A media coalition wants a federal judge to reconsider the "unconstitutional closure" of his courtroom for the upcoming federal civil rights trial of three former Minneapolis police officers in the killing of George Floyd.

Writing on behalf of local and national media organizations to U.S. District Judge Paul Magnuson on Monday, attorney Leita Walker said the judge's limitations on access amount to a closed courtroom in violation of the U.S. Constitution's First Amendment.

"We do not need to explain to this court the gravity of the trial, the impact Mr. Floyd's death had on the Twin Cities and the world, or the public's ongoing and intense concern for how the criminal justice system deals with those accused of killing him," Walker wrote.

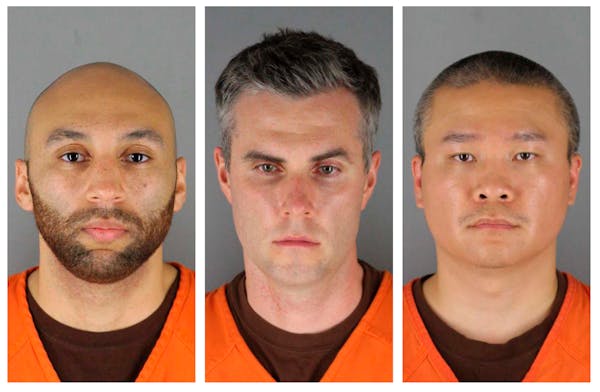

The trial begins Thursday with jury selection at the courthouse in downtown St. Paul in the trial of former Minneapolis police officers J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane and Tou Thao. The three are accused of depriving Floyd of his constitutional rights.

In May 2020, Kueng and Lane helped former officer Derek Chauvin hold Floyd to the ground for more than nine minutes as he begged for his life and said he couldn't breathe; Thao kept bystanders from intervening. Chauvin was convicted of murder in state court last year and pleaded guilty to federal charges last month.

Jane Kirtley, a lawyer and director of the Silha Center for Media Ethics and the Law at the University of Minnesota, a member of the coalition, noted the significance of the case in calling for greater access.

"This is a civil rights case and it's hard for me to think of a more important case for the public to have the opportunity to see as well as hear what's going on," she said, adding that even the U.S. Supreme Court started allowing live audio of proceedings in the past two years.

The conditions for the upcoming trial are a jarring contrast to Chauvin's murder trial last March, which was livestreamed to the world from the Minneapolis courtroom of Hennepin County District Judge Peter Cahill. In the letter to Magnuson, Walker cited the immense public interest in the case as evidenced by the audience of more than 23.2 million who watched as the guilty verdicts were read in Chauvin's case in April.

But the rules are different in federal court, where fewer than 100 will be able to watch this trial. There will be no livestream of the proceedings from Magnuson's courtroom to the outside world.

Instead, a closed-circuit feed from the courtroom will be streamed to two overflow rooms, one for the media and one for the public. Each room can accommodate 40 spectators.

The live feed will be streamed from monitors fixed on four spots in Magnuson's courtroom: the lectern at which attorneys stand, the witness stand, the judge's bench and the evidence. Unlike in the Chauvin trial, the cameras will not pan or zoom. The court has not guaranteed that evidence, including videos, will be discernible to viewers, Walker said.

Also not visible to viewers outside the courtroom: The defense tables or the jurors, meaning that "no one in the overflow room will ever lay eyes on any one of the defendants throughout the entire trial," Walker wrote.

Media — but not members of the public — will be allowed in the courtroom on a limited basis. During jury selection, two members of the media will be allowed in the courtroom. No members of the public or family members of Floyd or the defendants will be allowed.

During the trial, four members of the media and a sketch artist will be admitted as will some family members but not the general public, Walker wrote.

Walker asked that the court "take immediate steps to rectify the situation." She quoted the U.S. Supreme Court's recognition that "to work effectively, it is important that society's criminal process 'satisfy the appearance of justice,' and the appearance of justice can best be provided by allowing people to observe it."

Regardless of the pandemic, Walker said the right to access is not a theoretical one and she referred to Cahill's groundbreaking decision to allow the livestream from his courtroom. During Chauvin's trial, two media seats were provided daily in the courtroom as well as seats for Floyd's and Chauvin's family.

In ordering the livestream of the Chauvin trial, Cahill cited the unprecedented social distancing requirements and space constraints brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In contrast, Walker told Magnuson that he had not "taken every reasonable measure" to accommodate the press' and public's ability to monitor the trial. "Rather, it is effectively closing the courtroom doors in violation of the U.S. Constitution," she wrote. "There are various routes to a more open trial."

The court could move the trial to a larger venue and reduce the number of potential jurors brought in during each session of jury selection to allow for more seats for the public, Walker said. She also urged the court to improve the closed-circuit feed to the overflow rooms so members of the press and public can see what's happening throughout the courtroom and the evidence.

She closed by saying the media is "standing by to assist in any way it can."

Kirtley said access to the proceedings, including evidence such as videos, is critical to public understanding. "These are not our media rights exclusively; these rights flow from the public rights," she said. "When they're closing out the press, they're closing out the public."

Star Tribune Managing Editor Suki Dardarian pointed out that a similar media coalition had partnered successfully with the state courts for the livestreaming of the Chauvin case and could do so again here.

"While we appreciate the federal court's efforts to make adjustments, the fact remains that public access to the trial proceedings and the evidence is less than adequate," she said.

The media coalition includes MPR, the Associated Press, CNN, CBS, Court TV, Gannett, Hubbard Broadcasting, Minnesota Coalition on Government Information, NPR, NBC, the New York Times, Sahan Journal, TEGNA Inc. and the Washington Post.

Magnuson did not respond to a request for comment.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?