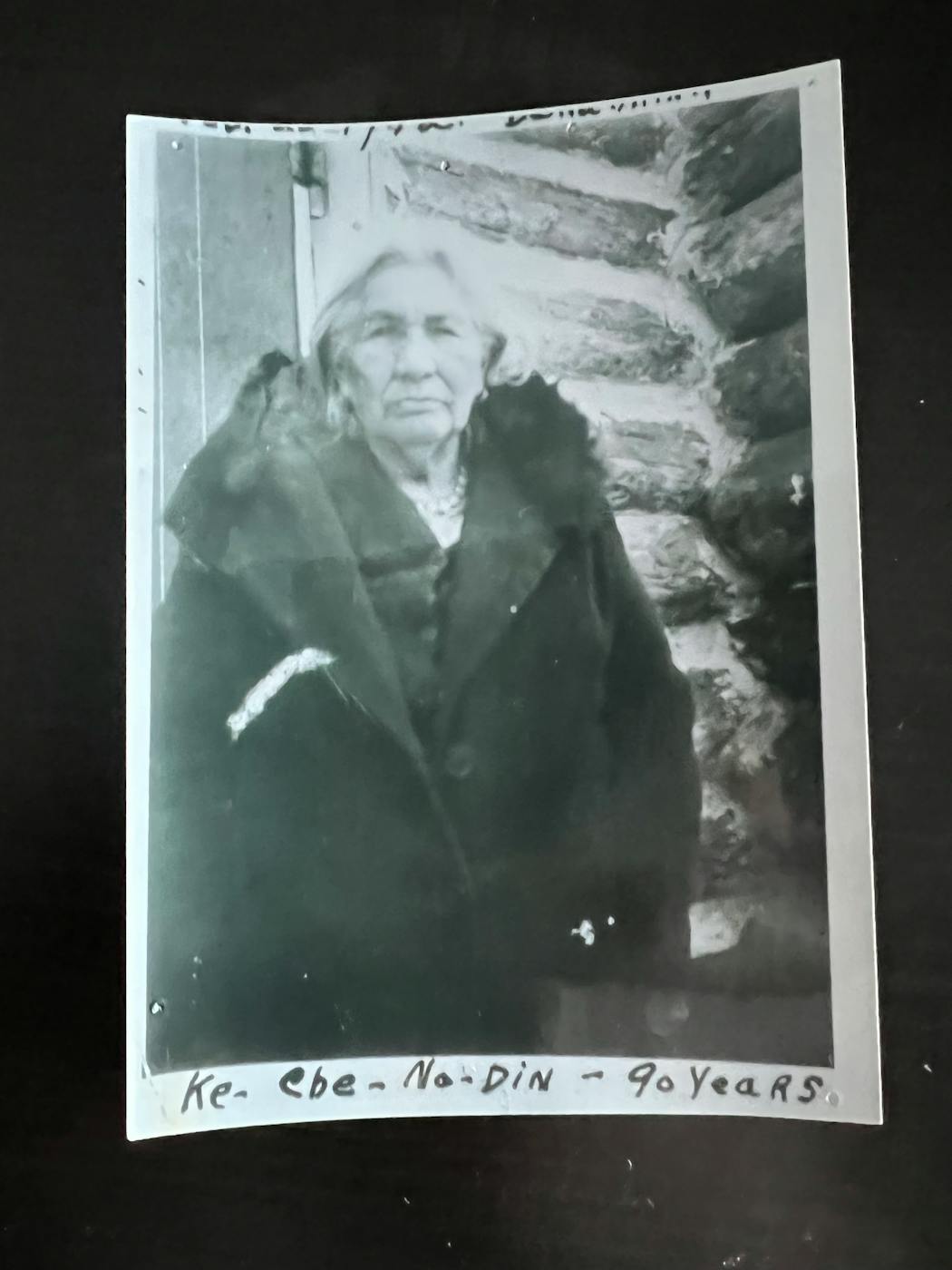

Tony Drews was excited when, in elementary school, he received his Ojibwe name, Chinoodin. His grandmother's cousin gave it to him, explaining that it was the name of Drews' great-great-grandmother and that he should honor it.

"It was a great time — I felt so Ojibwe!" said Drews, a member of the Leech Lake Band.

But his father, wanting to protect him, instructed him not to talk about it at school. As a kid, his father had been ridiculed and beaten for being Native American.

He tells the anecdote to help explain how the Ojibwe culture and language faded. Drews, who studied Ojibwe as a student in American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota, wants to reinvigorate the language and culture of his ancestors.

He spent five years working in Anoka-Hennepin schools as an Indian education adviser. When he would make references to Ojibwe culture, Native students would respond with blank stares.

"It became apparent to me that the students I was working with knew very little about their culture," he said.

That's why Drews developed Nashke Native Games, a collection of parlor games. (The word "parlor" may summon images of an old-fashioned sitting room, but it comes from the Latin word "parlare," meaning to speak.) The games, being used in 15 school districts, are designed to teach awareness of Ojibwe language, cultural practices, history and traditional imagery.

Nashke games (the name means "look, behold!") include original card games and puzzles, including some for young children, that introduce Ojibwe words. The Bineshiiyag (the Ojibwe word for birds) games focus on various species of birds (owl, hawk, blue jay). Mii Gwech (meaning thank you) games teach the significance of objects from the fur trade era (beaver hide, canoe, moccasins, blankets).

Others are inspired by traditional Anishinaabe games: Bagese (meaning, "to throw") is like a dice game, Makizinataagewin, the Moccasin Game, is a complex board game, Ginebig, the Snake Game, features four sticks shaped like snakes.

Drews recently launched a 28-day fundraising campaign for production of his newest game, Giiwen. In Nashke's first contemporary board game, players follow the seasonal activities of the Anishinaabe, experiencing traditional Indigenous ways and customs. Giiwen players are exposed to words for numbers, family members, geographical landmarks and tools.

Drews received multiple grants to support the project, including a $50,000 fellowship stipend from Finnovation Lab, which invests in start-ups with products that make a positive impact on health, sustainability and equality.

Half of whatever profits the games generate will be donated to Native community events and partnerships, Drews said.

"I was so excited when I found out Tony was doing this — somebody who wants to create games for their community," said Rebecca Goff, co-founder and executive director of Montana-based Native Teaching Aids, which develops resources that teach indigenous languages, cultures and history. The company manufactures and distributes Nashke Native Games. "We would love to see more people like Tony coming out of the woodwork."

Some kids' interest in cultural education can be sparked by typical classroom methods (reading, writing, memorizing, tests). But many respond more enthusiastically to games, said James Vukelich, a longtime friend of Drews'.

"We see a need in the community for language games, for getting people involved in the language through a different medium rather than just coursework in classes," said Vukelich, who is the author of "The Seven Generations and the Seven Grandfather Teachings" and has a YouTube channel about Ojibwe words.

Learning a language requires practice speaking it, but opportunities for Ojibwe conversation are few, Drews said. The games provide a setting where people can try out words without being self-conscious.

"With these games, you can just sit down and play," he said.

A cultural hero

Drews' great-grandmother spoke only Ojibwe. But as a child, his grandmother, like many Indigenous children of her era, was taken from her family's home and sent to a boarding school. At Pipestone Indian Boarding School, students were forbidden to speak Ojibwe or to practice their culture or religion.

"They were told, 'Everything you know is wrong,'" he said. "You'd get beaten if you spoke your language. They'd be told, 'The god you believe in is not the right god.' ... I can't imagine the trauma her generation went through."

The boarding schools nearly eliminated knowledge of Ojibwe language and cultural heritage. His father doesn't speak it. Fewer than 1,000 people speak Ojibwe.

"It only took one generation to erode completely my family's language and a millennium of our cultural knowledge," Drews said.

That pattern was replicated across the continent. There are 256 Indigenous languages spoken in North America — far fewer than the original number, and 238 are threatened, Goff said. Although efforts are underway to revitalize those languages, the people who speak them are aging out.

The situation is improving — in a 2021 survey by the Prior Lake-based Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community, 90% of Minnesotans expressed support for "increasing the teaching of Minnesota's Native American history, culture and tribal government in the state's K through 12 public schools."

But there's a long way to go. As an example of what's being lost, Drews pointed to a figure on one of his game cards.

"This guy here, he's our cultural hero, Nanaboozhoo," he said. Nanaboozhoo represents Ojibwe ancestors, but few young people can identify him. "It's the equivalent of being Christian and not knowing who Jesus is."

But Drews, who describes himself as a "glass half-full kind of guy," is determined to do what he can to preserve his language and the culture it represents.

"As long as there's one word left, our language will never die," he said.

Critics' picks: The 11 best things to hear, do and see in the Twin Cities this week

Critics' picks: The 9 best things to do and see in the Twin Cities this week

The 5 best things our food writers ate this week

The 5 best things our food writers ate this week