The Walz administration is making a push with millions of dollars in grants to help adults with disabilities move into the mainstream workforce and out of jobs that pay less than the minimum wage.

For decades, Minnesotans with disabilities, including Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and autism spectrum disorder, have toiled at menial jobs that pay less than the federal minimum wage — a practice that has long been decried by civil rights advocates as discriminatory and archaic. Under a loophole in federal law, employers that hold special certificates can pay people with disabilities based on their productivity, rather than a fixed hourly rate. Pay through this system, known as "piecework," often amounts to just pennies on the dollar.

From 4,500 to 6,000 Minnesotans with disabilities made less than the minimum wage in 2021, according to a state task force report. Many work at day and employment centers — sometimes referred to as "sheltered workshops" — that receive state funding to provide a broad range of support services.

Prodded by years of activism and a new state law, the Department of Human Services (DHS) and disability service providers have been exploring alternatives to this unequal payment system. On Friday, the department announced that nearly two dozen employment service providers across the state will receive a total of $10.5 million toward supporting adults with disabilities work in mainstream jobs at competitive wages.

The grants, funded by the federal American Rescue Plan Act, will help eight day employment centers phase out subminimum wage work by April 2024 — and another 14 providers expand employment supports. The money will also go toward job coaching, career exploration and other services that will help individuals with disabilities find and retain jobs in the general workforce.

"Working-age Minnesotans with disabilities deserve to be offered opportunities to work and earn competitive wages," Natasha Merz, interim assistant commissioner for the aging and disability services division at DHS, said in an interview Friday.

"Investments like this help move our system towards community inclusion, equitable wages, and address some of the workforce shortage challenges that we're seeing across all of our industries."

The practice of paying subminimum wages began during the Great Depression as a way to give people with disabilities a chance to learn job skills. But in recent years, it has come to be seen as antiquated and a violation of civil rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

A Star Tribune investigation in 2015 found that many of those in Minnesota's workshops spend years toiling in poverty and isolation with little hope for advancement. Some 13 states, including Alaska, Colorado, Maryland, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island and Vermont, have enacted laws to prohibit subminimum wage employment in the hope of integrating more people with disabilities into the general workforce.

Some disability rights advocates argue that workers should not be paid less than the minimum wage — just $7.25 at the federal level — under any circumstances because it's discriminatory and can lead to exploitation. Others say the practice is still needed to give employers an incentive to hire people who may be less productive — and can create work and social opportunities for people who might otherwise not have them.

In a 2020 report, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, an independent federal agency, called for the repeal of the section of federal law that enables employers to pay subminimum wages. The report concluded that the practice is discriminatory and prevents people with disabilities from "realizing their full potential."

Julie Johnson, president of MSS, a St. Paul-based disability service provider that received $350,000 through the new grants, described the infusion of new money as a "really, really big deal."

Her organization has long provided on-site job coaching and other employment services for people at its six Twin Cities locations. The grant will help MSS hire staff to expand those services to a wider pool of people while adding programs.

With the new funding, for instance, the organization can hire a staff person dedicated to helping people with disabilities become self-employed or create their own businesses. The nonprofit also will step up efforts to help people find careers they are interested in through job shadowing and tours of worksites.

MSS said it expects the grant money will help at least 50 clients move to competitive employment through the end of 2023 — on top of the roughly 100 clients it helps find mainstream jobs each year.

"Some of this is really about trying to figure out what people are interested in," said Michelle Dickerson, vice president of program services at MSS. "You know, we are all happier if we have jobs that we're interested in."

Last year, the Legislature recognized the growing movement nationwide against subminimum wage employment and authorized the creation of a state task force to develop a plan and make recommendations to phase out the practice before Aug. 1, 2025.

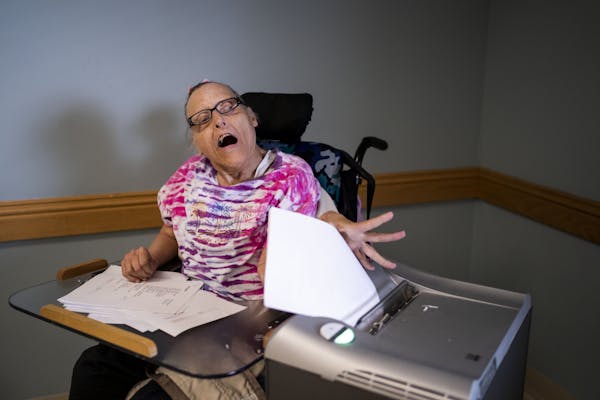

Krystal Halford, 32, who has Asperger's syndrome and autism, said the move to phase out subminimum wage work is long overdue.

For most of her 20s, Halford worked for as little as $2 an hour doing assembly work at warehouse-like employment centers in the Twin Cities. She was paid based on the number of boxes and other items she assembled, which meant her pay would decline when the assembly line slowed down or malfunctioned. Because of her developmental disability, she had difficulty expressing to people at work that she wanted to move on and try more fulfilling work.

Eventually, with the help of a job coach, she found a job at a laundry service for $16.50 an hour.

"It's been a huge psychological boost to finally make a competitive wage," Halford said. "I no longer feel defined by my disabi

lity."

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?