Near the end of her battle with COVID-19, Gloria Hays was hanging on, even though the infection combined with asthma made the 89-year-old woman unresponsive and unable to speak.

Her youngest daughter wasn't allowed to visit Hays in her isolation at a Plymouth memory care center but had a worker bring a phone to her mother's ear: "We love you. So many are there with you," Ava McKnight recalled telling her mom. "If you're waiting for us to visit, we can't. Let go in your own time."

Hays died the next morning, on March 26, and was found by another daughter who arrived to see her through an outside window. She was one of the first confirmed casualties of the COVID-19 pandemic in Minnesota.

Death certificate records obtained by the Star Tribune show more of the personal tragedies behind the COVID-19 pandemic — the things that the state's first victims had in common, and the things that made them unique.

Most of those who died were living out their retirement years. Nearly 90% of the 79 reported deaths have been among those over age 70.

They had worked in schools, banking and insurance, health care, farming, homemaking, sales and engineering, according to 63 confirmed or suspected death records reviewed by the Star Tribune. One was a career Navy man, among 27 who served in the armed forces.

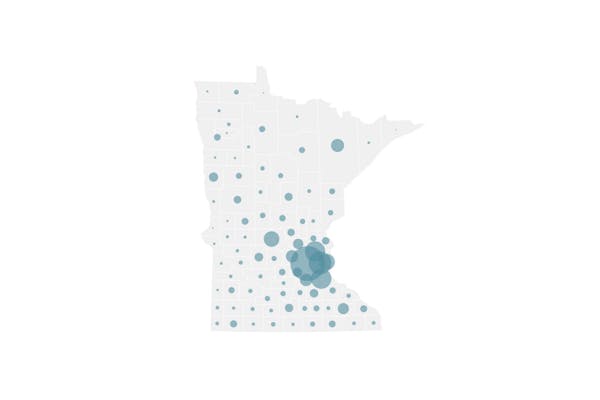

They lived in 32 cities and towns. They were neighbors to residents in Breckenridge near the North Dakota border, Fairmont in southern Minnesota, Duluth, and many of the larger metro-area cities.

Chronic diseases often develop with age, and many had conditions that made them more vulnerable to the new coronavirus. Even among the nine people below age 70 who died, several had underlying health conditions.

Ihor Uniyat was 58 and recovering from a stroke and heart problems in a skilled nursing home in Minneapolis when his breathing became labored and his fever spiked.

His wife was told to go to North Memorial Health Hospital before she realized her husband was at Hennepin County Medical Center. Within only a couple of hours of receiving the news, Svitlana Uniyat found herself in protective garb in the hospital, spending the final minutes with her husband, an engineer from Ukraine who helped her build a home day care.

"How, why, what is happening?" she remembered stammering to the doctor. "I was not prepared."

She didn't know for sure that COVID-19 was a factor until receiving the death certificate nearly two weeks later.

Heart disease and hypertension were common illnesses among those who died of COVID-19, along with diabetes and kidney disease.

Those medical conditions could become part of a revised state COVID-19 response strategy after the current stay-at-home order expires May 4. People with those conditions, or who are older than 60, could be asked to extend their isolations at home into the summer because of their increased vulnerability.

At least 17 of the deceased had two or more of the most common conditions, while others had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease — which makes it hard to breathe — asthma, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis and obesity.

Of all deaths reviewed so far, 98.5% had pre-existing conditions, said Kris Ehresmann, infectious disease director at the Minnesota Department of Health.

Dementia afflicted 15 who passed away, reflecting the fact that about 70% of all deaths have been among residents of long-term care facilities. At least 18 elder-care institutions had lost one or more residents to COVID-19 as of April 10, the most recent death record reviewed by the Star Tribune.

McKnight had looked after her mother until October, when she was moved to a memory care facility because of her advancing Alzheimer's disease. Hays was still smiley and cheerful, singing hymns and even giving advice that an orderly later called life-changing.

Staff at first thought she only had pneumonia and allowed McKnight to stay overnight with her on March 19. Both were diagnosed with COVID-19 shortly after that, requiring McKnight to isolate herself and stay away from work.

McKnight acknowledged a certain sense of peace in knowing that her mother lived a full life and raised four daughters to stick up for themselves. But not being able to see her mom, a classic people person, made it tough.

"It was just excruciating to have her die like that," she said.

For some of those in long-term care, they died where they lived. Although some were sent to a hospital, 27 passed away at the elder care facility.

Of all deaths, 35 were at hospitals and one was at a private residence.

As of now, deaths have not been concentrated at any one hospital, with the largest number — three — occurring at each of six hospitals: the Minneapolis VA Medical Center, HealthPartners' Regions and Methodist hospitals, Mayo Clinic's hospital in Mankato, and M Health Fairview's Southdale and Bethesda Rehabilitation hospitals. Bethesda was recently turned into the state's first hospital dedicated to COVID-19 patient care.

Public health officials typically do not disclose names of people affected by an outbreak, whether it be COVID-19, seasonal flu or food poisoning. But in Minnesota, death records are public information, including names, addresses and cause of death information.

State epidemiologists are analyzing all COVID-19 deaths to see what they can learn about who is at greatest risk and what treatment options are effective. The high rate of deaths involving long-term care has prompted intense testing and observation of residents, Ehresmann said.

"That is where we are putting our energies in terms of trying to be proactive in reaching out to those facilities, offering assistance and providing training and guidance," she said.

In a review of medical records from 146 hospitalized patients, the state found 25 people whose infections caused such profound breathing problems that they were intubated and placed on ventilators. Of those, nine died, six survived, and 10 are still receiving intensive care.

Most deaths from natural causes do not involve an autopsy — those are usually reserved for accidents, suicides, homicides and deaths from unexpected causes.

Instead, state and national officials rely on the judgments of doctors and other clinicians, who are the only ones who can determine cause of death, to provide an explanation of how a death occurred.

The state receives death information from funeral homes and health care workers electronically and has been closely monitoring incoming records for reported COVID-19 cases to track the outbreak.

Of the 63 records reviewed by the Star Tribune, 10 indicated that COVID-19 was either suspected or that test results were still pending. Those cases are not included in the state's official count of deaths.

State officials are working with doctors and others to get each case confirmed, said Molly Crawford, who oversees death records at the Health Department.

Although the death records show the toll that COVID-19 has taken on the elderly, it is a disease that affects all age groups. More than 70% of the 1,695 confirmed cases have sickened people younger than 65. A 4-week-old baby was among the 405 people who needed hospital care and the youngest ICU patient was 25, according to the Health Department.

Gov. Tim Walz on Tuesday reminded people of the need to maintain social distancing to protect people who are most vulnerable. The current stay-at-home order is designed to reduce face-to-face contact and virus transmission by 80%.

"Minnesotans are still continuing to keep our (COVID-19 case) rate the lowest in the country," Walz said. They're "maybe very frustrated, maybe very just tired of this in social distancing, but they're doing it."

---

If you have lost a family member or friend to COVID-19 and want to share their story, please e-mail the Star Tribune at coronavirus@startribune.com. We will not publish details of your submission without your permission.

Data editor MaryJo Webster and staff writer Matt DeLong contributed to this report.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?