Margot Imdieke Cross' influence is everywhere.

It's reflected in curb cuts on streets, aisles next to disability parking spaces and the size of accessible bathroom stalls. It's in the seating arrangements and braille signage at Target Field and entrances and ramps at the State Capitol. And in the paved trails at Gooseberry Falls and William O'Brien state parks.

"Margot changed the lives of thousands of people," said Sharon Van Winkel, who met Imdieke Cross on a women's wheelchair basketball league in 1975. She watched her friend go from teaching teammates to pop a wheelie to get into hotel rooms in an era when little was accessible to becoming a "powerhouse" who compelled contractors and state lawmakers to make infrastructure and policies more equitable.

The disability rights advocate, who spent decades fighting to make the country more accessible, died of cancer on July 21. She was 68.

Imdieke Cross was one of eight kids growing up on a Sauk Centre dairy farm, where an accident injured her spinal cord when she was toddler. She was "strong-willed" and improvised solutions to navigate life on the farm, her brother Tim Imdieke said. When she moved to the Twin Cities to attend the University of Minnesota she continued to run into accessibility challenges, he said, including having to climb up the stairs on city buses.

"Her life gave her a [belief that] something's got to change," Imdieke said. "Something's got to happen here, it's not right. And she just had a fever to make things accessible."

Friends and former co-workers described her as tough, determined and stubborn. She was fearless and feared, but also good-humored and deeply caring.

"Everybody talked about how fierce she was, but she was also very kind and very understanding," said Greg Lais, founder of the nonprofit Wilderness Inquiry that aims to make the outdoors accessible to all. Lais said a Boundary Waters trip with Imdieke Cross when they were in college was a "turning point in my life."

Frustrated by being carried "like a sack of potatoes" across one portage, Imdieke Cross proceeded to crawl the length of a portage, dragging her wheelchair, Lais said. That trip spurred "a realization that people with disabilities could do whatever they want to do in the wilderness or anywhere," he said.

When President George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act into law in 1990, Imdieke Cross was at the event. She proceeded to do more than any other Minnesotan to push for and implement the Act, said Sen. John Marty, DFL-Roseville.

She sought to improve the lives of people with all sorts of disabilities, Marty said, including those with mobility limitations, sensory impairments, deafness and blindness, and people with mental health challenges.

"I can't think of anybody in Minnesota who has done more for accessibility," he said. "She cared about people, period."

Imdieke Cross spent the bulk of her career — about 35 years — working at the Minnesota Council on Disability. She also served on various commissions and committees.

When she was the state accessibility specialist and Joan Willshire was the council's executive director they would play "good cop, bad cop" with lawmakers and building contractors, Willshire said. Imdieke Cross relished the bad cop role, said Willshire, who liked to warn people: "Don't make me send Margot."

"She could make grown men, these building code officials, not cry, but really whimper," Willshire said. "She knew her building code."

Imdieke Cross mentored David Fenley, the council's ADA director, who said her approach was, "If we're not making people mad, we're not doing our jobs. Because we're supposed to push for change, push for increased rights."

She was involved in nearly every major sports facility construction project in Minnesota in the past two decades, from Allianz Field to US Bank Stadium, Fenley said. She was heavily consulted on the design of Target Field, he said, which was widely regarded as one of the most accessible stadiums in the nation.

She was also keen to take on individual's needs and frustrations, whether that was making a call about unplowed disability parking spaces or ensuring a friend could bring a service animal to the Guthrie, Van Winkel said.

Over the decades, friends and coworkers said she earned first-name-only status in the disability community.

"Elvis, Beyoncé, Cher and Margot ... All you have to do is say the first name and we know who we're talking about," Van Winkel said.

While she is known for her ceaseless advocacy on disability rights, her friends also described her as a feminist who loved her husband, Stuart Cross, and enjoyed going out to restaurants, listening to music, getting outdoors and laughing with friends. She is survived by her husband, of Minneapolis, six of her siblings and many nieces and nephews.

A celebration of life is scheduled from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Aug. 7 at Banquets of Minnesota in Fridley.

Marty, who will give the eulogy, spoke with her in the weeks before she died. He said she lamented that many accessibility fights lie ahead and requested that others "keep up the battle."

In the program for the celebration, Imdieke Cross wrote a goodbye, adding an apology to those she may have offended along the way — "unless you had it coming!"

"Sometimes passion pushes politeness aside," she wrote. "Thank you again for your love, support, and camaraderie. May we meet again where the ramps are gentle, interpreters abound, and access is for all."

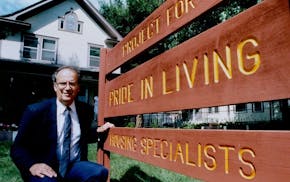

Joe Selvaggio, social change agent who started Project for Pride in Living, dies at 87

Bemidji State University women's volleyball coach dies of cancer at age 41

Former Minnesota veterans commissioner, who resigned after ALS diagnosis, dies at 61

Axel Steuer, who guided Gustavus Adolphus College through 1998 tornado, dies at 81