GARVIN, Minn. – Relentless Opening Day rain, 20 mph winds and a flood watch in northern Murray County gave walleye chasers in southern Minnesota a morning to remember on a lake that showed a few glimpses of its star power.

"He hit like a ton of bricks,'' said Scott Ward, who hooked a plump 16-inch walleye while trolling during a lull between the driving rains.

Scott, our skipper, led us to fish on Opening Day as he always does – this year along with my 14-year-old son, Jack Kennedy. We first heard about Lake Sarah in 2018 from a state fish biologist who was studying why the lake had such an abundant, self-sustaining population of walleyes. After all, Sarah is merely 11 feet deep, surrounded by farms, impaired by zebra mussels and contained within eight miles of shoreline.

We were enticed by the fact that it's a perennial, early-season hotspot for walleyes in southern Minnesota. Adding to our curiosity was the latest Lake Sarah fishing report, issued just weeks ago by the Windom area fisheries staff of the Department of Natural Resources .

"The catch rate of walleye in 2021 was 38 per gill net, which should provide some phenomenal fishing in 2023,'' the report said. "Lake Sarah still boasts one of the best walleye populations in the area.''

Despite dismal weather on Opening Day, the lake drew 25 to 30 groups of anglers by 9 a.m. But after five or six hours of fighting to hold positions against the stiff east wind, most anglers – including us – got off the lake.

We had just a few good bites, but the walleyes we saw in boats around us were good size. Then, as we exited the lake, we saw a local man casting a weighted hook and wax worm from the public dock. On his stringer was a hefty 20-inch walleye.

Distinct genetics

For upwards of 35 years, the DNR stocked Sarah and other southern Minnesota lakes with walleye fry hatched from the huge supply of eggs gathered from fish-stripping stations at places like Cutfoot Sioux or Lake Vermilion, 300 and 400 miles to the north.

But that approach got turned on its head when Loren Miller, the DNR's fish population geneticist, took a look at the ancestry of walleyes in Lake Sarah. His study revealed a strong remnant population of fish unique to the Cannon River, which was regularly used as an egg source for walleye stocking purposes before the workload shifted to more productive stations up north.

Miller's study found that this "Lower Mississippi Strain'' of walleye persisted in Sarah and other southern waters despite decades of extensive stocking of northern strains.

"We can see through DNA fingerprints if stocked fish are helping to reproduce, and they weren't,'' Miller said. "They could add and add, but they didn't contribute to natural reproduction.''

Now and since 1991, Lake Sarah's walleye population sustains itself without stocking. Moreover, Sarah has become the primary source for DNR walleye stocking in southern lakes – inspiring more study and hatchery-aided expansion of the Lower Mississippi Strain south of the Twin Cities.

"We are not suggesting we have a super strain that would be the best everywhere,'' Miller said. "It's the principle of local adaptation. The whole thought is that this is a strain better suited for southern Minnesota.''

A follow-up study has proved overwhelmingly that Lower Mississippi walleyes inherit a distinct survival advantage in southern lakes.

From 2108 to 2022 (excluding 2020 because of COVID-19), the DNR conducted an experiment that hatched Lower Mississippi walleye eggs simultaneously and in the same facility as eggs taken from Pine River in the Brainerd Area. Equal numbers of the resulting fry were placed in the same set of southern waters in the spring. Each fall, sampling of the baby fish showed that 75% to 90% of the survivors were Lower Mississippi walleyes.

"The survival advantage was just really large,'' Miller said. "We've shown that these southern fish have a strong advantage.''

Miller said no one can explain why Lower Mississippi walleyes out-perform northern strains of walleyes in southern lakes. One possibility is that more of them grow faster in their first few months of life, giving them better odds of avoiding predators.

Miller said the DNR may possibly conduct a future study to determine what characteristics give Southern Mississippi walleyes a survival advantage in their home range, but he said the agency is not inclined to investigate how well they might adapt to lakes up north.

"In general, you want to stick close to an area's remnant genetics,'' said Miller, who has identified multiple groupings of genetically distinct walleyes in Minnesota. They include fish from Mille Lacs, Cutfoot Sioux, Pine River/Boy River and the Crow River in the Spicer area.

Ryan Doorenbos, DNR's area supervisor in Windom, said Lake Sarah is a classic shallow lake in an area formerly rich in "prairie pothole'' resources. Sarah is without dropoffs and it has little in the way of underwater structure. This time of year, before plant life takes off, locals are apt to troll crankbaits, especially along windy shorelines.

"It's a very simplistic fishery,'' Doorenbos said.

In 2015, when the DNR first tapped Lake Sarah's walleyes for fish stocking purposes, crews collected just 52 or 53 quarts of eggs, he said. But with increased familiarity of spawning patterns in the lake, crews last year collected 280 quarts of eggs. Now, in collaboration with the DNR fish hatchery in Waterville, Lake Sarah is a centerpiece in what DNR Fisheries considers its new Southern Genetic Management Unit. The strategy might not significantly increase walleye densities in the region, partly because each lake has its own carrying capacity. But biologists are confident that they'll see improved stocking efficiency – getting better results with fewer fry.

"We're hoping we'll see better natural reproduction in the lakes we're stocking,'' Doorenbos said.

"We want to be able to create more Lake Sarahs in our area.''

Federal judge approves $2.8B settlement, paving way for US colleges to pay athletes millions

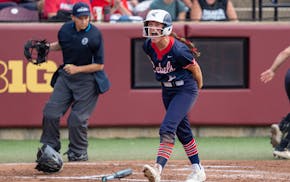

United South Central wins Class 1A softball title with overpowering pitching

St. Cloud Cathedral endures a tense start, defeats Hawley for Class 2A softball state title

Softball state tournament: Champlin Park (4A), Rocori (3A), St. Cloud Cathedral (2A), United South Central (1A) are champs