Salvador Ramirez, a meatpacking worker at JBS in Worthington, died alone in a house not much bigger than a studio apartment a mile from the plant.

His state death certificate said he was 53, but he was 66, said his wife, Maria. The two had been married for 25 years and raised two sons in Chicago. They lived separately after he started working in Worthington.

Ramirez had diabetes. When his wife first saw reports of a COVID-19 outbreak at the plant, she called him.

"I was pleading with him to be careful," she said. "He told me they kept making him work. He told me he felt sick, but he told me they were all working."

Less than three months after the nation's meatpacking plants became hotbeds for the coronavirus, meat production is nearly back to normal. But workers and their families are still paying the price.

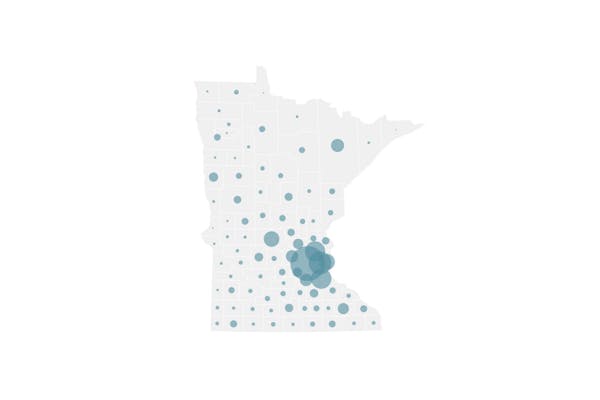

More than 30,000 meatpacking workers have fallen ill from COVID-19 nationally, according to data compiled by the Food and Environment Reporting Network, with outbreaks at every major plant in Minnesota and Iowa. At least 100 have died. Others have seen their lives upended or permanently altered.

Their power steadily eroded for decades, workers had little recourse when President Donald Trump, during the brunt of the pandemic in late April, ordered meatpacking plants to stay open so consumers could be fed and farmers wouldn't have to euthanize animals they couldn't get to market.

Line workers at slaughterhouses are predominantly people of color, immigrants or refugees for whom English is a second language. For some, other job opportunities are limited. Where unions are active, which is only in scattered pork plants and very few chicken slaughterhouses, they are relatively weak.

"The basic issues in the industry are going to be the same" in a pandemic as always, said Don Stull, an anthropologist at the University of Kansas who has studied meatpacking plants for decades. "The industry is built on high productivity, getting it out the door, hitting the numbers."

Hitting the numbers meant keeping workers on production lines, or pushing them back as quickly as possible at plants that temporarily shut down. Millions of dollars have been spent on COVID-19 safety measures at the plants, but testing has been uneven and data remains scarce.

Minnesota tracks cases by county but doesn't regularly publish cases at plants, and isn't tallying meatpacking plant deaths separately. In South Dakota, Smithfield Foods is trying to prevent a federal agency from accessing data about its workers that was collected by the state health department. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which published an inaccurate tally of cases in early May, has released nothing on the subject since.

JBS USA, the company that employed Ramirez, said in a statement that it mourns his death. The firm said it has conducted mass COVID-19 testing at the Worthington plant and participated in contact tracing with local health authorities.

No one has been furloughed or fired at the plant. "No one is forced to come to work and we clearly communicate to our team members to stay home if they do not feel well," JBS spokesman Cameron Bruett said.

Little leverage

Much of the meatpacking industry is consolidated under four large companies — JBS, Smithfield, Tyson and Cargill — and the workers don't have much leverage.

Unlike 60 years ago, meatpacking union contracts are plant-specific. Workers in Worthington could theoretically strike, but the owner, JBS, could shift production to another plant or bring in workers from elsewhere.

The union that represents workers at the plant, UFCW Local 663, says it that protecting the workers has been essential to keeping the region's food supply safe.

"UFCW Local 663 has worked tirelessly to advocate for Minnesota's meatpacking workers, securing emergency pay increases as well as critical protective equipment and strengthened benefits to help them support their families during this crisis," the union said in a statement.

It added, "Our country owes a great debt to these meatpacking workers and we will continue to speak out and fight for the protections they need to stay safe as they do these incredibly important jobs."

While most large meatpacking plants have union representation -- Local 663 also represents workers at three other sites in Minnesota -- some do not, including the including the Pilgrim's Pride chicken plant in Cold Spring and the Jennie-O turkey plant in Willmar.

And every plant hires third-party contractors to perform some work, often at lower wages and with fewer benefits. A cleaning worker for PSSI Inc. at the Jennie-O plant in Willmar had no health insurance when she passed out on the job several weeks ago.

An ambulance took the woman — named Mejia, who asked that her last name not be used — to the hospital and an X-ray showed something cloudy on her lungs, leading to a COVID-19 diagnosis. When she returned home, she separated herself from her three children and mother in the house.

"I spent six days in my basement," Mejia said. "They called my son and made him go take a test. He also tested positive. We all got sick."

PSSI paid her for 10 days of quarantine, but otherwise didn't check on her. Of the 105 PSSI employees she works with at the turkey plant, she estimates 60 have gotten sick.

PSSI said in a statement that all of its employees are offered health insurance, the company undertook new measures to prevent infection, and it knows of no "open or pending" cases at the plant in Willmar.

The industry entered mid-March killing animals at record volumes, with approximately 10% growth from a year earlier.

But the idling of dozens of plants, including JBS in Worthington and Smithfield in Sioux Falls, dramatically reduced the nation's hog slaughterhouse capacity by early May. Hundreds of thousands of pigs had to be euthanized because there was no place for them to be slaughtered.

The industry bounced back, in part by running Saturday shifts. On Wednesday last week, 469,000 hogs were killed at U.S. plants, just 2% below the same day a year ago.

The return to work has been difficult for some employees.

Ta Tha Htoo, who works boning hams on the line at JBS in Worthington, returned to work in May after recovering from the virus. But he couldn't hold a knife after the illness exacerbated stiffness and soreness in his right wrist, ring finger and little finger. He had to have surgery.

JBS is paying for the surgery, provided he returns to work, he said.

"This whole thing, it's not worth it," he said. "JBS workers getting hurt, and other companies having people working and getting sick and dying."

Even at JBS, some workers say the union does not have much power.

Hector Alvarez worked at the plant in Worthington for 22 years when a predecessor UFCW local represented the plant's workers. Now he's retired and lives in a trailer park across Hwy. 60 from the plant. His wife still works for JBS.

He said when he started at the plant, under a previous owner 25 years ago, the line speed was manageable. But it gradually increased, and the union could do nothing to stop it.

"The line ran too fast," Alvarez said. "They say 'We'll see, we'll see.' And they didn't do nothing."

People from so many different countries and ethnic backgrounds work at the plant — Mexican, Eritrean and Myanmar natives, for example — that it can be difficult for them to unify, Alvarez said.

"They don't understand each other," Alvarez said. "They can't go together."

The transience of immigrant workers, some of whom work to send money to family in their home country where they hope to return, doesn't help union organizers, said Roger Horowitz, a University of Delaware professor of labor history.

"Those workers are very hard to organize because their framework is temporary," he said.

Gone the next day

Ramirez, the JBS worker, was tested just before the Worthington plant closed on April 21, his wife said. He was positive.

Nobody from JBS checked on him when he was sick, his wife, Maria, said. A friend of his would drop off food at his door.

The day before he died, she spoke with him on videochat. He didn't look good, she said, so far from the energetic, kind man she had met at a dance 30 years ago in a small town in central Mexico. He loved to dance. He was so friendly, she said, so well-liked by everyone. He was a hard worker, who would never miss a shift and would volunteer for every overtime assignment.

When he didn't answer the phone the morning after their video call, she had her son notify the Worthington police. They found him on the floor of his home with no pulse. Unable to gather because of the pandemic, his family held a funeral online.

The only contact JBS has had with anyone from Ramirez's family was to notify them that he had a final paycheck they could claim, Maria Ramirez said.

"I don't feel like it's normal, their negligence," she said. "I wish they would at least send me his ashes."

JBS said it was never in possession of Ramirez's remains.

"We mourn the tragic loss of Mr. Ramirez and extend our condolences to his family and all the families who have lost loved ones during this global crisis," Bruett, the JBS spokesman, said. "Unfortunately, we were not aware of his illness until his untimely passing."

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?