Opinion editor's note: Editorials represent the opinions of the Star Tribune Editorial Board, which operates independently from the newsroom.

•••

An assassination attempt on former President Donald Trump. President Joe Biden deciding against running for re-election. Vice President Kamala Harris stepping in to run in his place.

The breakneck pace of recent news events has many people recalling 1968. That year has long been the nation's high-water mark for tumultuous stretches outside the Civil War, with then-President Lyndon Johnson deciding not to seek a second term, with Minnesota-hewn vice president, Hubert Humphrey, replacing him at the top of the ticket, and with the tragic deaths of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy.

But the political aftermath of Biden's decision, the subject of a presidential address on Wednesday, also conjures up memories of another political era in relatively recent memory: the 1980s. That's when President Ronald Reagan campaigned on sunny optimism and easily dispatched his Democratic opponents, incumbent President Jimmy Carter in 1980 and former Vice President Walter Mondale in 1984.

Reagan's confidence and good cheer understandably felt like a tonic to voters weary of high inflation, high unemployment, an energy crisis and a hostage crisis (in Iran). He offered a fresh start, and it appealed mightily to voters of that era — a scenario that could reverberate this year.

The new energy and positivity accompanying Harris' entry into the presidential race has powerful parallels to Reagan's "Morning in America" moments. While she's not yet the official nominee, she reportedly has the support of enough delegates to win the nomination in August and has won endorsements from Bill and Hillary Clinton and Barack and Michelle Obama. This support, along with the historic amounts of money that her campaign and party raised in under a week, reflects voters' exhaustion with having 81-year-old Biden and 78-year-old Trump atop the presidential tickets and the need for both men's generation to pass the torch of leadership.

While the Star Tribune Editorial Board would have preferred a mini-primary in which challengers tested Harris' mettle, her presence on the ticket is all but certain. Her presence there feels like a shot of adrenaline to the 2024 campaign. So far she's campaigned on hope, emphasizing what works in America. It's a stark but welcome contrast from the America-is-a-hellscape narrative pushed by Trump, who is now wielding this stale playbook for his third presidential campaign.

As a sitting vice president, Harris isn't exactly a fresh face. Nevertheless, her relative youth — she's 59 — offers relief from worry about both Biden's and Trump's potential infirmities. And her story is inspiring. She's the daughter of a Jamaican immigrant father and an Indian immigrant mother. As a child, she attended California's public schools and went on to get her law degree. She served as San Francisco's district attorney, then as California's attorney general. In 2016, she was elected to the U.S. Senate.

In 2020, she smashed through a high, hard glass ceiling to become the nation's first woman vice president, as well as the first South Asian and Black woman to hold this office. Now, she's poised to break through the most stubborn glass ceiling of all: becoming the nation's first female commander in chief.

No doubt that tantalizing historic possibility has contributed to her meteoric momentum. But among the challenge ahead for her: convincing voters there are more reasons for support than breaking the gender barrier.

Harris struggled early in her vice presidential tenure to find her place in the Biden administration. A traditional VP role is serving as a congressional liaison to help pass legislation, something that Biden, Dick Cheney and Al Gore excelled at when they served under former presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Harris simply didn't have enough years in the U.S. Senate to do this well.

She also drew a difficult assignment from Biden: tackling the root causes of immigration to the U.S. — brutal Central American regimes and the widespread poverty of their citizens. There are no overnight solutions to issues like that, but how much progress Harris made is unclear. Certainly, Republicans blocking congressional funding and solutions at Trump's behest earlier this year didn't help.

Harris also has struggled in interviews and speeches to be an effective communicator, though her recent efforts to protect reproductive health care, as the Biden administration's point person on this issue, assuage some of these doubts. So do her recent fiery campaign appearances.

Figuring out Harris' current policy stances is more challenging than it should be. As of Friday, her campaign page just seeks donations and sells merchandise. That needs to change quickly so voters can make informed decisions. During her short-lived presidential campaign, she supported a Medicare for All proposal, though one that left room for private insurance companies to operate. Medicare is the federal program that provides medical coverage for Americans 65 and up, and Medicare for All proposals would allow younger people to enroll. Does she still support that?

Other key questions: Will her foreign policy differ from Biden's? She'll inherit two crises, in Ukraine and Gaza, if she wins. How will she approach both?

Her trade, agriculture, energy and education policy positions also need greater clarity.

Harris' political honeymoon over the past week has made it easy to project sunny optimism. That positivity could be a game-changer, as long as she can keep a grip on it as her record comes under scrutiny, as it should. Campaigns matter, and it's still a long way between now and Election Day.

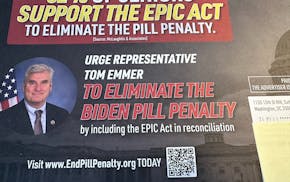

Burcum: About that so-called 'pill penalty'