are constantly in contact with Burns and Dinkytown Athletes co-founder Robert Gag on, for example, which football, basketball, or hockey players are best candidates for top NIL deals. A major priority is keeping the top athletes from leaving via the transfer portal.

"He helps us understand where the priorities are," Burns said. "Then it's up to us to put together some of these [bigger NIL] contracts in order to help support the players who are currently there.''

Guiding Gophers

Buford can't help but wonder, if she were playing today how much she could've maximized NIL opportunities as a hometown standout.

"It's just a different ball game now," said Buford who won back-to-back high school state basketball titles and was a two-time Gophers MVP and part-time model in college. "I think about what it could've been for us," she added.

Now she's making sure the next Kiara Buford can fulfill her NIL potential. Some of the U's most high-profile athletes are women, including Gophers basketball leading scorer Mara Braun and all-league gymnast Mya Hooten.

"It really opens the door for female athletes," said Buford, who previously coached Robbinsdale Cooper to its first state title in 2018. "That's an area where we can continue to grow."

The Gophers hired Buford in November to lead Gophers alumni relations and guide student-athletes on NIL participation and branding. "She's done a great job building something from scratch," Carter said.

Carter and Buford graduated from St. Paul Central a decade apart, and now they have offices steps apart in the U's Athletes Village. Buford does more of the interacting with athletes and their day-to-day NIL needs, especially on how to handle social media.

"Once a brand or company sees you get a lot of attention," Buford said, "they'll want you."

Braun, Hooten or other stars like Dawson Garcia in hoops or Darius Taylor in football have access to national NIL platforms, and Buford studies other schools to figure out how the U's resources can grow with athlete branding.

Social media connects athletes to businesses that can help them profit from NIL, but the noise can be hard on their mental health, Buford said. She teaches them how to manage the spotlight.

"That's the part we try to navigate how much time they put into NIL," she said. "Being a college athlete is hard enough."

. . .

The NIL revolution: Please read previous installments of this series at startribune.com/nil.

Souhan: Twins wait to see if end of a slump you'd never expect is salve for an injury you'd never anticipate

Twins find fuel in back-to-back homers, defeat Blue Jays

Lynx overwhelm pesky Wings in the fourth quarter, improve to 9-0

Twins lose Matthews to injury; Woods Richardson likely to join rotation