The depth of influence a person can have over a sport isn't instantly obvious. It can take time for meaning to take hold or for society to realize that an athlete's exploits or coach's philosophies, which seemed small or personal, were taking root and blossoming into something else entirely.

For the 10 newest selections to the Minnesota Sports Hall of Fame, their individual passions changed the trajectory of sports in the state and across the country.

The new class will be inducted March 1 at the Mall of America, in conjunction with the Big Ten Conference as the women's basketball tournament begins in Minneapolis. Staff members of the Star Tribune, owner of the Hall of Fame, chose to recognize Big Ten alums in this year's class to commemorate the tournament coming to Minnesota for the first time. The voting took place late last year, and here are the 10 legends of Minnesota sports who make up the Class of 2022:

A plan to be a physical education teacher after graduating from the University of Minnesota got sidetracked when Jean Freeman was asked to stay on and coach the Gophers women's swimming team, where she swam from 1968-1972, for $50 in 1973. She would stay on for 31 years, win two Big Ten titles, coach 58 All-Americas and become the first woman to earn the Outstanding Service Award, the highest coaching honor in collegiate swimming. "I've enjoyed it," Freeman told the Star Tribune when she retired in 2004, "but I didn't think I would spend this much time doing one thing." The Jean K. Freeman Aquatic Center at the U was named for her in 2014, four years after she died of colon cancer.

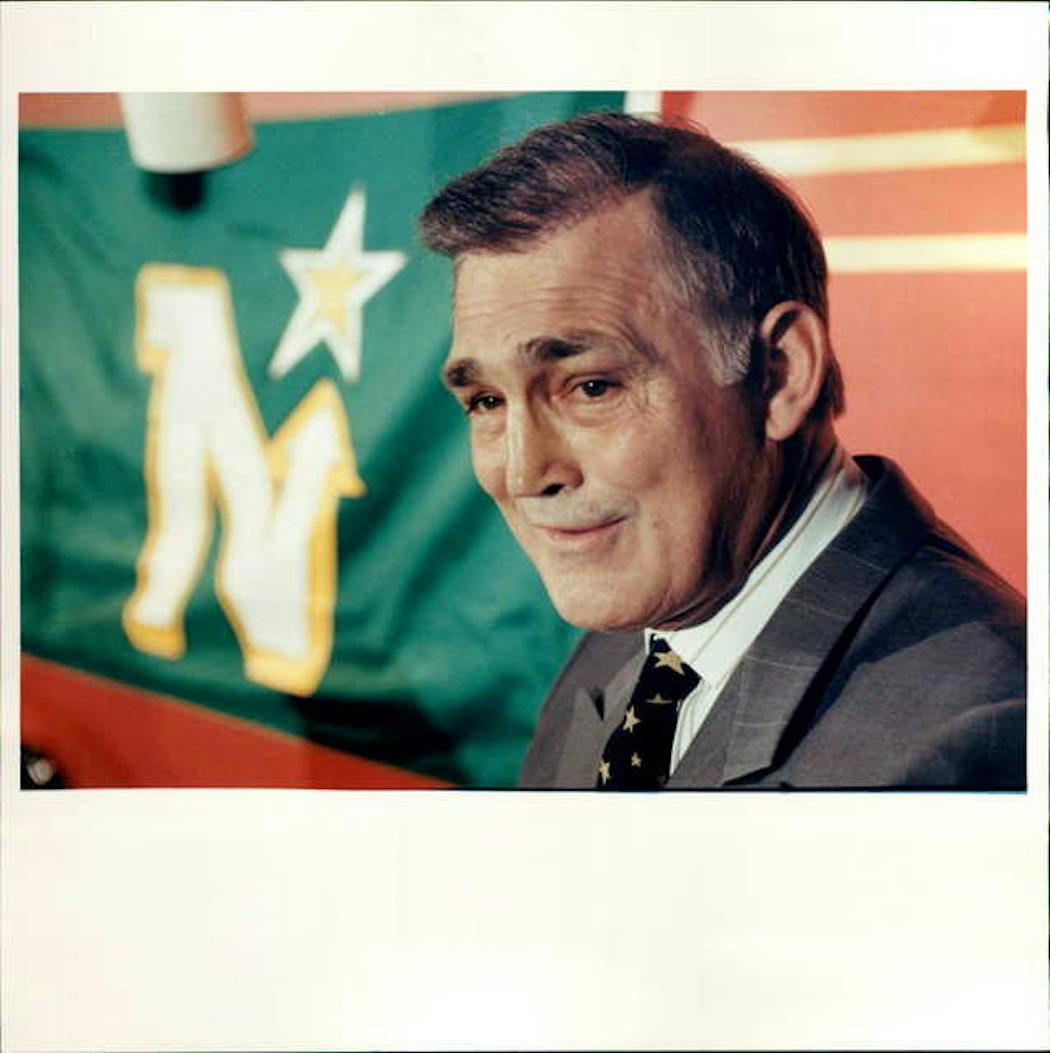

There isn't a coach whose name is more synonymous with the sport of hockey than "Badger" Bob Johnson. His positive spirit radiated throughout the game from his start coaching Warroad High School in 1956 to a historic run with Wisconsin from 1966-1982 and leading USA Hockey before stops in the NHL with Calgary and Pittsburgh. The Minneapolis native played for the Gophers and when he won the Stanley Cup with the Penguins in 1991, he did it minutes from home, topping the North Stars at Met Center. Shockingly, Johnson would die of brain cancer six months later, but his legacy has been unending — to the point that his saying, "It's a great day for hockey," has become a de facto motto for the sport.

It wasn't just that Paul Krause changed the parameters of what a defensive back could be in the NFL — it's that no one has done it better since. The all-time interception leader in the NFL, with 81, was a roving, instinctive free safety who starred on the Vikings' famed Purple People Eaters from 1968-1979, reaching four Super Bowls. When the former Iowa Hawkeye finally was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1998, after 13 long years of waiting, he told the Star Tribune of his interception record, "I'm very proud of it. I hope it's not broken, even though records are made to be broken." So far, no one has gotten close.

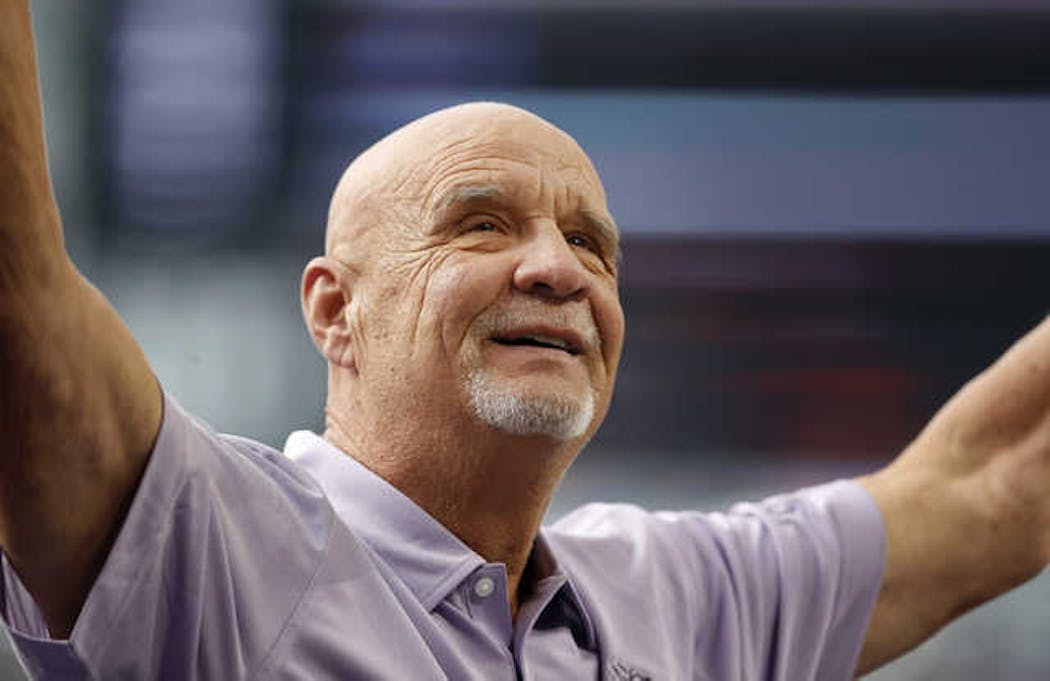

If this is the state of hockey, then Lou Nanne is the ambassador. He came to Minnesota from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, in 1960 and was an All-America standout for John Mariucci and the Gophers. Then he played 11 seasons for the North Stars, and was general manger for over a decade, while also serving in leadership roles with the NHL and USA Hockey. In recent years he helped the U of M with a massive fundraising campaign, opened a steakhouse in Edina, and watched his grandkids continue to play and work in the game. For 58 years he has been calling the Minnesota boys high school hockey tournament. None of these are his day job. "When I played I figured a lot of guys were going to beat me out in raw talent," he told the Star Tribune in 1980. "But I was never going to lose my job by not working hard."

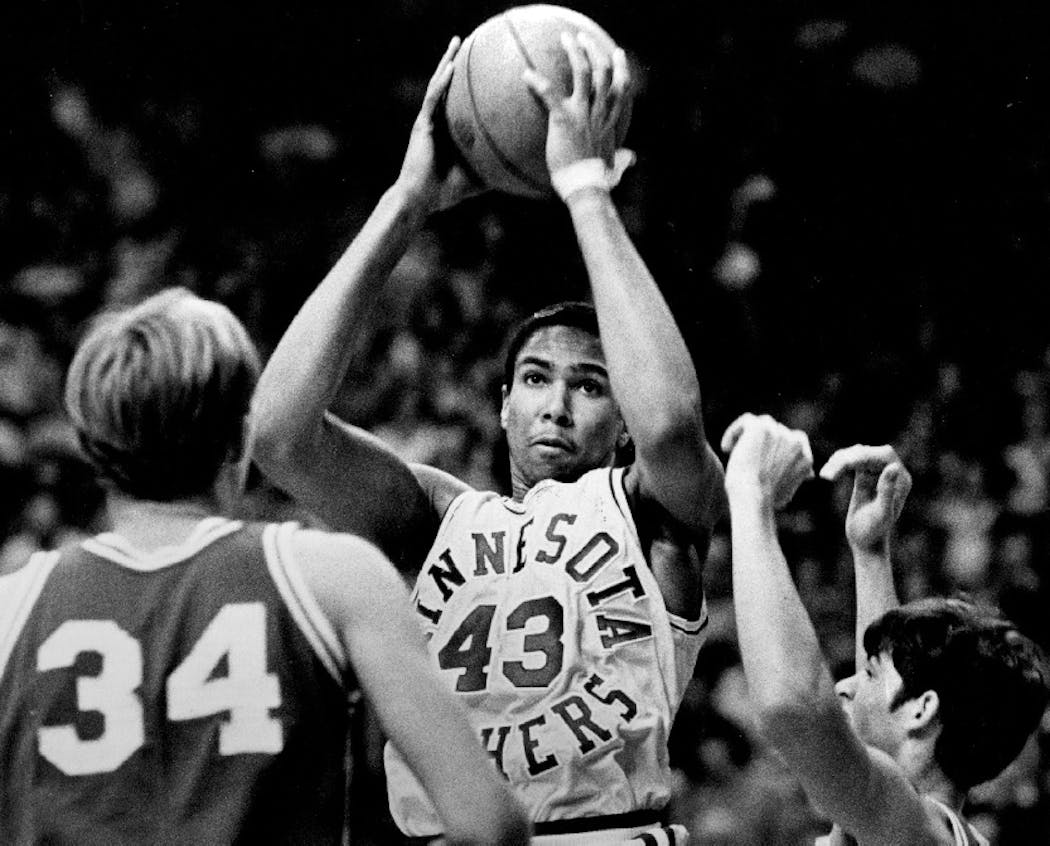

Linda Roberts' accomplishments for basketball in Minnesota are multifaceted. She is a pioneer, the first African American woman to play for the Gophers and the only Black woman with her jersey retired at Williams Arena. She was the team's first star, a ferocious center who graduated as the U's career leader in points and rebounds — the rebound total of 1,413 still stands. And she has been a friend and mentor for decades to children and teenagers in the Twin Cities, including connecting them with players at the U, where she continued to work after her playing days. When her jersey was raised to the rafters in 2006, Roberts told the Star Tribune with understatement, "I was all right. I got the job done."

No one could score like Carol Ann Shudlick. The Apple Valley native joined the Gophers in 1990 and proceeded to set the basketball court on fire, bringing the program to heightened relevance while being named the NCAA National Player of the Year in 1994. Her 2,097 career points would stand as the program benchmark until Lindsay Whalen broke it a decade later. But while Whalen would go on to WNBA stardom, those avenues weren't available to Shudlick. "I've been playing basketball since I was in fifth grade, and it has rewarded me with many things," she told the Star Tribune in 1993. "But there aren't too many places open to keep playing once I'm out of college. ... So it may be that I'm going to have to find a job when the season is over."

During a stretch from 2000-2001, Katie Smith couldn't stop making basketball history. She won a gold medal with Team USA at the Sydney Games. She became the first woman in any sport to have her number retired at Ohio State. During the 2001 season with the Lynx, she just kept breaking WNBA records, including: points in a single game (46); points in a season (739); points per game (23.1) and minutes played (1,234). But the team struggled, "I want to win," she told the Star Tribune at the end of the year. "That's the only way you get respect." Smith would play 12 more seasons, win two titles with Detroit and retire as the league's second-leading all-time scorer. She was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2018. In 2020 she returned to the Lynx to work under Cheryl Reeve, and remains an associate head coach.

In Vikings history no one carried out the core defensive element of football — go get a tackle — better than Scott Studwell. The former Illini star remains the franchise leader for tackles in a career (1,981), single season (230), and game (24). But it was more than his 14 seasons at linebacker that tied him to the franchise — it was also the 28 years he spent as a scout, amassing more than four decades as a foundational element of the organization. During his final playing season in 1990, he told the Star Tribune, "There's always a question mark in your mind as to whether you can be as successful on the outside as you were in the game. I realize it's going to be a tremendous adjustment." He handled it with ease.

The Gophers didn't wait long to retire Mychal Thompson's jersey. They did it at the halftime of the final game of his senior season in 1978, a few months before the 6-10 center from Nassau, Bahamas, would be selected No. 1 overall by the Portland Trail Blazers in the NBA draft. It was an easy decision. Thompson left the Gophers as the Big Ten's all-time leading scorer (1,992 points, 20.8 per game) and the U's all-time leader in rebounds (956). "I'd like people to remember that I was a nice guy, nothing special," he told the Star Tribune before the final game of his Minnesota career. One would be easier than the other. Thompson would go on to play 12 years in the NBA and win two titles with the Lakers — where he has worked as their radio color commentator for 20 years.

Mick Tingelhoff came to the Vikings with little fanfare. The center had graduated from Nebraska and played in the Senior Bowl, but wasn't selected through 20 rounds and 280 picks of the 1962 NFL draft. He signed as a free agent, immediately showed his talent and was named the starting center in his rookie season. He would not relinquish the position for 17 years. During that time he started 240 consecutive games, played in four Super Bowls and made seven NFL All-Pro teams. He would, after a long wait, become a Pro Football Hall of Famer in 2015. Tingelhoff died of Parkinson's disease and dementia in 2021. Announcing his retirement in 1979, he told the Star Tribune, "When training camp opens they might say to the new center, 'Tingelhoff did it this way, so why don't you try it this way.' But in a couple of days I'll be forgotten." That was one of the few parts of the game he was incorrect about.

Softball state tournament: Champlin Park (4A), Rocori (3A), St. Cloud Cathedral (2A) are champions

Champlin Park turns a big moment into the Class 4A softball championship

Rocori rolls past Byron in Class 3A for its first state title in 11 trips

Gophers men's hockey team adds defenseman Finn McLaughlin, who flipped his commitment from Denver