ST. LOUIS – Laurence Maroney's voice pitches up a few octaves when he's animated, usually when he's telling a story or emphasizing a point. And right now, he's making a point.

It's just after 8 a.m. and he's standing in the quiet of his living room. Decked out in maroon sweatpants and a maroon polo shirt, he scrolls through his phone looking for a notes file. He finds the document in a matter of seconds.

"Listen," he says while reading it, "college running back stats."

The file shows stats of a few great tailback tandems in modern college football history. Gophers fans already know one of them. Maroney wishes everyone knew.

"They're never going to give us the respect that we deserve when it comes to duos," he says, his voice yo-yoing with emotion.

This is Laurence Maroney today. Wistful, prideful, remorseful. He talks of his time at the University of Minnesota with exuberance. He talks of the days after with pain in his voice.

He is making a comeback in life. He's a busy father and businessman, much better off these days than those initial years that followed football when he was broke, directionless and sleeping on his mom's couch.

The heaviness of lost time in a relationship he cherished is something he can't escape. He misses his friend dearly.

Marion Barber III was found dead in his apartment near Dallas last year. He was 38 at the time, the same age as Maroney is now.

In many ways, these two Gophers greats will be forever linked. They were nearly one single person — "Barberoney" some called them — 20 autumns ago when they launched Minnesota back into national college football conversations with their record-breaking running. They remained linked after they left the university, both in the glory of NFL success and the gloom of post-football struggles.

It's those aimless years, somehow spent far apart from each other, that eat at Maroney now. He doesn't understand it. He'll never understand it. He can't get that time back.

If he could, he wouldn't put off visiting his friend. They'd talk on the phone. They'd train together. They'd ask each other for help. He'd give anything for them to be together again.

Maroney can see a scene in his mind. A beautiful day, one they never got but certainly deserved. It's a day that would show people they still have their Barberoney energy, a celebration of their greatness that drowns out a narrative derived from their life-after-football struggles.

They're at a Gophers football game. Their names are about to be announced to the sellout crowd at the stadium. Two legends, forever intertwined.

"I just see us coming back through the Minnesota tunnel," Maroney says, "and it just erupts."

Making history — together

The inaugural college football game was played in 1869. Never in the following 135 years had two teammates joined forces to do what Marion Barber III and Laurence Maroney accomplished at Minnesota.

Over two seasons, 2003 and '04, they became the first pair of teammates in history to rush for 1,000 yards apiece in consecutive seasons.

They made people pay attention to Gophers football again. Their final stats in those two seasons alone still cause heads to shake: 4,934 rushing yards, 50 touchdowns.

They were a dynamic duo off the field, too, doing media interviews side by side and even riding together around campus on a moped.

How did their tag-team excellence begin? Maroney's voice rises once again in telling this one. He is behind the wheel of his Ram 1500 pickup after dropping off his 4-year-old son at school when he begins recalling the moment they met. He doesn't just tell the story, he re-enacts the scene as if performing for an audience.

Maroney was a hotshot recruit visiting campus. The itinerary called for him to watch practice. He picks it up from here.

"The door just bursts open," he says, his voice becoming loud and theatrical. "I can see this big shadow walking through the door. I remember he was jacked. I'm like, who is that? Everything about him was tough."

He heard someone say the name Marion. Maroney didn't know the names of any of the running backs. Hearing it meant nothing to him.

"He didn't say one word to me," he continues. "And I didn't say one word to him. It was like two pit bulls having a stare-off. We were sizing each other up. I'm not about to break character and he wasn't either."

Maroney pauses to mimic their expressions that day as his truck rumbles down the freeway.

They were the oddest of odd couples, their personalities as different as the sun and moon. Barber was an extreme introvert from the Minneapolis suburbs and Wayzata High School, Maroney an extreme extrovert from St. Louis.

Their running styles offered a counterbalance too. Barber punished defenses with power. Maroney had sprinter's speed.

Their partnership appeared cosmically aligned. Maroney wore No. 27 in high school because of his idol, Eddie George. He has the number tattooed on his arm, and he wore it during training camp as a true freshman. But when he showed up for his first game, he found uniform No. 22 hanging in his locker. Barber wore No. 21.

"It just made sense," Maroney says, "The 1-2 punch."

That punch was forceful. That initial stare down didn't last.

Their acceptance of each other did as much to shape their legacy as their statistics. They admired each other's talent and cheered each other's success. They subbed out during games without complaint. Oftentimes, they made that call themselves with a quick tap on the helmet. And when the Gophers defense was on the field, they rode stationary bikes side by side on the sideline to stay ready.

"It was almost comical in practice because they would say, 'You take this, no you take it, no you take it,' " former coach Glen Mason recalls. "I used to get asked who's going to start. I'd say, 'Don't ask me, ask them.' I really didn't care."

The athletic department promoted them together in marketing efforts, splashing their photos across billboards and city buses and the cover of the team's 2004 media guide. They preferred to conduct media interviews together, with Maroney answering most of the questions, which delighted Barber.

Maroney had a key to the Barber family home in the suburbs in case he wanted a break from campus. He could go anytime, even if Barber wasn't with him.

"There is nothing that I can say or even Laurence can say that will really paint the picture of their friendship and relationship," says Dom Barber, Marion's younger brother and Gophers teammate of both. "You had to see it live. As my dad would say, it was a beautiful thing."

Their moped jaunts became a staple of Mason's speeches on the banquet circuit. As legend goes, one day Maroney was driving his moped with Barber seated on the back. Mason was stopped at a red light when his star running backs zoomed through the intersection, neither wearing helmets.

"We're just flooring this thing," Maroney recalls. "We're having a good ol' time. As we come floating through campus, we see him. You should have seen Mason's face."

Maroney opens his mouth and eyes wide to simulate shock.

"It was funny," he says. "We were just being us."

Their competitiveness fueled a friendly wager: Whoever had the fewest rushing yards in a game had to pay for the other's dinner at the former Dinkytown restaurant Steak Knife. But only after a victory.

"I was a modest eater," Maroney says. "But MB, he wants extra toast. I hated for him to win because it's going to cost. If he got rolling in a game, I'd be like, hold on, I can't keep paying for you to eat. It's taking all my Pell Grant trying to feed you."

That their connective tissue was so strong in their glory days makes their years apart so confusing now for Maroney. This period in their lives was, like so many things between them, a shared experience, happening at the same time. Only this time, they were hundreds of miles apart.

Both were out of football, searching for a new path. There was legal trouble, detachment and mental health struggles. The dynamic duo had a gap of five years without talking to each other. Not intentionally or because of a dispute. It just happened.

Then a phone call came one day. They reconnected then and every so often after that, but occasional calls were not enough to prevent regret and sadness that now can't be shed.

Barber died in June 2022 of what a coroner labeled an accidental heat stroke. Police conducting a welfare check found him dead inside his Dallas-area apartment with the thermostat set to 91 degrees. He was training to be a boxer and was known to exercise in extreme heat.

Later that month, Maroney was at the Gophers stadium in a public memorial to remember Barber.

"Marion was not just a teammate to me," he said on stage that day. "He was truly my brother and this one hurts, and it hurts deeply."

Barbarian? Only on the field

Dom Barber picks one of his brother's favorite spots to meet and share stories. Marion loved Parkers Lake in Plymouth because he found it peaceful. He enjoyed fishing off the dock.

Much of Marion's life remains a mystery to fans and the followers of his career. He was a private guy. Those in his inner circle knew Barber as being gracious and goofy, protective and loyal.

Football fans gave him the nickname "Marion The Barbarian" because of his running style. In seven NFL seasons, he scored 60 touchdowns. His family considered him a softie.

"When he was on the gridiron, that's when you got the Barbarian," Dom says. "When he was off, he was as gentle as you could want in a person."

The public's perception of his brother bothers Dom to this day, and it bothered Marion, too.

"He did struggle with people talking about him who didn't know who he truly was," Dom says.

Two arrests post-football are a matter of public record. One in 2014 for bringing a gun to his church, which resulted in Barber being taken for a mental health evaluation. The second arrest came four years later on misdemeanor counts of criminal mischief reportedly after he ran into cars at an intersection crosswalk while he was jogging.

These fueled a narrative that Dom says misrepresents his brother.

"[He's] not the guy that is portrayed the last few years," Dom says.

Dom could share hours-worth of stories that don't suggest struggle. Like the time Marion planned a surprise trip to Costa Rica for Dom and 10 of his buddies. Marion covered the cost for the entire group, which included a helicopter shuttle from the airport to the 12-bedroom home he rented that came with a private chef and concierge.

In college, Marion organized the team Bible study on Thursday nights and dragged teammates out of bed on Sunday mornings for church. He became quite talented on the piano and particularly loved performing Coldplay songs. Once, while visiting Dom in Houston when both were in the NFL, Marion was incredulous that his brother didn't own a grill. He went out and bought one and then stocked his brother's fridge with steaks.

These joyful stories can't erase Dom's sadness, though, and his own regret.

"What hurts me the most is, could I have done more? Should I have done more?" he says. "I think about that all the time."

He says there were periods in the final years when Marion would go a few months without communication. Dom knew Marion was searching during these times, looking for the next thing to make him happy.

"There was a time when he struggled to find himself," Dom says. "He knew he could do more. He wanted to do more. He just didn't know how to get his ducks in a row to do it."

He considered starting a trucking company but that didn't materialize. He wanted to get more into boxing. He wanted to work with kids and provide for his community. The gap between his ideas and reality proved too wide.

Did he struggle with mental health? Maybe, Dom says, but he views it more as "heartbreak" caused by different factors.

"Each year, it was always something and his heart kept getting broken," Dom says. "He got to a point where he secluded himself."

The family found surprise discoveries while cleaning Marion's condo after his death. He had journals filled with entries written as scriptures. He also had notebooks outlining a vision formed on a visit to Brazil one year with Dom, complete with drawings and concepts. Marion wanted to create a multi-purpose academy for underprivileged kids in Dallas, a place for education, coaching, the best of everything.

"Kids brought him joy," Dom says.

So did his own family, no matter how difficult his days. Marion's family knew he loved them. He ended every conversation with Dom the same way, by saying the same word: Unconditionally.

Sitting on a bench overlooking a lake that his brother found peaceful, Dom plays a voicemail from Marion in 2019. Marion mentions that he is picking up their younger brother Thomas at school and makes plans to see Dom and his wife and their kids the next day. Marion ends the call with his standard sign-off, his last word, then and always:

"Unconditionally."

Maroney's comeback

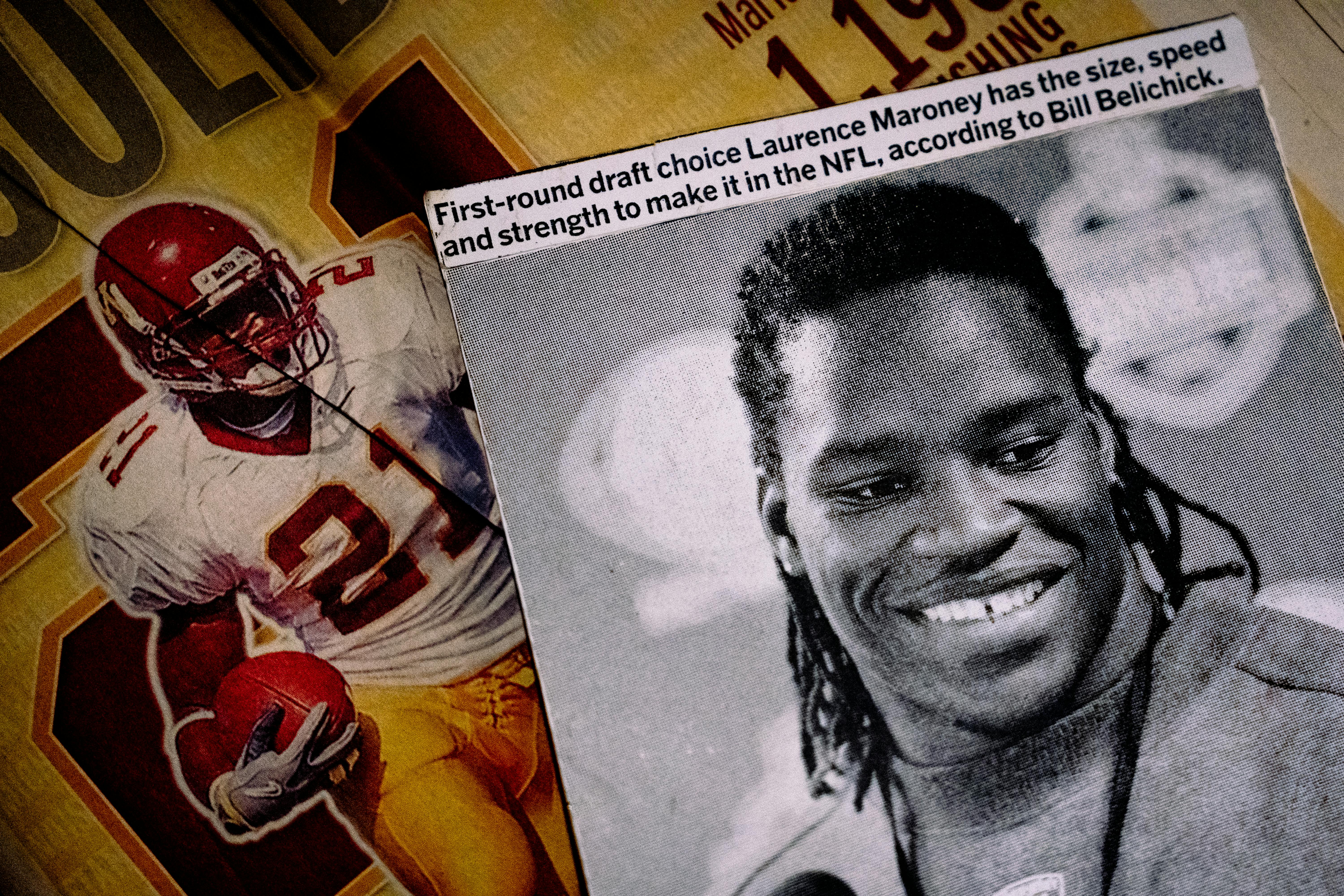

The basement in Terri Terrell's home is dedicated to her son. She put together three memorabilia sections that chronicle Maroney's journey: high school star, Gophers record-breaker, and an NFL career that peaked when he was the leading rusher on a New England Patriots team that went 16-0 in 2007 before losing in the Super Bowl. Maroney scored his team's first touchdown in that game.

When the meter on his football career expired, life became blurry. He traces rock bottom to 2014, but the slope that took him there started January 2011.

He became a free agent after an injury-marred season with Denver. He had been home in St. Louis only a few days when he was arrested on a misdemeanor marijuana charge along with several people in a car. Maroney said a group of friends were driving to a concert. Police found guns inside the car, but Maroney had a permit to carry and was not charged.

The timing of his arrest was awful. He was a 26-year-old free agent, and the NFL went through a lockout that offseason. Maroney fought the marijuana charge, and his case stretched into late August before a judge found him not guilty. The damage to his reputation was done. After five NFL seasons, he was unwanted.

"Life did an upside-down turn for me," he says.

He says he got into the best shape of his life over the next two years, waiting for NFL coaches to call. He tried out for the Canadian Football League but injured his leg during the workout.

He had lost his place in the game. He would soon lose everything else.

By 2014, the money he had in savings, whatever was left from $8 million in NFL contracts, was gone. He had to short-sell a condo in Miami. He moved back into his childhood home with his mother, sister, her two children and her partner. Maroney slept on the living room couch for a year.

"It was just dark times," he says. "I didn't know how to get out of the funk. I felt like I was in a deep hole and no matter what I did, I was getting further and further in the hole."

Three separate disability payments from the NFL, including a concussion settlement for $1.2 million in 2020, helped Maroney get back on his feet. It was a process that required him to visit multiple neurologists and specialists in different states over several years.

His financial standing stabilized, Maroney threw himself into real estate ventures, but his emotional and mental health continued to deteriorate. Looking back, he understands now that he suffered from depression and anxiety. He either couldn't or wouldn't accept that he needed help.

He chose to suffer in silence, completely lost without football.

"That's all I knew," he says. "When they took that away, I felt like Laurence Maroney himself was gone. I didn't see the value outside of football because football brought me everything. When that was taken away from me, I felt like everything was taken away. I felt like my whole identity was gone. Who am I now?"

His ultra-confident personality suddenly became a façade. He felt like a stranger in his own hometown that once celebrated him.

"I had an identity crisis," he says. "I felt like I was living a double life. When I come outside, everybody sees Laurence Maroney. But to me, because I don't have money or this or that, I'm not him. I had to put on a front."

A relationship that began in 2018 rescued him. Briante Wells didn't know Maroney or anything about his football career. She wasn't all that impressed with him when they first met, but they started dating and soon had a son together named Laurence Jr., LJ for short.

Wells often heard people talk about Maroney's life-of-the-party spirit. She kept asking herself, Where is this person people keep telling me about?

Maroney was still closing himself off. Wells pushed him to open up.

"I'm like, you can't tell me you're just content and happy with being in this house playing video games," she says. "I'd ask him, 'You're fine with this? For the rest of your life?'"

Wells convinced him to try therapy, and to re-establish his foundation with a focus on bringing awareness to mental health by sharing his own experience.

His LM39 Foundation sponsored a community event in May that brought 25 organizations and vendors together for an athlete mental health awareness field day.

"Life is better, but I still have my moments," he says. "With mental health, there is no cure. You just learn to cope and deal with it."

'Hurts every day'

Maroney doesn't watch football on TV. Just boxing. And HGTV, a channel he consumes for hours at a time. He and Wells, a realtor, know every show, and Maroney has developed a keen eye for decorating and home remodeling. The couple owns several rental properties, and they renovate and flip houses.

His high school retired his jersey number this fall, and he was chosen to be commissioner of a county-wide flag football league. He is tasked with finding players, coaches, officials, football fields — everything.

Those ventures and a blended family of five keep the couple busy, but that doesn't stop the past from pulling at Maroney.

"It hurts every day to think about it — about all the time that we missed," he says of Barber. "It makes me think, man, why wasn't I training with him in the offseason? Why weren't we linking up? I'd give anything to go back and get some of that time back. I know I wasn't that busy and I know he wasn't that busy, to where we couldn't have gotten that time in."

A sliding door hides a private room in Maroney's basement. A sign above the decorative barn door reads "Man Cave." This is where he keeps his treasures.

He reaches into a closet and pulls out something wrapped in blankets and a plastic bag. He unwraps it to reveal a large painting of Barber in his Cowboys uniform. He's carrying a football in the rendering.

Maroney paid $1,200 for it during an auction at a gala supporting Barber's foundation when he was alive.

"I wasn't going to let anyone outbid me," he says.

Maroney is on the move again. His smile, his energy, it's what we remember. Even some of his speed is still there. He mentions occasionally getting on a track and running a 200-meter dash to show anyone watching that he's still fast.

"Some stuff you just don't lose," he says, defiantly.

He might get to walk out onto the Gophers football field again someday, too, an all-time great getting a standing ovation for his glory days. It can't be that moment in his dreams, with Barber by his side. It will be one-half of the dynamic duo that re-lit Gophers football's flame 20 years ago.

Maroney will be back in Minnesota, regardless of ceremonies to come. He hopes visiting his friend's final resting place will bring peace and allow him to feel their connection again. Maroney has made a promise to honor Barber by visiting his gravesite every year on June 10, Marion's birthday.

"At the end of the day, we knew each other's heart," he says. "We knew our relationship. We knew what we meant to each other."