As a part-time nurse at the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Megan Murphy has twice been forced to take a leave from work this summer while waiting to get tested for COVID-19.

On both occasions, Murphy had good reason to believe she'd been exposed to the virus and stayed home, as required by hospital policies, to limit spread of the disease. Each time, it took four to five days to line up an appointment and get the results.

Both tests came back negative. But a snafu delayed the results of Murphy's first test and left her without enough paid time off to cover her second leave. As a result, she lost two days' pay and has no sick time left.

"I'm still going to be honest" in disclosing future exposures, she said. "But my concern is, what happens when people can't afford to have two days unpaid, and they no longer acknowledge that they have symptoms or have been exposed because they can't afford to miss work?"

Murphy's predicament is one many health care workers face as COVID continues to spread. While policies vary depending on the hospital, some workers say it's becoming increasingly difficult to get paid for time off if they feel potential symptoms or have risky exposures.

At Allina Health facilities, workers get can get 14 days of paid leave for COVID-19 — if they test positive. M Health Fairview employees can get paid for all shifts missed — if the exposure happened at work.

"We pay employees for all time missed due to a workplace exposure," M Health Fairview spokeswoman Aimee Jordan said. "We trust that employees who feel symptomatic will not come to work because of their commitment to patients and the care they provide."

The issue inspired worker demonstrations at two hospitals last week by SEIU Healthcare Minnesota and is driving the Minnesota Nurses Association to support state legislation to address it.

State House Majority Leader Ryan Winkler said a bill slated to be introduced in the House and Senate on Monday would require hospitals and nursing homes to give paid time off to health care workers who need to go on leave for COVID testing and quarantine.

It would complement a law passed in April that stipulated COVID-19 infections among health care workers are presumed to be occupation-related for the purposes of workers' compensation.

"People who are working to protect us and provide health care have no choice but to be exposed. [They] shouldn't also have the financial exposure of missing work," Winkler said. "They need their income just like everybody else does."

State data show that health care workers — those in hospitals, nursing homes, clinics and elsewhere — comprise more than 10% of all the state's lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19. State data say 80% of health care worker exposures tracked by the state are classified as occupation-related.

There is evidence that occupational exposures are less risky than other kinds. Minnesota contact tracing shows that as of August, less than 2% of health care workers' high-risk exposures to COVID-19 patients resulted in a positive diagnosis in 14 days, vs. nearly 11% for household or social exposures.

"Health care systems are finding very few infections that can be traced back to exposures at work since we started using universal masking procedures," said Dr. John Hick, an emergency medicine doctor with Hennepin Healthcare who serves as a medical adviser to state health and security officials.

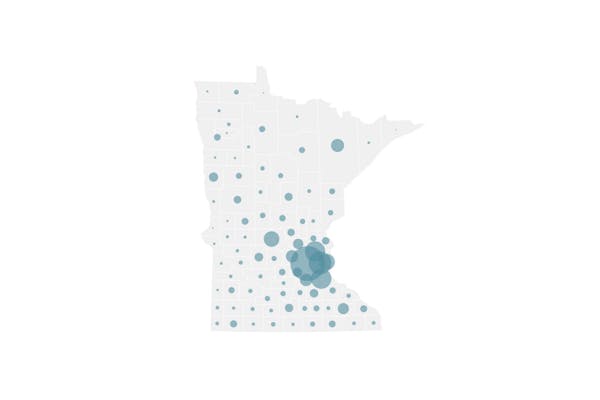

Overall, Minnesota has recorded 112,268 lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19 since March 5, including 1,450 cases added to the tally Sunday by the state Department of Health. The state hit an all-time high of newly reported cases the day before, with 1,516.

Minnesota has recorded 2,141 deaths from the respiratory illness, including 10 announced Sunday. The new deaths included two people between 45 and 54 years old, and eight ages 65 or older. Three lived in long-term care; seven lived in private homes.

Private labs have been processing between 12,000 and 32,000 tests per day for Minnesotans using the gold-standard diagnostic technology, which is a PCR test that detects molecular traces of viral genetic material. (PCR stands for polymerase chain reaction.)

But some workers on the front lines of health care say it still takes them a day or more just to get an appointment for a test, and two to three days to get the results. Those delays can lead to unpaid time off, depending on whether the exposure happened at work and whether the test comes back positive.

Minnesota Hospital Association spokeswoman Wendy Burt said hospitals do prioritize testing for employees, but the timeliness is affected by whether the hospitals are processing the tests in-house or at external labs.

An adequate supply of rapid COVID tests that produce results in less than a day would essentially eliminate testing-related delays for health care workers. Abbott Laboratories sells a rapid molecular test called the ID NOW, and five companies now offer fast-acting antigen tests.

But ID NOW tests are in limited supply, and public health officials have concerns about whether antigen tests are as accurate in the field as the manufacturers' validation studies claim. The Health Department recommends using a second test to confirm antigen test results in many circumstances.

Spokespeople for Allina and Fairview said their rapid COVID tests are reserved for hospital patients.

"We continue to invest in equipment that will increase our testing capabilities and will continue to make adjustments in our protocol as our testing capacity changes," Allina said in a statement.

Joe Carlson • 612-673-4779

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?