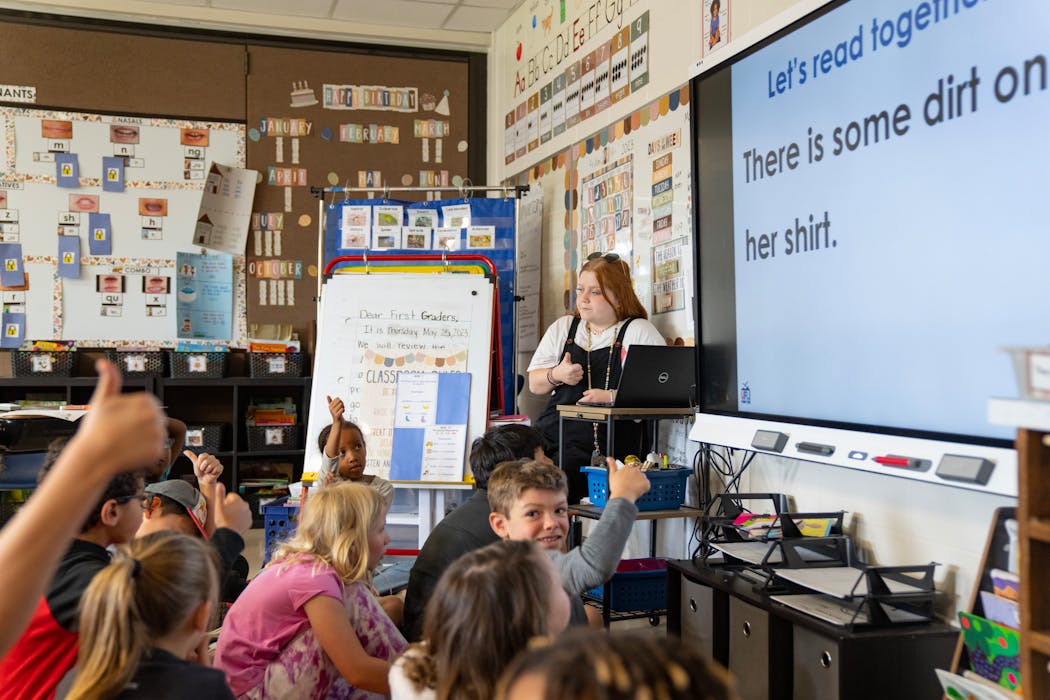

The bulletin board in Krista Sorgatz's first-grade classroom at Wilshire Park Elementary is adorned with an array of paired letters, each representing a different sound. Illustrations of padlocks also decorate the wall, signifying lessons the kids still need to "unlock" — as soon as they master the prerequisites.

This orderly approach to reading lessons is uniform across every classroom in the St. Anthony school and will soon be standard across the St. Anthony-New Brighton district.

"When I got here, we didn't have alignment around reading," first-year Principal Maria Roberts said. "And I told my superintendent that I needed a literacy coach, an instructor for my teachers."

The school's efforts are exactly what Minnesota legislators are hoping to replicate across the state under the sweeping education bill Gov. Tim Walz signed into law. The literacy-education elements of that measure drew bipartisan support and ushered Minnesota into a growing movement nationwide that overhauls efforts to teach kids to read.

It requires schools to adopt a type of instruction known as the "science of reading" to qualify for state funding. The research-backed method is often understood as a return to an emphasis on phonics and phonemic awareness — how words are made up of a series of sounds — for all students, not just struggling readers.

"What you're going to hear is that we're going back to the basics somewhat in how students are learning," said Bobbie Burnham, assistant commissioner for the Office of Teaching and Learning at the Minnesota Department of Education.

The plan will require Minnesota school districts to choose from a list of at least five Department of Education-approved literacy programs and provides funding for educator training and classroom materials.

It also requires schools to screen every student at the beginning and end of their first four years in school, a practice that has been reserved for children identified as struggling readers. And it encourages schools to develop a variety of plans to support students, regardless of their reading ability.

Most important, lawmakers and educators say, the bill standardizes the approach Minnesota's teachers take in tackling one of the thorniest and persistent issues in American education.

'Unacceptable' reading scores

About half of U.S. fourth-graders scored below proficient on a widely administered national reading assessment last year. In Minnesota, nearly half of public school students also missed their reading benchmarks last year, according to state testing data.

That worries Kim Gibbons, director of the Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement at the University of Minnesota. The center is tasked with identifying which classroom materials and trainings will qualify for state funding by the end of the year.

"We've got almost 500,000 kids that aren't proficient, and that would fill up the U.S. Bank Stadium 7 ½ times," Gibbons said. "That's unacceptable."

Until now, Minnesota districts were largely left to adopt whatever trainings and classroom materials they wanted — some of which have since fallen out of favor. But shifting to the "science of reading" could be costly, with some programs coming with a price tag of up to $1,000 per teacher license.

Gibbons, who spent two decades working for the St. Croix River Education District, said Minnesota's literacy legislation follows what several states have already done. Places like Mississippi and Alabama have made headlines for the gains children have made in reading proficiency using similar tactics.

In the last decade, 31 states and Washington, D.C. have passed legislation or adopted policies to revamp the way young children learn how to read, according to a tally by news organization EducationWeek.

Minnesota was one of three states considering bills to centralize reading supports at the state level this year. Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine has pushed a $64 million investment in the "science of reading." In Oregon, a push to fund a similar effort remains in limbo.

But while lawmakers in some states have focused on prescribing specific programs, Gibbons advised politicians in St. Paul to ensure funding for professional development and support specialists to help Minnesota teachers.

That's why the bill provides $35 million for teacher training, in addition to $35 million to reimburse districts for new classroom materials if they need to replace recently purchased books and lesson plans that don't align with the new state standards.

"The research is pretty clear that you need all of these elements working together," Gibbons said.

Bipartisan support

Minnesota's new literacy efforts stand out from those of other states in the emphasis on data collection, said Rep. Heather Edelson, DFL-Edina, who authored the literacy portion of the education bill. Districts will be required to report the curriculum they use to the state, which Edelson said will offer insights on which classroom materials are most effective.

"We will have comprehensive data on what's happening throughout our state — who's using which curriculum, which interventions they're using. And maybe we can identify some trends," Edelson said.

All but one Republican voted against the larger education bill, but the literacy provisions received bipartisan support throughout the Legislative session.

Sen. Zach Duckworth, R-Lakeville, said he is often against mandates for schools because they leave little room to provide support for individual students who may be struggling.

"If we are pulling you and your staff in so many directions, something's got to give," said Duckworth, who voted against the larger education bill.

But as literacy rates in Minnesota and across the country have steadily declined over the years, Duckworth has heard a consensus — from school boards to the governor's office — that educators needed help. And he supports the new literacy efforts.

"When we see those rates begin to slip, whether you're a Republican or Democrat, you know there's something we have to do at the state Legislature," he said.

Roberts, the Wilshire Park Elementary principal, said it was reassuring to see that lawmakers provided funding for instructional coaches and also mandated state coordination of districts' efforts.

Gibbons, the university researcher, agreed with the multi-pronged approach, saying policymakers have too often looked to individual teacher training programs or curricula as a silver bullet for anemic gains in literacy.

"There's not one simple fix. It's not a matter of just picking curriculum off a list," Gibbons said.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?