Tim Bildsoe helped shape suburban growth for nearly two decades as a member of the Plymouth City Council. Now he recruits couples to join him in a very different boomtown: Minneapolis' North Loop.

"I don't cut the grass anymore, although I'm really good at it," said Bildsoe, who moved into a condo two years ago and is now president of the North Loop Neighborhood Association. "It's really nice to kind of give up those things."

Instead of mowing the lawn, he strolls the downtown riverfront, like thousands of other new residents of Minneapolis and St. Paul — cities that for decades struggled to keep pace with the growth of suburbs around them. Not anymore.

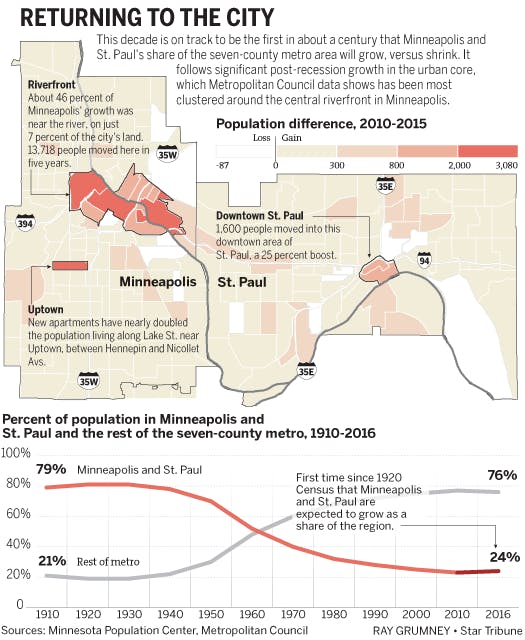

This decade, for the first time in a century, the central cities' share of the metro area's population is on pace to grow instead of shrink, a stunning reversal that long seemed unlikely. The shift has affected the downtowns in particular, as new housing, businesses and attractions reshape neighborhoods once dominated by warehouses, parking lots and railroad tracks.

Minneapolis has added 37,000 new residents since 2010 — already more new people than any decade since the 1920s — spurring the largest population increases along the Mississippi riverfront and in Uptown, areas stacked with new luxury apartments and condos. St. Paul has added 19,000 people in that time, with downtown as the epicenter of the city's otherwise more even growth.

The influx of people is propelling other changes, especially around downtown Minneapolis: a reopened elementary school, new health clinics, a third new grocery store on the way. It's also brought growing pains over limited parking and demands for other necessities, such as more affordable housing, parks or even just a hardware store.

"In the '80s, when I moved to Minneapolis, you did not come over to this neighborhood," said Joan Wright, who now runs Mill City Commons, a group that connects seniors living along the riverfront. The change, she said, is "really truly remarkable."

Now downtown Minneapolis is home to nearly as many — or perhaps more — people than it was in 1950, the city's peak population year, according to an analysis by the Minneapolis Population Center at the University of Minnesota.

Almost half the population gains from 2010 to 2015 have been concentrated on just 7 percent of the city's land along the river from the North Loop to the Mill District to the University of Minnesota, according to the most recent Metropolitan Council estimates. That riverfront area growth represents about 14,000 people, the population of Robbinsdale or Brainerd.

The city's growth looks set to continue. Minneapolis issued permits for more housing units last year than the next five metro-area cities combined.

And not all U.S. metro areas are growing this way. Just 24 of the country's 53 largest metro areas have had central cities grow faster than the suburbs since 2010, according to William Frey, a demographer with the Brookings Institution. That's a shift from the previous decade, when there were just a handful.

"You have young people who aren't able to get mortgages … and that's what you need to buy a suburban house," Frey said. "They've been putting off having families; that's also been correlated with moving to the suburbs."

Attracted to activity

Census data indicate that adults under 30 have been the biggest driver of central city growth, a large portion of the new arrivals are foreign-born, and slightly more people arrive from elsewhere within Minnesota than from out of state. And some of the riverfront growth is due to moves within the city; Wright said many of her members relocated from elsewhere in Minneapolis.

Some of the desire for urban living has been driven by millennials, like Ryan Lambrecht, who want to live in neighborhoods that don't require a car to get around.

Lambrecht works in Brooklyn Park but lives in the Elan Apartments in Uptown. Most of his needs are a short walk away, and his $1,400 a month rent gives him access to a gym and three pools in different buildings — where the crowds range from frat parties to family gatherings.

"One of the huge benefits that keeps me loving this area is just walking everywhere," Lambrecht said.

Lori Nelson revels in the activity she sees in St. Paul's Lowertown, where she sometimes peeks into a local cafe to admire musicians when she's walking her dogs.

"You get a view that you can't get when you're sitting at one of the tables," she said.

Some families have been drawn to the riverfront by the proximity to restaurants and shops.

"I'm a big proponent of not driving," said Michaella Holden Kalan, a Northfield native who moved to the North Loop from New York City with her husband two years ago.

Downtown Minneapolis has enough kids that families persuaded the school district to reopen Webster Elementary, just across the river, in 2015. But the neighborhood isn't quite complete.

"What I would love … is a drugstore," Holden Kalan said of the North Loop, pushing her newborn son, Connor, in a stroller. "A CVS or a Walgreens. We have everything else, pretty much, at our fingertips."

Families also struggle to find affordable housing with space for raising kids, said Eric Laska, who lives in a condo near the Stone Arch Bridge with his wife and three children. A three-bedroom condo or townhouse in the downtown area is a rare find, he said, and can cost $400,000 to $500,000 or more.

"I think families will stay downtown until their kids go into kindergarten," Laska said. "And then they realize that … the endgame is, 'I'm not going to be able to have two teenagers in my condo downtown.' "

What's crowded out?

The growth has a downside.

In Lowertown, artists who created studios in formerly undesirable industrial buildings have had to move amid redevelopment.

Danielle Wang, a physician who moved to Lowertown from Montana last year, realized how the neighborhood had gentrified while speaking with some homeless people in Mears Park. Some of them used to squat in nearby buildings but have been pushed out by the redevelopment.

"Right now there's still that dichotomy of people being moved out, unfortunately, and people moving in to places recently redone," Wang said.

Businesses in Minneapolis' North Loop are coming under additional pressure, too.

Above the Falls Sports, which leads excursions on the river, recently scrambled for new space with reasonable rent after its building was sold to a developer and real estate firm eyeing it for renovations.

"So many people are coming in that you can raise the rent and you'll still find people to live there or work there," said manager Stephanie Vahler. They found a spot around the corner, but "it was really stressful for a while."

Other businesses complain customers have nowhere to park as new buildings replace parking lots. The Alliance Française had been raising money to renovate its building on N. 1st Street, for example, but recently announced it would have to move, partly due to the parking crunch.

"I think that businesses are really frustrated because they're not getting any support from the city," said Joanne Kaufman, executive director of the Warehouse District Business Association.

But it is also a healthy sign for the city's economy. Minneapolis has added more jobs than residents since the tail end of the recession in 2010, a 14 percent rise. And bars, restaurants and taprooms are booming, with a 30 percent rise in liquor licenses over the same period.

At City Hall, growth affects the city's finances. New population has expanded the property tax base, and downtown activity has boosted sales tax and parking revenue. Yet Mark Ruff, the city's chief financial officer, said it comes with an added demand for services — from firefighters handling medical calls to inspectors reviewing buildings and restaurants.

"I think we as a city benefit from nice, measured growth," Ruff said.

'An exclamation point'

Minneapolis city officials have been planning the riverfront boom since the 1970s — and spending millions to get the area ready for development. Around the Mill District, public money built streets in place of railroad tracks, cleaned polluted sites, and invested in preservation projects, including the Stone Arch Bridge, the Depot and Mill Ruins Park.

"Previous City Councils and mayors felt that the riverfront was an opportunity rather than a liability," said Council Member Lisa Goodman, who joined the council in 1998 when there were just a handful of housing developments along the river. "And that reconnecting to the river was the future of cities."

People took notice — and development began to take off — when the Guthrie Theater moved to the riverfront in 2006.

"A lot of people thought it was the Guthrie alone," said Ann Calvert, the city's point person on riverfront issues. "But it was really the Guthrie as an exclamation point to a lot of the earlier development."

Baby boomers and empty nesters looking to downsize were among the first residents to embrace the new wave of downtown living, helping fill the new buildings springing up along the river.

Sue Rogers of Golden Valley was considering the riverfront lifestyle one recent afternoon at a promotional event for Abiitan, a new "active retirement" community in the Mill District.

"You have the house, and the yard, and all that stuff. And suddenly you realize, that's a lot of work," said Rogers, who nonetheless worries about the lack of diversity with higher prices downtown.

The monthly "service fee" for a typical two-bedroom flat at Abiitan, including meals and other amenities, is more than $3,300, after a refundable entrance deposit of at least $170,000.

But Steve Patnode and his wife are glad they left their Eagan house several years ago for a riverfront condo at the Bridgewater near Gold Medal Park. As they walk to the Guthrie and happy hour, they bump into people they know, he said, which gives the city a neighborhood vibe.

"When you're retired, you don't want to wake up in the morning and have nothing to do," Patnode said. "There's activities going on all the time."

Eric Roper • 612-673-1732

Twitter: @StribRoper

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?