With a veteran's eye, Justin Jefferson immediately spots the mistake in a rare lowlight from his first two NFL seasons.

Sitting in the equipment room at TCO Performance Center last month, the Vikings' 23-year-old superstar receiver watches on a smartphone as a third-down pass falls to the turf with All-Pro cornerback Jalen Ramsey defending in a loss to the Rams last season.

Jefferson points at the screen when his knees briefly stutter and his head ducks in front of Ramsey about 5 yards downfield.

"This is really my fault," Jefferson says. "I'm knee stuttering too early, allows him to not bite on it as much. You see how he bit on it? But he had time to really recover because I did it so early. If I would've did it more at like 8 to 9 to 10 yards [downfield], he probably would've stuttered, and I probably would've got by him."

Self-critique precedes growth, and no receiver in NFL history has grown as quickly as Jefferson, whose 3,016 receiving yards are the most by any player in his first two seasons. Watching all 292 passes thrown his way, charting every route and interviewing teammates, coaches, analysts and Jefferson himself reveal the anatomy of an all-time great in the making: a football brain beyond his years, natural body control, keen eyes paired with precise footwork, and sticky hands that cap abnormally long arms.

Jefferson dominates on nearly any route from any alignment in the offense. More than two-thirds of his record-setting yards have come as an outside receiver, evaporating pre-draft concerns that he was used only in the slot at Louisiana State. He escaped that pigeonhole, which contributed to his being the fifth receiver drafted in 2020 at 22nd overall, and has flown to the top of the NFL, with All-Pro cornerbacks following him.

Being shadowed by Ramsey told Jefferson he was one of the best. Now he wants to be the best.

"You can tell his mental part of his game is growing, confidence is growing," Vikings cornerback Patrick Peterson said. "He got everything working in his favor right now. You can just tell he's extremely focused on being the best receiver in the game."

Football intelligence

Peterson still remembers a younger Jefferson's impressive grabs at the West Campus Apartments parking lot in Baton Rouge, La., next to Tiger Stadium. Jefferson wasn't yet a teenager when he was playing backyard ball with his older brother Jordan Jefferson, an LSU quarterback, and Peterson, Jordan's college teammate.

Justin was often nearby when Jordan reviewed Tigers game footage, pulling out discs that taught both Jefferson brothers about defensive coverages.

"It was a lot of tapes," Justin said.

Playbook schooling from a quarterback's perspective set Jefferson on a rocketing trajectory, further boosted by sitting next to receiver Adam Thielen in the Vikings' film room. Coaches say Thielen and Jefferson, who is nine years younger, frequently discuss strengths and weaknesses of individual defenders and coverages, allowing each to maximize every route.

"[Jefferson] understands leverage pretty well," safety Harrison Smith said. "Where to fit into windows and things like that, how to work [defenders] at the top of routes. You don't always see that this early in a guy's career."

Processing opponents before the snap helps Jefferson be one of the NFL's top deep threats. Defenders point to his work "at the top of the route," or before he declares his direction downfield. As he runs straight ahead, Jefferson disguises intentions with minimal extra motion in his arms and feet before breaking left, right or back toward the quarterback. He can also fake out a defender with a false step and head fake called a rocker step.

He gave one to Bears safety Deon Bush on a corner route for a 12-yard touchdown in last year's win at Chicago.

"That also plays into his high level of football intelligence," said Matt Bowen, ESPN analyst and former NFL safety. "Knowing when he's going to plant that outside step, knowing when he's going to set up a defensive back to go where he wants to go and understanding what the coverage is telling you."

Four deep routes of 20 yards or more — post, corner, post-corner and go routes — account for nearly one-third of Jefferson's yardage and eight of his 17 touchdowns. He tied Seattle's Tyler Lockett last season with the most targets at least 20 yards downfield, per Pro Football Focus.

In Baltimore last year, Jefferson's 50-yard touchdown on a post route started before the snap. He saw a Ravens defender turn around and signal a teammate on third-and-7. Without slowing, Jefferson faked a step outside to throw off the defender and cut back inside. The runway was set.

"I seen them talking," Jefferson said. "He was like, 'Watch the outside-breaking route.' So, I gave him a one-two step to the outside and seen the safety come down to K.J. [Osborn], and I'm like, 'Oh yeah, Kirk [Cousins] has to throw this.' "

Natural body control

On a field at a training facility outside Miami last summer, Vikings receiver Bisi Johnson knew he was witnessing the abnormal. Johnson watched Jefferson bend and weave through routes like water.

"Just the way his body moves is actually different," Johnson said. "The way he can cut, and the way he can get in and out of breaks, it's tremendous. It's different. I don't know how else to describe it. It's things he can do that other people can't."

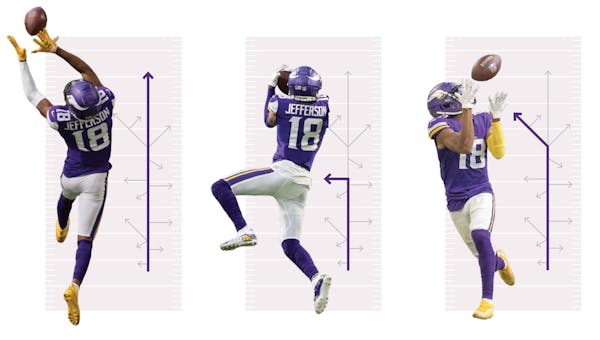

Impeccable body control is a born talent, according to Jefferson, who can twist midair to pluck away passes with 33-inch arms rivaled by few other 6-1 receivers.

Skyward contortions give quarterback Kirk Cousins a reliable landing spot for lobbed passes on fade and go routes. Jefferson has come down with 16 catches for 495 yards and three scores on those routes, including a 27-yard grab against the Chargers last season.

The pre-snap read wasn't good for Jefferson on that play. He was supposed to run a stop-and-go route down the sideline, but Chargers corner Tevaughn Campbell was leaning toward the sideline. Jefferson said he improvised, stuttering only briefly before accelerating to beat him downfield. Campbell was still in Jefferson's hip pocket, forcing him to make a twisting, contested grab.

"The football is kind of on the back shoulder," Bowen said. "His ability to track the ball, the body control but also the competitiveness to go up and take the ball away from the defensive back. When you see that with a young player, that really jumps out."

Manipulative vision

Vikings receivers coach Keenan McCardell said players typically need four or five NFL seasons before knowing how to manipulate defenders with their eyes. Sight starts at the line of scrimmage. Is the defense in man-to-man or zone coverage? What type of zone between two-, three- and four-deep varieties? That tells a receiver how to set up defenders after the snap.

"You got to see the coverage and see the leverage first," said McCardell, a former Pro Bowl receiver. "After that, you can move guys with your head, your eyes, look away."

By the time McCardell coached Jefferson for the first time last season, the receiver was already seeing the whole field and shaking defenders with head fakes matching his false steps in routes.

Jefferson's eyes are key on the underneath whip route, which begins as a slant with an abrupt cut toward the sideline. On whip routes, he's caught nine of 12 targets for 66 yards and two touchdowns, including a 3-yard score against the Seahawks last year.

"You have to take a couple more steps and show your eyes to the quarterback," Jefferson said. "That sells that slant, especially in the red zone because people think you're going to throw it quick. Once the eyes and head turn, then you snap out of it. It works every time."

'Clean' footwork

Jefferson has a pair of cleats in a glass case at home.

They were enshrined after three 100-yard games last season, including 118 yards against the Seahawks and 169 yards against the Packers. Jefferson forgot the third opponent. That's understandable: he had seven 100-yard games last year.

But he knows he'll break glass in case of emergency.

"Whenever I need that 100-yard game," Jefferson said, "I'm going to slip them bad boys on."

Quick and precise footwork makes Jefferson a terror on short (1-9 yards) and intermediate routes (10-19 yards). Defenders struggle jamming him in press coverage at the line. He shakes them with a variety of starting moves known as releases, some he's adopted from other stars like Raiders receiver Davante Adams.

"He has different releases he can do," said Vikings cornerback Chandon Sullivan, who faced Jefferson as a Packer the past two seasons. "He has a deep package now."

The dig, or an in-breaking route downfield, has been Jefferson's most productive with 388 yards on 20 catches via 31 targets. Defenders note his footwork on those inside cuts, which Vikings coaches leaned into last year as the dig route accounted for 12.6% of his targets compared to 6.2% as a rookie.

Jefferson beat Ramsey with a shallow dig for a 9-yard gain on third-and-6 last year.

"He makes those breaks and cuts so clean," Peterson said. "To where the smallest false step of the DB not being in position, he gains the advantage."

Working hands

Before yellow gloves encircle Jefferson's eyes during his famous "Griddy" celebration, they're usually making a highlight-reel grab.

But Jefferson's hands are one area where he's looking to improve. He had 13 drops in two seasons, including nine last season for a 7.7% drop rate that ranked 24th among receivers targeted at least 90 times, per Pro Football Focus. That's below his elite standard.

He's aiming for perfection, not just improvement.

"Working on my hands, always," Jefferson said. "Trying to go the whole season without drops. That's definitely a tough thing to do, but that's something I'm working toward."

The last receiver to see 90-plus targets without a drop was Larry Fitzgerald in 2019.

"I heard it," McCardell said of Jefferson's no-drop goal, "but I don't need to talk about it, because it's in his mind-set. It's what he is. The great ones know what they want and most of the time the great ones go do it."

What's the hardest pass to catch? McCardell said the hard-thrown slant, on which Jefferson has only one drop to 20 catches on 29 targets for 233 yards and a score. Sometimes a perfect pass can be the toughest, according to Jefferson, who pointed to the over-the-shoulder deep ball.

"Because it most likely passes your eyes," he said. "Once it passes your eyes, it's kind of difficult to catch, especially when it's coming over your head to the backside of the shoulder."

What's next?

Head coach Kevin O'Connell's arrival from the Rams, where he was the offensive coordinator for two years, led to immediate comparisons between Jefferson and Cooper Kupp, who last year led the league in catches (145), receiving yards (1,947) and touchdowns (16) in the Rams' Super Bowl-winning season.

But Jefferson won't be simply plugged into a Kupp role, said Vikings offensive coordinator Wes Phillips, who was the Rams' passing game coordinator.

"Cooper was playing more a slot position," Phillips said. "Just by nature of his position, he'll be doing a little bit different things than Cooper."

Jefferson's role will evolve with the Vikings offense, which he said will be "less predictable" under O'Connell by throwing out of varied and morphing formations.

Pre-snap motion was a common sight at training camp. Only the Jaguars and Steelers had as few passing plays with pre-snap motion as the Vikings in 2021, according to ESPN Stats & Info.

"The presentation will be different," said Bowen, the ESPN analyst. "There will be more misdirection in the backfield. That's all a positive for a receiver. Because you can look at that coaching tree, whether [Kyle] Shanahan, [Matt] LaFleur in Green Bay and what you'll see this year with O'Connell, and obviously Sean McVay in L.A. as well, how they create space or how they occupy defenders to create that space for a receiver."

Bowen predicted Jefferson will run more in-breaking routes, like the dig route, from play designs aimed to create mismatches on opposing linebackers or safeties. They also create chances for yards after the catch, where Kupp led all receivers last season.

The Vikings' new playbook is also expected to offer more flexibility. Phillips said multiple plays can be called in the huddle at once and decided upon seeing the defense. Jefferson will have leeway built into routes, some of which he can alter based on what he sees in the coverage.

As defenses double Jefferson more, the Vikings are planning counterpunches by giving him the chance to find man-to-man opportunities.

"Even if they're double covering me with the safety and corner, or corner and linebacker, the outside [might be] one-on-one, you know?" Jefferson said. "I'm even in the backfield now. So, it's just so many things new to this offense that I enjoy."

He will continue to chase contemporaries and legends, needing 1,148 yards to surpass Randy Moss for most receiving yardage in the first three NFL seasons, and 1,633 yards to break Moss' single-season Vikings record, a mark Jefferson came 17 yards short of last season.

"I'm not labeled as the best receiver at this point, so that's my motivation," Jefferson said. "Just becoming the best receiver and being the best teammate for my team. Just doing stuff to provide for my team and just trying to get to that main goal."