When Maya Washington was growing up, her father wore a suit and tie to work as an executive at 3M, where he built a distinguished career managing workplace diversity.

But she was an adult before she learned the details of how, decades earlier, Gene Washington, a former wide receiver for the Minnesota Vikings, had helped diversify his own workplace, so to speak, as a member of a champion college football team.

"He had a whole life before I was born," said Washington, who lives in Minneapolis.

She knew her parents had grown up in the segregated South. But she wasn't aware of the historic significance of her father's role in integrating college football, or the ways that affected her own life.

When Washington, a stage and film actor, choreographer, director, playwright and author — "not a football person," she said — learned how acclaimed a football player Gene Washington had been, and what a big deal it was when he was recruited to play for Michigan State University, she launched a quest to explore his past.

His story inspired her to make a 2018 documentary, "Through the Banks of the Red Cedar." Last year she published a book of the same name, subtitled "My Father and the Team That Changed the Game," which was a finalist for this year's Minnesota Book Awards in the general nonfiction category.

"The intention in my heart wasn't to create a hero piece but to document a story that many people these days do not know," she said.

The film features appearances by several legendary former Vikings, including Alan Page, Carl Eller, and the late Joe Kapp. It has been screened at the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival, the College Football Hall of Fame in Atlanta, the Minnesota Vikings' Twin Cities Orthopedics Performance Center in Eagan, Michigan State and other institutions and colleges.

Washington has traveled the country with her father, visited classrooms, given speeches and spoken on Zoom. She talked to a student who did a Black History Month project on Gene Washington. "The other kids wanted to do LeBron James," Washington said with a characteristic laugh. "She convinced them to do the project on my dad."

She also has assembled community and school discussion guides to help others explore their own parents' pasts, with questions such as: "Is there anyone in your family or community who lived through an important moment of history? If so, who are they and what did they experience?"

She's completing lesson plans that could be used next school year. At the Young Authors Conference on May 30-June 1 at Bethel University, she plans to present a program on making a creative project, for an audience outside one's family, based on a true story.

"I don't know that everyone has to make a documentary or write a whole book," she said. "Could be a performance piece, could be a poem."

She encourages people to ask their parents questions while they can, particularly if their parents endured trauma and hardships.

"Why I want to plant the seeds with children is that a story is sacred," she said.

An opportunity

Gene Washington grew up in La Porte, Texas, a small city southeast of Houston, attending an all-Black segregated school. In high school, he had to take a bus to nearby Baytown because his own city didn't have a high school for Black students. That's where he met his future wife, Claudith.

He played football in an all-Black high-school league, but after graduating couldn't play for the still-segregated University of Texas. In the early 1960s, coaches in the North spotted an opportunity to strengthen their teams by scouting Black players from the South. Washington was among a handful recruited by the Michigan State Spartans.

In "Through the Banks of the Red Cedar," Gene Washington recalls his first-time experiences in an integrated setting: traveling in a plane, being picked up by a white driver, eating in a restaurant, entering a hotel through the front door.

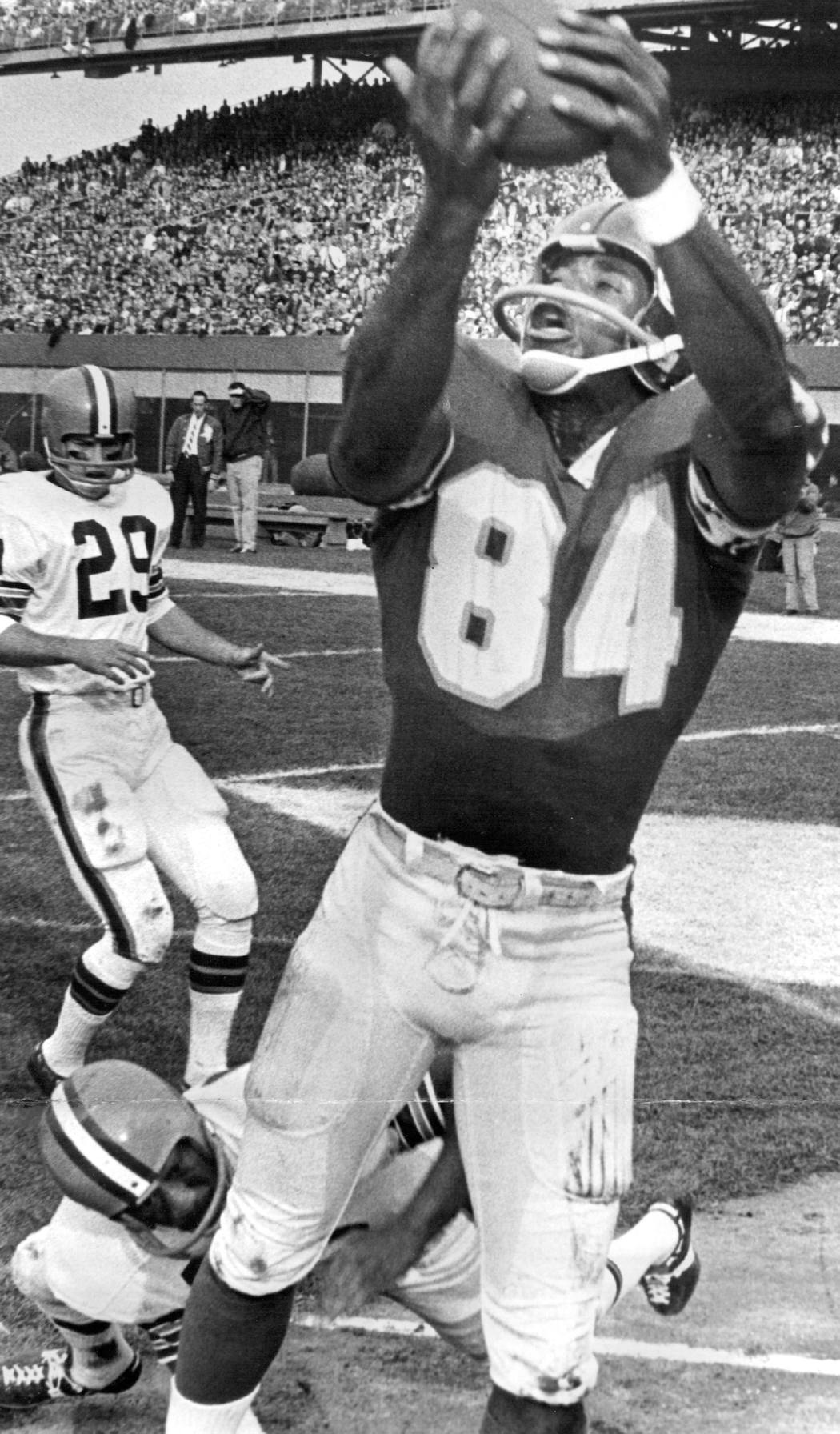

The Spartans were Big Ten, national champions and played in the Rose Bowl. Washington, who also was a track and field star at Michigan State, was later inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

After graduating in 1967, Washington was among four Michigan State first-round draft picks, all of them Black players, for the National Football League. He was No. 8. He is listed among the "50 Greatest Vikings."

Maya Washington began to learn more about her father's football history in 2011, while attending a memorial service for his friend Bubba Smith, another Texas native who was recruited for the Spartans — who then recommended Washington to the coach — and later played for NFL teams.

"I was at a point in life where I was starting to pay attention and recognize that this was a significant milestone in my father's life," she said. "All these little things were really fascinating, and I felt regretful that I was just learning about my dad."

Following her dad

Washington realized that her father had helped lay a foundation for her own childhood. She and her two sisters were among only a few Black students in Wayzata Public Schools. She experienced plenty of microaggressions, before that word existed, and a sister was routinely taunted with a racial slur.

"The weight of everyone's understanding of Blackness, of people of color, was on our shoulders every day," she said.

She remembers feeling a sense of foreboding when, on a family road trip in Northern California, her father was pulled over by a police officer and asked to step out of the car. Funny ending, though — her father came back to report the cop had said, "I know who you are, you're [former Minnesota Twins star] Rod Carew."

Her knowledge of the restrictions her parents had experienced in a segregated society helped fuel her commitment to succeeding in school. "It made me conscious of the opportunities that had been afforded to me because of what my parents didn't have," she said.

Now she hopes her own experience and the study guides she offers will inspire others to investigate history of their own families, and her learning materials will help guide people to start those conversations.

Unlike many people in earlier eras, people now have the "gift of access to things," even as simple as paper and pens, she said. Ancestral research has become easier thanks to letters, photographs and so on.

"We have really powerful opportunity to document the past," she said.

Or, as Gene Washington's college coach, Hank Bullough, puts it in the film, "I tell you this, you young people out there, go back and look up and find out where you came from."

Streetscapes

Critics' picks: The 12 best things to do and see in the Twin Cities this week

6 new foods worth trying at a Timberwolves game