Mike Lindell's biggest gamble: Giving hard sell to baseless election fraud claims

Mike Lindell has made countless bets in his life, some that cost him everything he had.

But after the November election, the MyPillow founder made his biggest gamble yet: that he could sell America on the discredited idea that rigged voting machines cheated President Donald Trump out of a second term. Lindell has refused to let up — even after courts rejected dozens of fraud claims — and he visited the White House with notes that mentioned martial law shortly before Trump left office.

A maker of voting machines is now suing him and his Chaska-based business for $1.3 billion, far more money than either is worth. While Lindell says he's made many narrow escapes before, the stakes for him have never been higher.

"I'm living in, right now, the bad part of the movie, but it doesn't bother me at all because of my faith," Lindell said. "I know how this is going to end."

It's the kind of high drama Lindell, 59, has sought his entire life. He chased attention and thrills as a child and became addicted to cocaine, gambling and alcohol as an adult — before finally gaining fame and wealth as the founder of a midsize pillow manufacturer.

Even as he battles a lawsuit that could wipe out MyPillow and his fortune, Lindell is threatening to shake up the Minnesota governor's race with a run next year. For the Minnesota GOP, Lindell is as much a wild card as Trump was for the national party when he burst onto the 2016 campaign scene.

Because Lindell's commercials have been running for years, people feel like they know him. To some, he's a blustering blowhard, an easy target for mocking. To others, he's a courageous crusader, gathering believers along the way.

Those who know him best say he tends to act on impulse rather than following a plan. Lindell says he has premonitions, or "whispers from God." But his election-fraud campaign has mystified friends, worried some MyPillow workers and led at least one director to quit his company's board.

The company suing Lindell, Dominion Voting Systems, portrays his criticism of voting machines as the extension of a strategy begun years ago to lift MyPillow's sales by aligning it on one side of America's culture war.

Lindell calls his fight an effort to preserve the integrity of voting, describing it as another "divine appointment." He says he can't go back to just being a businessman. "That ship has sailed," he said.

For years he has called himself an "open book," and since 2019 has pointed to his actual book — called "What Are The Odds?" — where he describes overcoming drugs, gambling and other personal upheaval.

"He talks in his book about how he was always striving for acceptance," said Jim Furlong, a longtime friend who is president of MyPillow. "He was accepted by the most powerful man in the world. What greater validation is there than that?"

In more than seven hours of interviews with the Star Tribune since Lindell began his election-fraud campaign four months ago, he never wavered in his certainty. And he almost always maintained the affable intensity of his commercials.

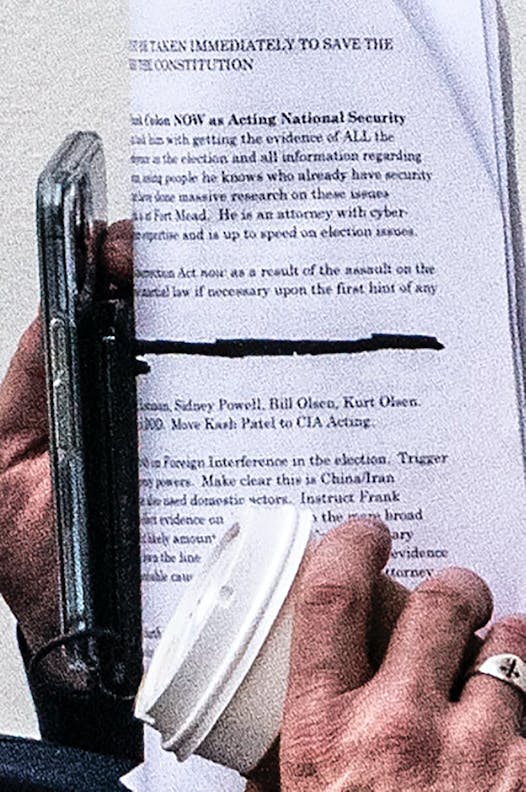

Lindell says he has spent more than $3 million trying to sell that idea, some of it to sponsor postelection protests that culminated in the deadly Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. Lindell sat nearby that day at a rally where Trump delivered a speech largely seen as inciting the mob. About a week later, he returned to the White House with what he claimed was new evidence of election hacking. That evidence, and his notes suggesting martial law, gained no traction.

Now, Lindell's fraud campaign is fizzling and his endgame is getting harder to decipher.

He paid for a two-hour video, called "Absolute Proof," that recycled previously debunked claims and which only one conservative news network agreed to air with broad disclaimers last month.

Afterward, he was surprised the film did not attract a mainstream audience and became irritated when journalists stopped calling. He now says that even conservative news outlets will no longer interview him on live TV for fear he'll get them sued. Lindell declined repeated requests from the Star Tribune to share the original documents that he claims prove fraud.

He hasn't spoken to Trump since that widely covered meeting at the White House. His campaign on Trump's behalf has cost his company MyPillow distributors. And Twitter pushed Lindell and MyPillow off its platform.

But with polls showing a majority of Republicans believe the election results are invalid, the market for Lindell's message is vast. His claims of voter fraud may be getting less airtime, but those ideas are helping bolster Republican-led efforts to restrict voting access nationwide.

Entertain, embellish

Before his surprising kinship with Trump gave him a political profile, Lindell was simply the mustachioed CEO who hugged pillows and described "patented foam technology" on infomercials.

And well before that, he was the longtime co-owner of a bar in Victoria, 30 miles southwest of Minneapolis. In those days, Lindell's addictions and rocky personal life produced two bankruptcies, two failed marriages, another brief engagement and a pattern of domestic disputes that brought out law enforcement.

One former girlfriend alleged multiple violent incidents in 2008, which Lindell denied. That led briefly to a court-imposed protection order against him. They later reconciled.

Lindell admits frequent run-ins with the law earlier in his life. Deep in debt and fearing for his safety in 1983, Lindell says, he botched a gas station robbery and led authorities on a high-speed chase in St. Peter. Lindell also accrued repeat DWIs and spent time in jail.

Lindell's version of his life story features numerous vignettes of coolly standing up to imposing figures, whether in a late-night fight in downtown Minneapolis or with machete-wielding drug dealers in Mexico. Most of these tales end with Lindell talking his way out of danger.

Lindell recalls first showing off to audiences as a child, calling it a defense mechanism after his parents divorced and he changed schools. When he was in fifth grade, he said he jumped out of a school bus window on a dare.

Before giving up drugs and alcohol in 2009, he asked his friend Dick VanSloun, "Is it boring to be sober?" VanSloun, a recovered drug addict who's now a supervisor at MyPillow, says he replied, "Why would it be boring?"

Some of Lindell's friends believe the latest high drama in his life reflects his unending chase for excitement.

"It's like the drama of the politics with Trump and the election being stolen and all that is kind of his replacement for drugs and alcohol," Furlong said. "I mean, you stand up in front of tens of thousands of people, that's very, very addicting."

Because pillow-making is a relatively easy business to enter, success takes aggressive marketing. Chief among Lindell's strengths is as "a promoter of ideas," said Bob Roepke, a former MyPillow board member. Lindell's ease with exaggeration got the company off the ground.

For several years, Lindell claimed MyPillow cured ailments. When a legal challenge by California prosecutors forced him to stop doing that, the company commissioned a deeply flawed study on which to stake its health claims. The prosecutors ended that, too.

Lindell says that MyPillow employs around 2,500 people. But other executives would only say the number of workers at its two production plants: about 700. MyPillow's annual revenue is about $250 million, another executive said, while Lindell often portrays it as much higher.

In 2019, when Lindell launched an e-commerce venture called MyStore, he told the Star Tribune he expected to have 20,000 employees working on it by the end of that year. To date, a handful of MyPillow workers fulfill MyStore orders from a corner of the factory.

MyPillow faced a crossroads in 2014, when sales growth leveled off and it had about $6 million in unpaid bills. Lindell tried something new by putting regular commercials on the Fox News Channel amid midterm election coverage.

The ads featured him talking about MyPillow's small-town roots, a made-in-the-U.S. message that resonated with Fox viewers. Sales grew so much that the firm quickly paid off its bills and socked away $8 million in new profit, according to Lindell. In his book, Lindell claims he predicted the shocking turnaround to board members months before it happened.

In 2017, the Better Business Bureau downgraded MyPillow's rating from an A+ to F, calling its continuous "buy one, get one free" promotion deceptive pricing. Lindell has often suggested it was punishment for his political beliefs.

Foam, cotton and politics

Inside MyPillow's main Shakopee factory, Lindell's image is everywhere. Life-size cardboard cutouts of him snuggling a pillow are propped up at the front door, next to the safety bulletin board and in the shipping office. In one, Lindell's face is decorated with plastic sunglasses and a paper version of a red "Make America Great Again" hat.

Lindell's relatives and friends occupy many top jobs at MyPillow and, though he hasn't been at the office since the election, he's always a call away.

"I do a lot of micromanaging and macro-managing," Lindell said. "It's very hard for us to hire anybody outside of MyPillow from the corporate world, because it's not run right."

Todd Taylor, Lindell's stepbrother and the Shakopee plant manager, is required to alert Lindell anytime something strays from normal, whether a computer server goes down or a supplier misses a delivery.

"Mike can sometimes make things happen. He'll tell you he always can," Taylor said with a chuckle.

Lindell says hundreds of employees have his number and that he urges them to call about any "blocks" and "deviations" in the operation. He applies the same terms to his election conspiracy claims, reminding others of what he calls his special ability to spot anomalies.

In the workplace, he also believes everyone deserves a chance. MyPillow production is handled by people who have criminal records, moms who need flexible hours and non-English speakers with limited job options.

"Honestly, this company saved my life," said Graham Kelley, a production coordinator who spent 15 years in and out of prison on drug and theft crimes. "My girlfriend works here, our cars in the parking lot aren't stolen, and I've got a little money in the bank."

As Lindell doubled down on his fraud claims after the election, MyPillow says its sales rose sharply but the customer base shifted. More than 20 major retailers, including Kohl's and Dollar General, dropped its products. Direct sales to consumers shot up dramatically, lifted by buyers who wanted to show support for him.

In January, Roepke, a former mayor of Chaska, decided to leave the MyPillow board of directors. The two had always shared an interest in giving all people opportunities, but he could no longer reconcile that with Lindell's political rhetoric. "That misalignment didn't seem like a healthy thing," Roepke said.

Doubts and conviction

Around the election, Lindell spent a couple of hours during a flight on his private plane arguing about election fraud with Furlong, a Democrat. "The more you say 'no' to him," Furlong said, "the stronger his commitment becomes."

Furlong, who's known Lindell for 17 years, said he's seen him make mistakes. In 2006, Lindell nearly lost control of MyPillow to two men he described in his book as down to earth. "Sometimes I think Mike puts too much faith in the wrong people," Furlong said.

Linda Donovan, whose brother co-owned a bar with Lindell before falling out with him, said she believes Lindell is convinced of election fraud but she doesn't understand why he's gambling the future of MyPillow on it. "I don't know how that tune can help his business at all," she said.

Lindell was initially surprised MyPillow was roped into the lawsuit. "MyPillow had nothing to do with this," he said. "The only reason they would do that is to scare other outlets and other companies to not talk, or other people to not talk."

But he insists his version of the 2020 election's outcome will bear out in court. "There's only one truth," Lindell said. "So right now I know that truth. I only get this convicted when I'm a hundred percent true. A hundred percent."

In 2014, Lindell met his current girlfriend, Kendra Reeves, through his sister. In his book, Lindell writes that Reeves altered how he thought about the premonitions he experiences, convincing him they had spiritual origins. Today, Lindell is rarely seen without a cross on the lapel of his jacket or on a necklace.

"I was going down a very bad path with my life of addiction … and now I know I'm going down the right path. I'm doing the kingdom's work," Lindell said.

Early in their courtship, the couple befriended the actor and Christian conservative Stephen Baldwin and his wife Kennya, traveling the world together to attend religious events. Through the Baldwins, Lindell and Reeves also gained access to a new inner circle of celebrity faith leaders and the politically connected.

Lindell became an important ally to Trump when the "Access Hollywood" tape imperiled his presidential campaign. When Trump faced calls to drop out of the race, Lindell used his own redemption tale to argue that Trump wasn't the same person who had bragged about sexually assaulting women.

Trump's campaign subsequently asked Lindell to speak at a rally at the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport shortly before the 2016 election. Lindell quickly realized the platform that politics offers to spread his religious message.

He got more chances to speak each time Trump returned for rallies in Minnesota over the next four years. And Lindell has since given at least $360,000 to GOP candidates nationwide. Last spring, Lindell also addressed the country from the White House Rose Garden at one of Trump's coronavirus-related briefings.

When Lindell set out for a walk in Washington the morning after the Jan. 6 Capitol siege, he was by then recognizable to a broader audience than at any other point in his life. As he spoke by phone to a Star Tribune reporter, Lindell paused to take a photograph with a fan of his. Just moments later, Lindell caught someone else's eye. A bicyclist could be heard angrily shouting at Lindell to leave town: "Traitor! You insurrectionist! Get out of here. You're not American."

What are the odds now?

No one looms larger over the 2022 Minnesota governor's race right now than Lindell, early as it is.

Roughly a half-dozen Republicans — most with far deeper backgrounds in electoral politics — are testing the waters. Yet in a sign of Lindell's strength, Minnesota Republican Party Chair Jennifer Carnahan vowed in a post on Twitter last fall that her party would make Lindell the state's next governor. She has since said she can't comment on would-be candidates before the party endorsement. Carnahan's tweet prompted a state senator to challenge her for party leadership this spring. Even the potential of a Lindell run has prompted targeted fundraising pushes by the Minnesota DFL Party and Gov. Tim Walz's re-election campaign in a way no other potential challenger has so far.

Lindell insists that he won't run if the same voting machines are still in use. Minnesota election officials noted that just six counties used Dominion equipment in the election, five of which were won by Trump.

Talk of a potential run for governor gained momentum a year ago when Lindell — by then "honorary chair" of Trump's re-election campaign in Minnesota — declared that he was strongly considering challenging Walz.

Yet multiple state Republican Party operatives calculate that there is virtually no chance Lindell runs. Some question his ability to remain disciplined, others believe the election fraud quest and subsequent lawsuit tank his viability.

"I think it definitely was [a possibility] a year ago at this time," said Amy Koch, a GOP strategist and former state Senate majority leader. "But that was before January 6, 2021, and all of his statements since the elections."

But conventional wisdom has never guided Lindell, and he doesn't sound like a man shutting the door on a run for office. He likes to say he would manage Minnesota as he does MyPillow. And Lindell still sermonizes about what he sees as the shortcomings in Walz's response to COVID-19 and civil unrest.

"One of the things I have an advantage in is I don't have to announce until the very last minute because everyone knows me," Lindell said. "My name is out there."

Lindell is working with screenwriters to turn his 2019 book into a movie. He said he recently called them to insist his fight over the election results — that bad part of the movie that the hero must overcome — be added.

"This has all changed," Lindell said he told them. "This is bringing me to a level that I've never thought God would bring me to."