For much of the 20th century, the Minneapolis Fire Department was a symbol of racial inequity. In 1971, it had been 27 years since the last Black firefighter had been hired — and he was fired for wearing a blue rather than a gray shirt to a fire.

But 50 years ago this month, the city's discriminatory practices took a direct hit with U.S. District Judge Earl Larson's order to desegregate the all-white department.

"It was a big win for the reinstatement of job opportunities and civil rights," said retired Hennepin County District Judge LaJune Lange. As a paralegal, Lange, who is Black, worked on the lawsuit brought by the Minneapolis Legal Aid Society that went before Larson.

PUBLIC FORUM

A public forum will be held this week on the 1971 federal court ruling to desegregate the Minneapolis Fire Department, along with an update on efforts to get historic designation for the city’s former Fire Station 24 where Black firefighters served.

When: 6:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 23.

Who: Panelists include retired Hennepin District Judge LaJune Lange and firefighters hired after the 1971 federal court decision.

Register by clicking here

Today, 31.4% of the department's 414 sworn personnel are people of color — including Bryan Tyner, who last fall became Minneapolis' second Black fire chief.

A few months before the Legal Aid Society filed the lawsuit in 1970, the city's Civil Service Commission had begun considering a change in standards for firefighters to make more minority applicants eligible. Fire Chief K.W. Hall blasted the commission in a memo to all fire personnel: "For your information, I am opposed to lowering any of our standards or requirements. We have a good department that I am proud of and I want to keep it that way."

Larson's landmark decision in the case, known as Carter v. Gallagher, came the following year. The Civil Service Commission sought to overturn the decision, taking the case to the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. When that court largely sustained Larson, two commissioners appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Minneapolis Mayor Charles Stenvig supported the appeal; the City Council opposed it, along with the only Black Civil Service commissioner, Gleason Glover.

The Supreme Court declined to hear the case, and Larson's order stood. The fire department — which in 1972 numbered 544 firefighters, all white — hired 10 people of color: four of them Black, four Native American, one Hispanic and one Asian.

Retired District Judge LaJune Lange, seen at Fire Station No. 4, worked on the lawsuit as a paralegal. Photo by Aaron Lavinsky.

'Kind of unbelievable'

Among them were Mike Beaulieu, Wayne Brown, Skypp Lee and John Wong, who were interviewed this month by the Star Tribune.

Beaulieu, a Chippewa, said he was in a Franklin Avenue bar when two firefighters came in to hand out applications for jobs with the department.

"I didn't think I'd get hired," he said. "We went down to the city all the time trying to get jobs and we were never hired."

But he took the physical and written tests, and got the job. "It was kind of unbelievable," said Beaulieu, now 72. He worked for the department for 30 years, retiring in 2001.

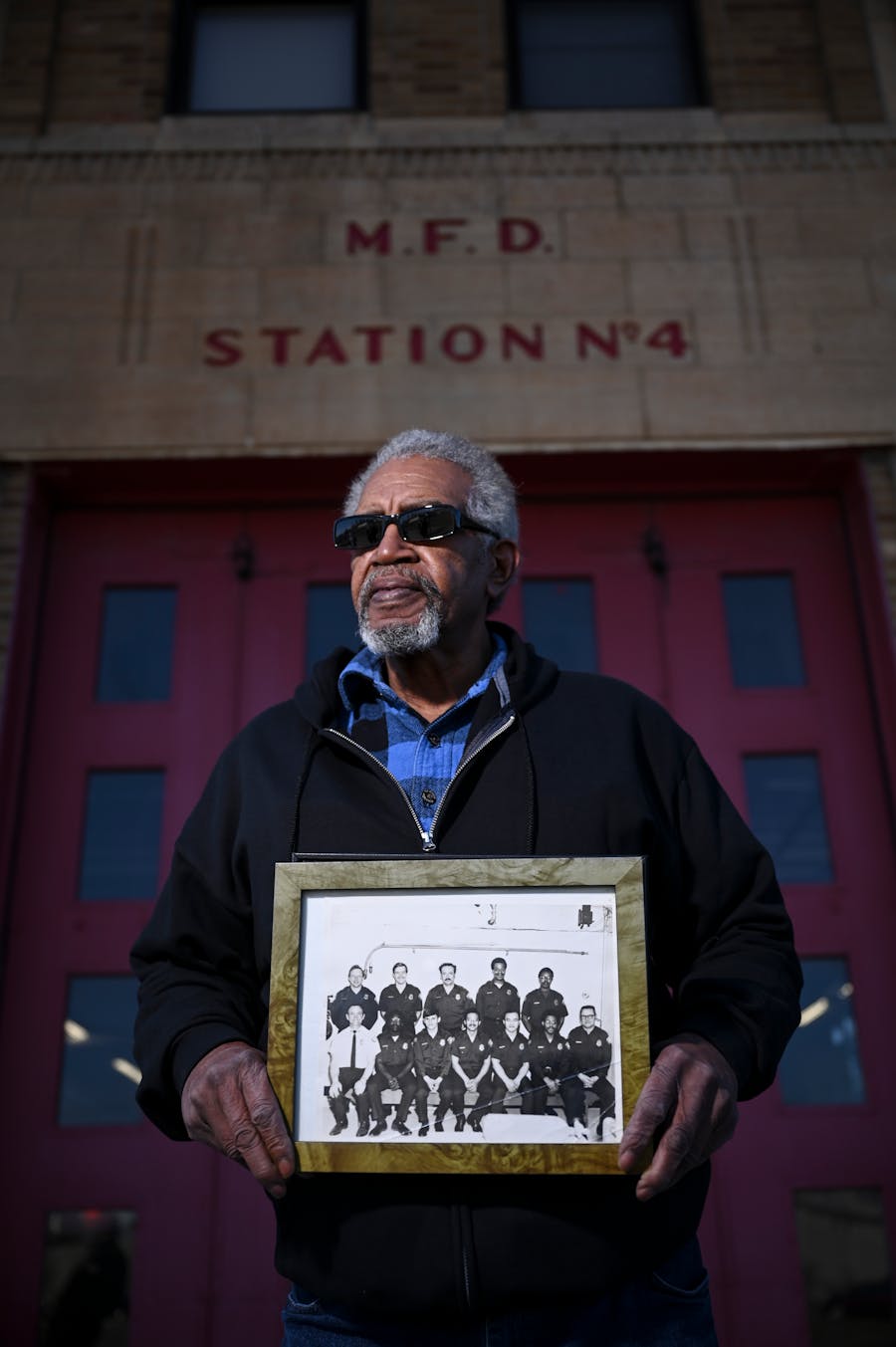

Brown, who is Black, was 28 when he got the phone call that he'd been hired. "I thought it was a bogus call," he said. "It was the best thing that ever happened to me."

"The first time I applied to the Fire Department I was turned down and told that they weren't hiring Blacks until they had to," said Lee, also Black, who was 20 at the time. "I was stunned. I turned around and walked out, my mouth open."

But when the city announced it was hiring minority firefighters following the court decision, Lee took the tests and was hired. "I was pretty damn happy," he said. He retired after 28½ years.

Wong was working room service at a hotel when he was hired by the department. "It worked out really good for me," said Wong, who later became a fire investigator. "I think I was the first Asian hired by the department."

Sparking an uproar

Black men worked for the Minneapolis Fire Department going back to the 19th century. John Cheatham was among the first Black firefighters when he was hired in 1888, and rose to captain.

But after more Black men were hired, Fire Chief J.R. Canterbury assigned them in 1907 to a Black-only fire station because, he said, "No white men will wash in the same bowl and sleep in the same beds with the colored men." Some neighbors opposed having Black firefighters at the station.

Over time, minority firefighter numbers dwindled. When Payne Calhoun was hired in 1944, he was the department's only Black firefighter. But he was fired by Fire Chief Earl Traeger for wearing a blue rather than a gray shirt to a fire.

"Calhoun said during World War II the exact shade of gray shirt was impossible to get because of requisitions by the Navy," said Lange, who interviewed him for the Legal Aid suit.

The firing caused an uproar. Minneapolis Alderman W.A. Hoppe denounced Traeger, saying he had visited nine fire stations and found gray-shirt violators in all of them, the Minneapolis Star Journal reported.

When the City Council threatened to suspend Traeger and demanded he rescind the termination, Calhoun was reinstated. But the firefighter decided not to go back.

Calhoun "said the rumors were that he would be fighting a fire and that his colleagues would not back him up and he would die of smoke inhalation," Lange said.

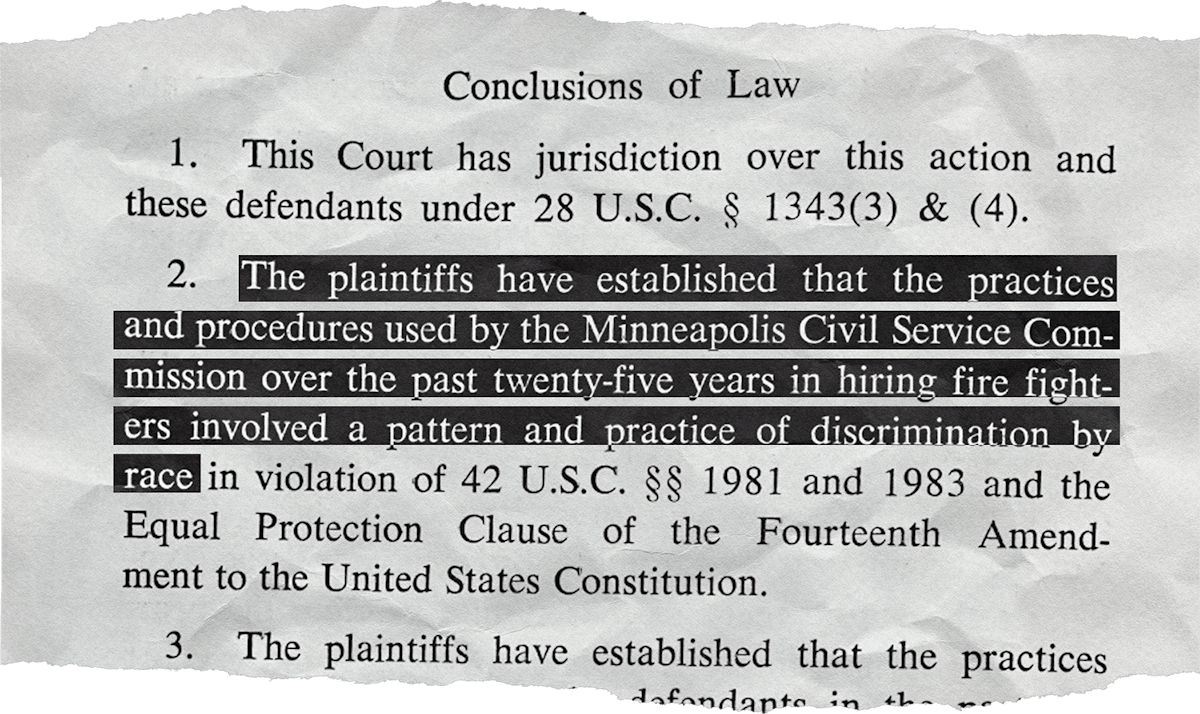

Taken from U.S. District Judge Earl Larson’s order to desegregate the all-white department.

Applause in court

Matthew Little moved to Minneapolis in 1948 and applied to be a firefighter. He had high scores on his written and physical tests, he later told author Jerry Abraham, but was rejected after interviewing with three fire captains.

Little sought out one of the captains after the interview for an explanation. The captain told him that firefighting was a buddy system where men work, eat and live together, and that Little wouldn't fit in. "I just don't think it would work unless we have an all-Black fire department," he told Little.

It so frustrated Little that he plunged into civil rights work and became president of the Minneapolis NAACP. His account was cited in the Legal Aid Society's lawsuit.

A subcommittee of an antipoverty group led by two Black men — Randy Staten, who later became a legislator, and Fred Herndon — supported the Legal Aid suit. Herndon signed up as a plaintiff 22-year-old Benjamin McHie, who told Legal Aid he'd decided not to apply for a firefighter job because he felt his chances were slim since there were no Black firefighters.

Today McHie is founder and executive director of the African American Registry, which does anti-racism work in K-12 schools. "I've come from a family of proud Black people that understood racism," he said in a recent interview.

While litigants said the written tests were not intentionally biased, Elisabeth White, a civil service supervisor, testified in the case "that they may very well be culturally biased." White, now 90, said that city officials didn't like how she testified and transferred her, so she left the city to become human resources director for the University of Minnesota hospital.

Luther Granquist, the Legal Aid attorney who filed the suit, said that at the trial's end, Larson said he'd take the matter under advisement — then looked up and added, "I am inclined to grant the request for minority preference."

"I recall it vividly," said Granquist, now 82. "There was some applause in the courtroom."

Larson's decision didn't mince words. He wrote that the Civil Service Commission's hiring practices showed "a pattern and practice of discrimination by race" in violation of federal law and the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

Former Minneapolis Firefighter Wayne Brown held a photo of the minority firefighters with their trainers after they were hired in 1972. Photo by Aaron Lavinsky.

Laying a foundation

Civil rights activist Spike Moss said Little called together a group of young Black activists — including himself, Bill Smith and Ron Edwards — to urge them to recruit Black people to apply for the department. Edwards was later named by the district court to chair a citizens' oversight committee to ensure the department adhered to the decision.

Larson ordered some preferential hiring for minorities and modified eligibility requirements — but it wasn't over yet.

"Pretty much every time there were hirings, the city screwed up and violated the order," said Legal Aid attorney Rick Macpherson, who later handled the case.

Rick Campbell, the first president of the Minneapolis African American Professional Firefighters Association, sued the department over promotions. "There were no men of color in upper management, let alone fire captains," he said.

The case was settled with the promotion of five people of color, and Campbell himself rose to become the department's fire marshal and deputy chief.

When he was hired, Beaulieu said, some white firefighters would not sit at the same dinner table with him in the firehouse. But others were supportive.

Alex Jackson became the city's first Black fire chief in 2008 and served four years. Tyner, the city's second Black fire chief, met last week with four of the retired firefighters who desegregated the department in 1972.

"I know all of those guys," said Tyner. "They not only laid the foundation for me, but mentored me in my formative years."

Staff librarian John Wareham contributed to this story.

Correction: In an earlier edition, one section of this article misstated the shirt color that led to the termination of firefighter Payne Calhoun. Calhoun was fired for wearing a blue rather than gray shirt to a fire.

Correction: Previous versions of this article misstated the color of shirt Payne Calhoun wore.