Mike McFadden stood before a crowd of college students that included backers of his rival, U.S. Sen. Al Franken — some carrying signs that said "Mike McFadden cares more about millionaires than me."

Undaunted, McFadden gave them a nod and flashed an easy grin. "I know there's people in this room that will agree with me. I know there's people that won't agree with me. That's OK," he said, moments before walking toward them, hand extended.

The art of campaigning hasn't come easily to McFadden, an investment banker who has never held elective office, and hadn't voted in a primary in 20 years before his own. Yet McFadden beat out a field of experienced politicians for the Republican endorsement, easily won his primary and gained the backing of Independence Party leaders who chose him over their own primary winner.

McFadden says his great asset is that he's not a politician, nor was he bred to be one. He doesn't need this job, but he wants it.

"You have this professional class of politician that's been created in this country — both sides of the aisle — and its killing us," McFadden, 50, said over coffee in downtown St. Paul. "I have a life that I've developed with my family, with coaching, with my work career. I decided to leave that because I felt a sense of duty to serve."

A lot is riding on McFadden. Republicans lost this seat in 2008 to Franken by 312 votes and with their party narrowly projected to take the Senate majority, a McFadden win could prove vital. Democrats are pushing back hard, attacking McFadden as a corporate chieftain unfamiliar with the struggles of the middle class, who puts profits above people.

In a year of stump speeches focused on his "three E's" — energy, education and effective government — McFadden's message hasn't changed, but his poise and polish have. Early stumbles and policy gaffes — he once said he was for a gas tax increase, then moments later said he was against it — appeared to bode ill for the novice candidate.

To turn things around, McFadden drew on the skills that helped him excel in business. Intense and engaged, he is known as a shrewd negotiator skilled at bridging divides, former business associates say. McFadden parlayed smarts and a strong work ethic into a career that's given him a net worth, according to financial disclosure filings, between $15 million and $57 million.

By the time McFadden met Franken in their first debate, he was ready. He first caught Franken off-guard by thanking him for his service, then pointed out to the crowd that Franken and his wife were about to celebrate their 39th anniversary, leaving a startled Franken to chuckle, "I was going to use that."

Hitting the trail

McFadden's reputation as a fast learner is underscored by the strategy and evolution of his campaign.

"I think I can best describe him by observing what has happened in the last six months," said Bert McKasy, a friend of McFadden's and a former GOP state legislator who twice vied for the U.S. Senate nomination and lost. "He's got no political experience, he moves in and sort of steals the political endorsement from some pretty experienced politicians," McKasy said.

McFadden has courted voters in all 87 of the state's counties. Slowly he's won over skeptics in his own party who doubted whether a rookie — even a well-heeled one — was ready for the grueling endurance contest that is a U.S. Senate race.

He hasn't converted everyone. McFadden avoids divisive social issues, often steering questions back to his talking points. He doesn't embrace the moderate label, but doesn't object to it. He still has a pronounced tendency to shy away from specifics on many issues that has alienated some.

"Here's my position with Mike right now. I have no idea what he represents, and I don't expect promises from politicians, only a covenant, and he has not made one covenant with the people," said Jack Rogers, president of the Minnesota Tea Party Alliance who says he's undecided, but unlikely to vote for McFadden. "I think the people driving his campaign overlooked principled voters."

'Learn, earn, serve'

The eldest of four boys and a girl, McFadden grew up in a rambunctious Omaha household. Vernon McFadden, an IBM engineer, and Mary McFadden, a teacher-turned-homemaker, were protective of their close-knit, devoutly Catholic clan, though with five children close in age, the house hummed constantly with happy discord, said McFadden's sister, Kathy Kazor.

"It was your typical Irish Catholic family," Kazor recalled. "Family was first and it was crazy. I can always picture my mom with her wooden spoon saying, 'Stop it, boys!' I think she broke one of those on Mike's behind."

McFadden went from Creighton Prep to the University of St. Thomas, where he played football and graduated magna cum laude with a degree in economics. He got his law degree at Georgetown Law School and studied at the London School of Economics.

After passing the bar, McFadden joined Cravath, Swaine and Moore, a prestigious New York law firm. In 1993, eager to return to Minnesota, he contacted Jack Helms, chief executive of the Minneapolis-based boutique investment bank Goldsmith Agio.

When McFadden was hired, Goldsmith had a staff of about a dozen people, advising on business deals involving small to midsize companies. By the time McFadden became co-chief executive in 2007, the company had grown to more than 90 employees. That year it was acquired by Lazard Ltd., one of the largest investment banks in the world and renamed Lazard Middle Market.

At Lazard McFadden applied his economics training, advising companies looking to expand or sell their firms. At Goldsmith, Helms said, "We did all sorts of things but basically stood between two people who had different objectives. The goal: Listen, get the facts right, develop common ground and forge a compromise.

"Mike was one of the best people at this I've ever met," Helms said. "He is one of the brightest guys I've ever known."

Paul Grangaard, chief executive of Wisconsin-based shoemaker Allen Edmonds, said McFadden's involvement as a board member helped the company regain its footing during the economic downturn. "The business was in turmoil and needed to be stabilized and turned around," Grangaard said. McFadden, he said, advised them on creating a stronger management team and focused heavily on improving the company's product line. He insisted the company continue making its shoes in Wisconsin, even though labor costs would have been cheaper if those operations were moved abroad.

"In a financial crisis, everything's on the table," Grangaard said. "With Mike's support, we never wavered from staying with our U.S. production." Since then, he said, Allen Edmonds' revenues doubled and it now employs more than 1,000 workers. It also has won praise for its quality craftsmanship — a major selling point for Chinese consumers who often spend big on American brands.

Grangaard said he'd like voters to see more of the McFadden he knows. "I would encourage Mike to be more specific about the solutions to our issues. The Mike I know is very smart … I think he can be more upfront with the voters about what he would do differently."

McFadden said his business career has prepared him for Washington under what is called a "learn, earn and serve" model.

"Companies hired me not because I rolled over, but because I advocated zealously for my client with a lot of integrity," he said. "I was ultimately able to bring parties together and reach a transaction. It's sorely missed in Washington — the art of dealmaking. … I think politics is the art of the possible, not the art of the pure. … This mind-set of 'It's not my fault, I can't get anything done because I don't have control'? You're not supposed to control it. It wasn't designed that way."

The Franken campaign and political action committees have sought to disparage McFadden's business record, taking aim at McFadden for Lazard's role in "inversion" or companies that move overseas to avoid U.S. tax rate. McFadden denies allegations made in a recent Franken ad about Lazard's role in selling a small pharmaceutical company to a larger one that later relocated to Ireland. McFadden maintains Lazard has no operational role in the companies, that it only facilitates the sales.

Working the voters

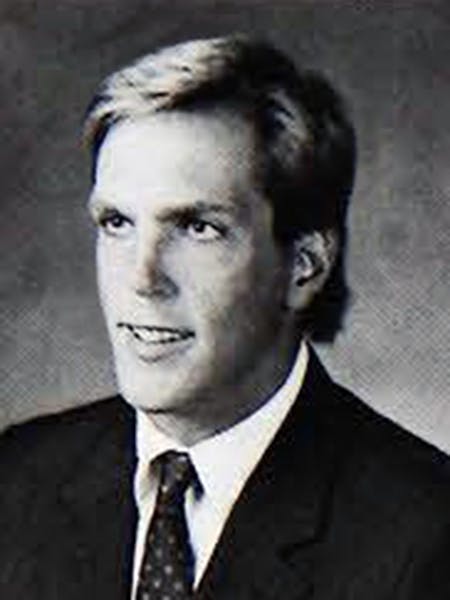

Tall and lean with an intent gaze from deep-set eyes, McFadden provides a striking presence whether delivering his pitch to thousands of Republican delegates or the average undecided voter. On the campaign trail, he typically sheds his suit and tie for a plaid shirt, denim jeans and loafers.

Right after winning the August primary, McFadden started prepping for one of a state candidate's most intense, exhausting experiences: The Minnesota State Fair, where 1.8 million visitors storm the grounds over 12 days to soak up sun, grease, food-on-a-stick — and politics. In a ritual as old as the Fair itself, candidates use the event to shake hands by the thousands and give average Minnesotans a chance to take their measure.

On one hot, damp day at his fair booth, McFadden stood at the head of a long line led by retired real estate agent John Folta, who was eager to talk over the nation's lingering debt crisis with McFadden, who listened intently. Folta walked away unimpressed.

"He's the first Republican in my lifetime, notwithstanding Richard Nixon, that I'm unable to support," said Folta, 64. "I think he speaks in glittering generalities. I hear a lot of 'Well, I'm gonna go to Washington and break the gridlock,' but I don't hear any real concrete solutions."

Next up was Dan Tabor, of Duluth. The two commiserated over a do-nothing Congress. "You know what drives me nuts? No one takes responsibility. This lack of leadership is what's killing this country," McFadden told Tabor, who asked McFadden what he would do. McFadden said he'd bring both sides together to expedite energy projects like the Keystone XL pipeline. "I'm tired of it," McFadden said. "You need to be tired of it. Spread the word."

Tabor came away leaning toward voting for McFadden. Tabor said he found his newcomer status appealing, and like so many others, he is frustrated with Washington. "It just goes on and on," Tabor said. "Both parties are saying what we need to do, but neither side is doing it."

Staying grounded

Amid the grueling campaign, football brings a sense of normalcy for the McFadden clan.

On a recent fall night, Mary Kate McFadden cheers as her youngest son Danny, 11, runs back another kickoff for a touchdown. McFadden pumps his fist as the celebrating offense returns to the sideline. Danny is one of five McFadden boys. The couple also have 18-year-old Molly, whom McFadden likes to call "a rose among thorns." Molly McFadden likes to take selfies with her father on the trail, plastering one wall of campaign headquarters with them. Their oldest, Conor, is a senior on leave from Stanford University to help his dad — whom he affectionately calls "Big Dog" — as the campaign's outreach director.

Mike McFadden taps Danny on the helmet. "Good job, bud," he said. The game is a bittersweet one for McFadden, marking his 14th and final year coaching youth football as Danny heads to junior high school next year.

The evening's game was one of few glimpses allowed into McFadden's personal life. Despite his run for public office, the McFaddens remain private people. A campaign staffer said a visit to the family's large, semi-secluded Sunfish Lake home was off-limits, calling it their "sanctuary."

Mary Kate, who has made only a handful of campaign appearances alongside her husband, said she worried at first about McFadden's Senate run, concerned about the impact on their younger children.

"We decided that we have to do it for our kids," she said. "We have to make a difference for them, to model a behavior that we care and want to show them that it's easy to sit around and talk about things. You have to act."

A stay-at-home mom, Mary Kate said she's unsure whether she'd move the kids to Washington if her husband defeats Franken.

"We haven't gotten to that point yet," she said. "We've got to — we're gonna — win first."

Abby Simons • 651-925-5043

Ricardo Lopez • 651-925-5044

Fact check: Walz and Vance made questionable claims during only VP debate

In Tim Walz's home city, opposing groups watch him debate on the national stage