Why did Minneapolis' famous flour boom go bust?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

It has been nearly a century since Minneapolis was the flour milling capital of the world. But that industrial achievement, which lasted 50 years, remains a major point of pride in the "Mill City."

High school student Nick Zylstra learned about the city's flour milling prowess in a Minnesota studies course. But he was left wondering: What happened? He sought answers about why the flour boom didn't last from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project.

The basic answer is that, by 1930, transportation, tariffs and other factors made it more cost-effective to mill and ship flour from other cities — particularly Buffalo, N.Y. But milling giants that were born on the Minneapolis riverfront, such as General Mills and Pillsbury, continued to prosper by investing in mills elsewhere.

"All of the things that were [Minneapolis'] advantages were slowly eroded over time," said David Stevens, site manager for the Mill City Museum, which is owned by the Minnesota Historical Society.

Becoming the Mill City

Before widespread electricity, Minneapolis became an industrial hub because factories ran their machines using water power from the natural elevation drop in the Mississippi River at St. Anthony Falls. As early as the 1840s, sawmills took advantage of that power to process tree trunks that had been floated down the river from forests in northern Minnesota.

Flour milling posed challenges, however.

The hard spring wheat grown in Minnesota features a tough exterior that shattered when milled using traditional methods, Stevens said. The resulting flour was speckled brown and would spoil quickly, because of the oil in the germ. So flour millers in southern Minnesota began experimenting with a more gradual reduction process to extract the bran and the germ, he said, leaving just the white endosperm.

"Once they figured out how to do that, the hard spring wheat flour was really the best bread flour in the world," Stevens said. These methods were ultimately adopted by millers at Minneapolis' riverfront, resulting in what he calls a "democratization" of white flour — once considered a delicacy enjoyed by European aristocrats.

"Not everybody could afford that," Stevens said. "It was a combination of cheap energy and this new technological revolution that kind of made this available for a mass market."

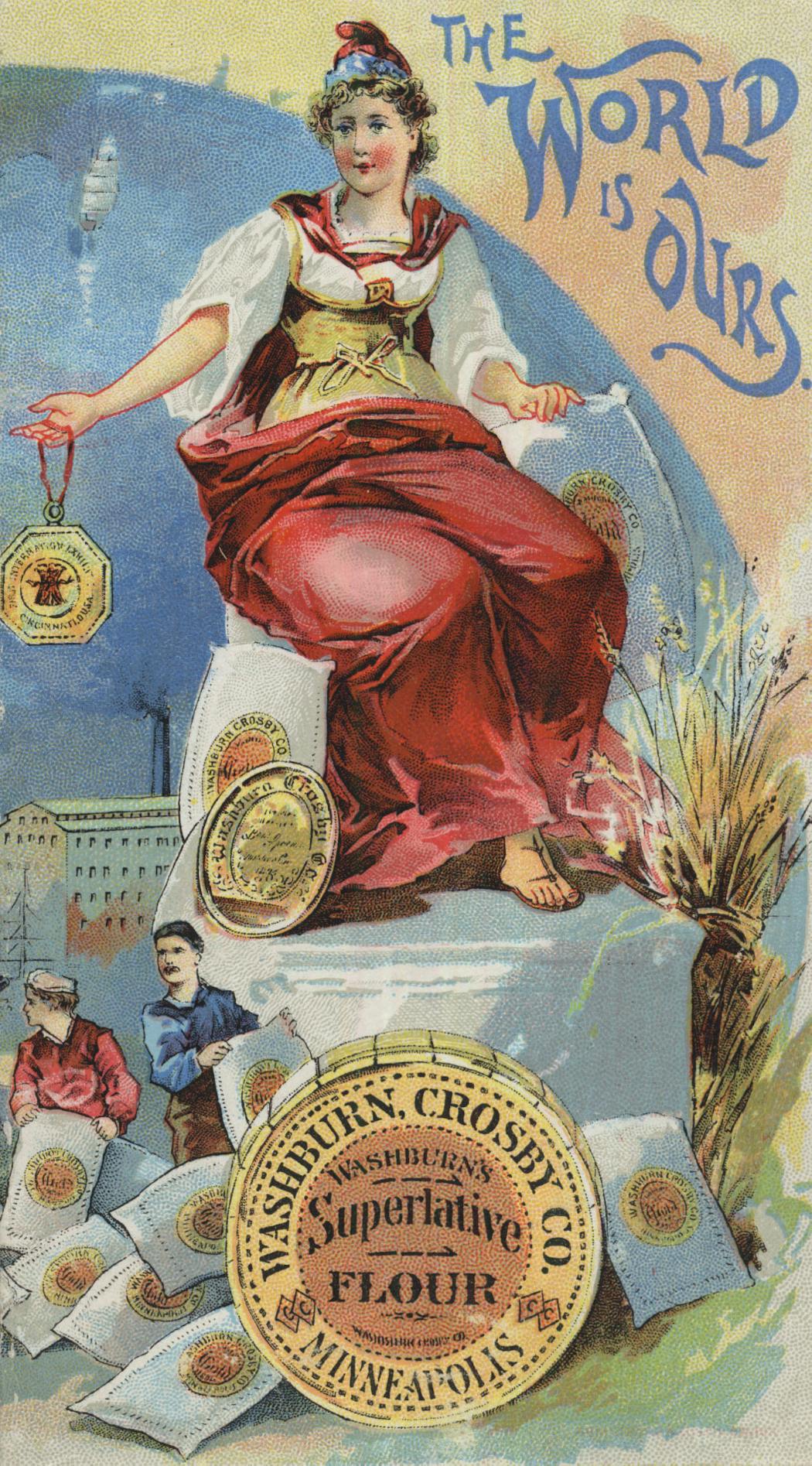

The expansion into European markets around 1880 made Minneapolis the world leader in flour milling, he said.

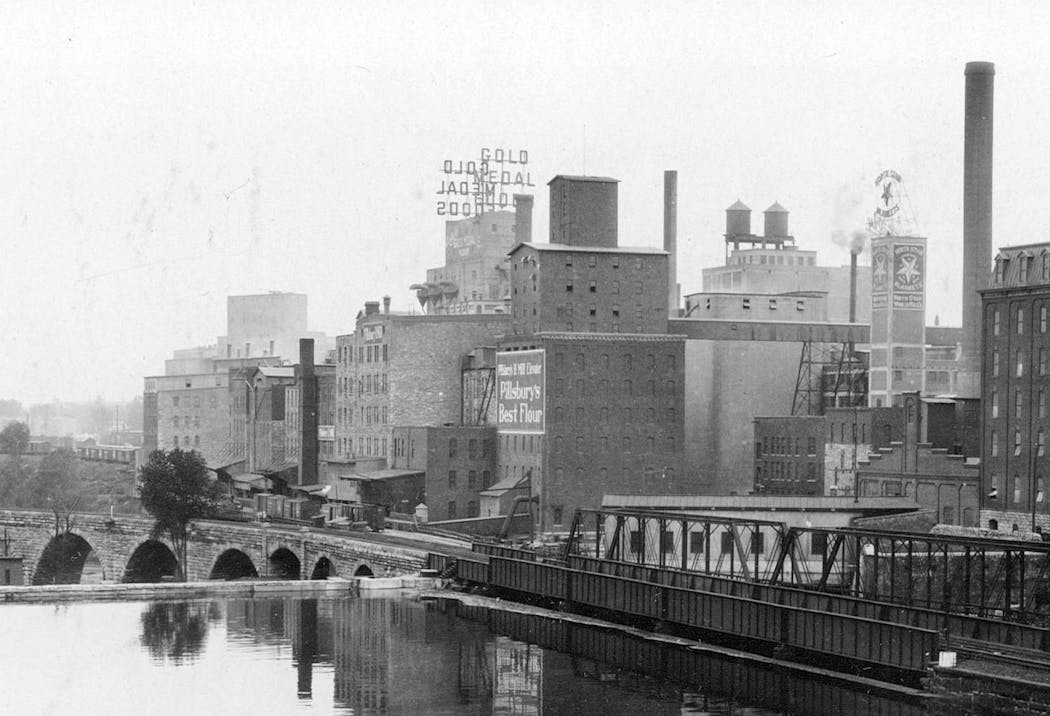

It was boom time for Minneapolis. The city's population nearly quadrupled in the decade after 1880. Washburn Crosby Co. — now General Mills — and Pillsbury Co. opened what were then the world's largest flour mills in 1880 and 1881, respectively, located on the riverfront. (One is now the Mill City Museum, and the other contains apartments.)

Minneapolis' flour output shot up from 7 million barrels in 1891 to more than 20 million barrels at its peak during World War I in 1916, according to a 1929 history of U.S. flour milling by Charles Kuhlmann. Just one of these barrels was the equivalent of 196 pounds of flour.

'Robbing this city of its greatest prestige'

There is not one simple explanation for why Minneapolis lost its flour milling title. The decline was the result of several factors, as outlined in a summary compiled by the Mill City Museum.

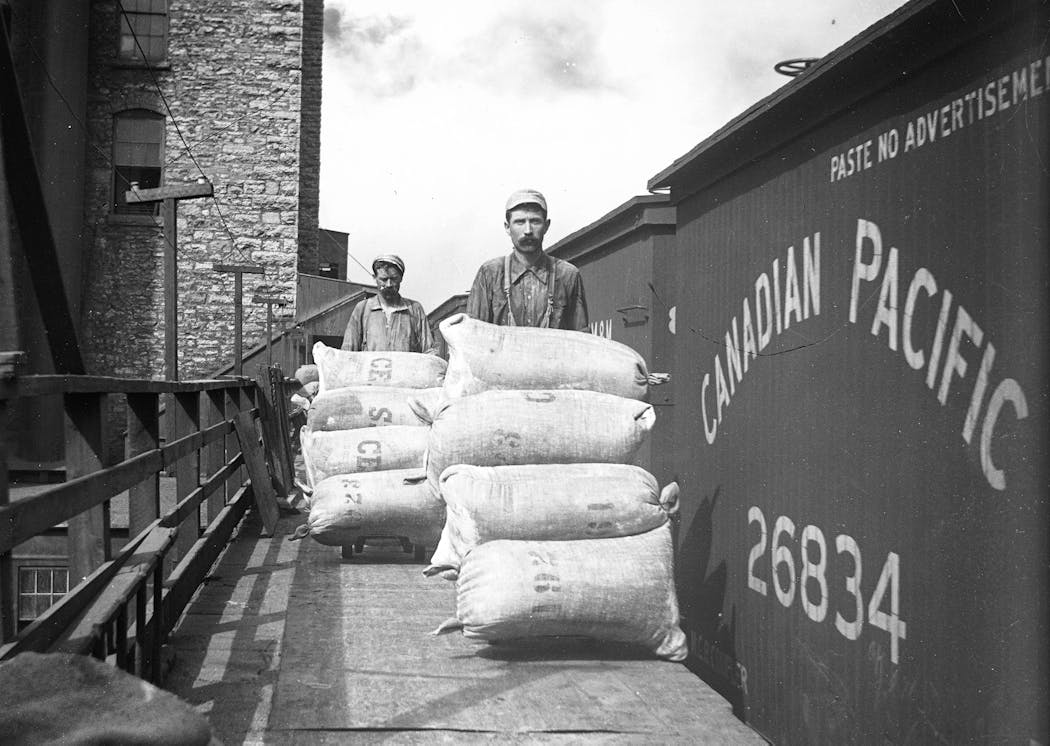

First, it simply grew more expensive to ship flour from Minneapolis compared with other cities. Kuhlmann's history explains that "special favors from the railroads" had helped Minneapolis millers grow their empire. The Interstate Commerce Commission, which regulated freight rail rates, wiped away some of those advantages starting in the early 1900s.

Minneapolis had enjoyed lower rail rates as a result of the competing Mississippi River trade route, for example. But the commission did away with that in 1922. Millers had also paid a cheaper rate on their flour shipments because it was considered wheat making a stop en route to its destination. The commission eliminated that in 1920, forcing them to pay the higher rate for flour shipments.

When Washburn Crosby announced it was building a new mill in Buffalo in 1903, the company's president told the Minneapolis Tribune that freight rail congestion was hindering shipments to the eastern markets.

"Of course Minneapolis is and will remain the dead center of the world's milling," James S. Bell told the paper.

The city of Buffalo benefited from its location. Grain shipments from ports like Duluth could reach it via the Great Lakes, and processed flour could travel easily to the East Coast and international markets.

Because of this, Buffalo also benefited more than Minneapolis from an 1897 tariff change that allowed Canadian wheat to be imported, milled and exported duty-free, according to the museum's summary.

Meanwhile, other wheat varieties began to compete with Minnesota's prized hard spring wheat in the early 1900s. And the advantages of cheap water power were diminishing by the day because of technological advancements.

"Buffalo is becoming the greatest flour-milling center of the world, thus robbing this city of its greatest prestige and the reason is — freight rates," H.G. Benton, secretary of the Minneapolis Real Estate Board, proclaimed in 1925, according to the Minneapolis Star.

In 1930, Buffalo produced more flour than Minneapolis — ending the Mill City's half-century dominance over the market. Kansas City also rose to prominence as a milling center. Pillsbury and Washburn Crosby invested in mills at or near both locations.

"Buffalo was the main competitor, but no city would again dominate the industry like [Minneapolis] did from the 1870s to about 1915," historian Bob Frame, who is writing a book about milling in Minneapolis, wrote in an e-mail. "Buffalo really didn't become the 'Mill City' like [Minneapolis] was the Mill City."

An industrial legacy

Milling at the Minneapolis riverfront ultimately faded away (with the exception of a Pillsbury plant that kept operating until 2003). Lumbermen ran out of white pine for sawmills around 1910, Stevens said. Many of the riverfront flour mills were razed in the 1930s, Frame said.

"That left the [Minneapolis] milling district at St. Anthony Falls not much different from where it is today, with five mill structures left," Frame wrote.

Patrick Ryan, who oversees education and programs for the Buffalo History Museum, said that Buffalonians are very proud of the area's role in milling history. Grain elevators still pepper the waterfront, he said, some of which have been repurposed into art installations.

"Larger grain and milling structures in the area and what to do with them has been hotly debated in recent years, with most residents pushing for historic landmark status," Ryan wrote in an e-mail. Among those structures, currently the subject of a court fight, is the 1897 Great Northern Elevator, which was owned by Pillsbury Co. for several decades.

The city is also home to a massive General Mills plant that produces Cheerios. "My city smells like Cheerios" products are popular in local shops, Ryan said, and even the local visitors bureau promotes the expression.

The present day milling industry relies on a smaller number of larger mills, Josh Sosland, editor of Milling & Baking News in Kansas City, Mo., told the Star Tribune in 2019. Where they are located is based increasingly on the proximity to major population centers, he said, versus the location of an abundant wheat supply.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why does the Stone Arch Bridge cross the river at such an odd angle?

Why did Minneapolis tear down its biggest train station?

How did Nicollet Island become parkland with private housing on it?

Why don't farms water their crops at night?

Why do Minnesotans have accents?

How did Minnesota get its shape on the map?