Minneapolis Public Schools teachers and educational support professionals went on strike Tuesday for the first time in more than 50 years, prompting the district to cancel classes indefinitely.

Families of the district's 28,700 students scrambled for fallback options, a familiar quandary for Minneapolis parents who have endured two years of pandemic upheaval to their children's education.

Union leaders announced the walkout Monday evening, saying they had been unable to reach an agreement with Minneapolis Public Schools. St. Paul Public Schools was in session Tuesday after the district reached a tentative agreement with the St. Paul Federation of Educators late Monday.

"We're on strike for safe and stable schools and systemic change," Greta Callahan, president of the teacher chapter of the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers, said at a Tuesday morning news conference at Justice Page Middle School in south Minneapolis.

She and other local and national teachers union leaders spoke as dozens of educators chanted and carried picket signs nearby. Callahan said little progress has been made toward settling the union's top issues.

"We're ready to get back to the table," Callahan said. "We want this to be the shortest strike possible."

Negotiations between the union and the school district dragged on for months and the union filed its intent to strike in late February.

The union wants Minneapolis Public Schools to raise the starting salary for educational support professionals from about $24,000 to $35,000. More than 1,500 educational support professionals work for the district, according to the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers. They help with transportation, language translation, one-on-one assistance for kids with special needs, and before- and after-school programs, among other things.

Union leaders are also seeking class-size caps, increased mental health support and "competitive salaries" for teachers, noting that their compensation lags many districts in the Twin Cities metro area. The average salary for Minneapolis Public Schools teachers is about $71,500, according to state data.

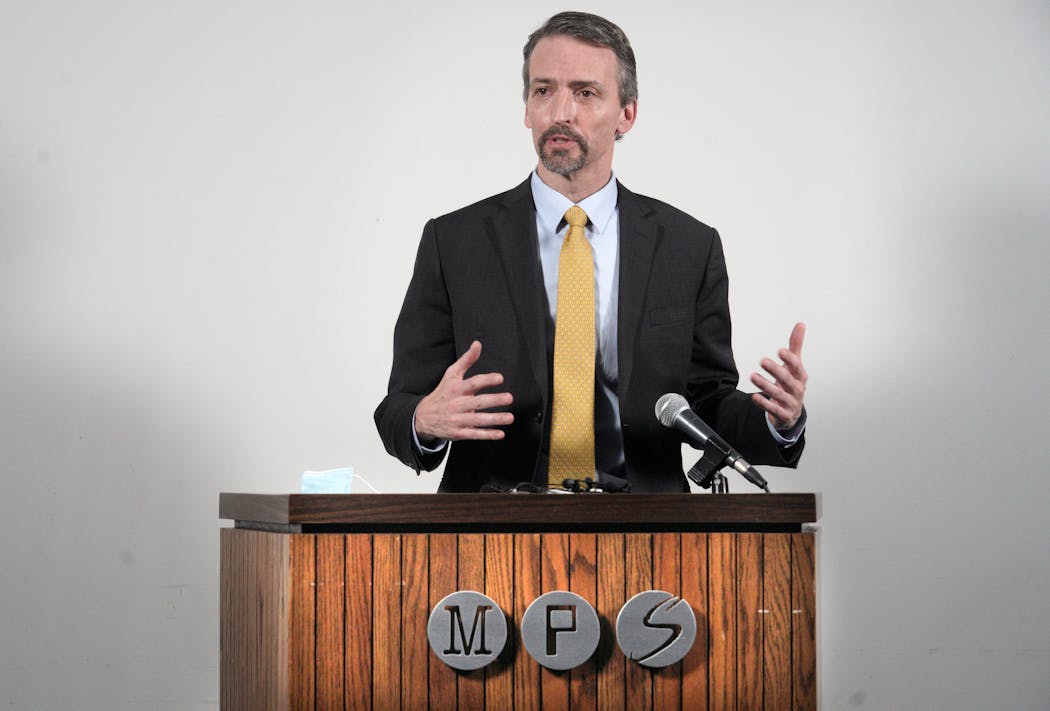

At a news conference Tuesday afternoon, Minneapolis Superintendent Ed Graff said proposals from the union and district are "still very far apart." The total cost of the union's current proposals is "an additional $166 million annually above what we've already budgeted for," he said.

The union was seeking a 20% salary increase for teachers in the first year of the contract and a 5% raise in the second year, Graff said. Union leaders have since lowered their ask to a 12% raise in the first year and 5% in the second year. They have not budged on their request of a $35,000 starting salary for educational support professionals, he said.

"We will need to get very, very creative and figure out how we can close the gap on some of those requests," Graff said. "But we are committed to working with both of our unions. … We know we need to pay our ESPs more. That is something we are committed to doing."

Thousands of educators, families and community members rallied near the district's nutrition center Tuesday afternoon before marching to district headquarters in north Minneapolis.

Chase Hermes Bakken, a special-education assistant at River Bend Education Center in Minneapolis, said he and his fellow educational support staff are the "glue that holds the schools together."

"But we're seen as the bottom of the bucket to the district. So we need this," Hermes Bakken said.

Shannyn Fagerstrom, a social worker working in early childhood at several school sites, joined teachers in a picket line along 34th Street and S. Chicago Avenue. She said she is worried about the district possibly cutting its number of social workers, who are desperately needed.

Fifth-graders have come back to school amid the pandemic with the social skills of third-graders, she said, and some struggle with conflict management.

Natalie Ward, a teacher at Sheridan Dual Language Elementary, said she and her colleagues wished they "didn't have to do it this way."

"It's hard to be out here knowing our kids aren't getting what they need right now," Ward said, "but we're fighting for a contract that will help get them what they deserve."

Minneapolis school board Chairwoman Kim Ellison said the union "has made no movement toward realistic salary proposals."

"All of our teachers are undeniably the heartbeat of our community and they deserve as much as they are asking for," Ellison said. "We just don't have that money."

The school board is committed to raising wages for educational support professionals and the lowest-paid teachers, Ellison said, though she did not specify by how much.

Debbie Lund was watching 22 Minneapolis students Tuesday at Baby's Space, an after-school enrichment program at Little Earth Neighborhood Early Learning Center in south Minneapolis.

The teacher strike is "disruptive, not only for the parents, but for the children," Lund said. "It's another challenge for our families, who are already managing quite a bit."

Mount Olivet Lutheran Church in south Minneapolis took 100 students, from kindergarten through sixth grade, into its child-care program. The church normally runs a preschool-only day-care program with 40 children, said Katy Michaletz, director of children and family ministry.

"We came together as a staff and decided what we could do," she said. The church is committed to providing care this week and will assess the situation Friday. Michaletz hopes the strike will be settled by then.

"That would be the best outcome, right?" she said.

Nokomis Library was packed Tuesday morning with groups of children, accompanied by adults, picking out books for recreational reading, said youth services librarian Lisa Stuart.

Nicole Swickard, whose son is in fourth grade at Webster Elementary, said she understands the teachers union's requests but worries how long the strike may last.

Swickard is looking for ways to keep her son, who receives special-education support at school, busy and learning at home. She watched him scooter around the neighborhood Tuesday and predicted he will want to watch cartoons and movies.

"As parents, we've been through so much these last two years, so it is frustrating," Swickard said. "At least with distance learning, there were online classes. This is harder, and I was just hoping we wouldn't be here."

Dozens of educators from Bethune Arts Elementary bundled up and walked along Hwy. 55 on Tuesday morning. Union members danced to music blaring from a speaker and enjoyed donated doughnuts and coffee.

"This is about our kids," said Randolph Cooper, a substitute at Bethune. "We make the sacrifice for our kids."

Staff writers Erin Adler and John Reinan contributed to this report.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?