Every so often, Cassie Carter collapses on her teenage son's empty bed after a long day at work and reflects on his childhood — his first day of kindergarten, the long afternoons they spent playing at Como Park Zoo in St. Paul. It is how she reminds herself that, until a couple of years ago, her son Jayden was "just a normal, big-hearted kid" adored by his siblings and cousins.

Those days now seem a distant memory. At age 12, the child who once dreamed of being a police officer fell in with a group of boys who skipped school and brandished handguns on social media. Before long, Jayden was vanishing from home for weeks at a time and roaming the streets of St. Paul — shoplifting from stores, burglarizing homes and fleeing from police in stolen cars.

Each time he was caught, Carter pleaded with law enforcement and county social workers to place her son in a locked juvenile facility with round-the-clock surveillance. Only then, she believed, would he get sustained treatment for his behavioral problems and reflect on the harm he was inflicting on his family and many victims.

But each time, he was returned to the community with little or no support services, only to resume his dangerous crime spree.

"His crimes keep escalating, but the outcome is always the same: Catch and release, catch and release," said Carter, a carpenter and single mother. "The system is teaching my son that he can break the law, over and over again, without any consequences."

JUVENILE INJUSTICE

A series examining how Minnesota's juvenile justice system is failing young people, families and victims of violence.

Part 1: Broken promises, shattered lives

Part 2: Justice 'by ZIP code, not fairness'

Part 3: Nowhere to go for most troubled youth

More than a decade ago, Minnesota lawmakers, prosecutors and judges embarked upon a quiet revolution in the way minors were held accountable for their crimes. Locking kids up, routine for even some petty offenses like truancy and shoplifting in the 1990s, became a last resort in many counties. The emphasis shifted instead to rehabilitation, with teens being steered toward community-based programs such as mental health counseling, mentorship and job skills training.

The reforms spared tens of thousands of children a criminal record, especially Black youth, who were far more likely to be arrested and confined to locked detention centers than their white counterparts. But a Star Tribune examination of hundreds of juvenile-court records finds that the new approach is failing to effectively intervene in the lives of Minnesota's most troubled kids, often despite anguished pleas from parents.

In the last four years, about 30% of youth arrests in Minneapolis and St. Paul were teens who had been arrested at least one time in the previous year by the same law enforcement agency. Records show that, in Minneapolis, 22 children were either arrested or sought in connection with six or more carjackings or robberies since January 2020. Some suspects were as young as 12 or 13.

The revolving door

In two years, 49 youth were suspected or arrested in at least one carjacking offense by Minneapolis police. Many had been suspected or arrested in previous carjackings, which sometimes occur in quick succession.

Even after children are charged and prosecuted in county courts, they continue to reoffend at alarmingly high rates, court records show. In 2020 in Hennepin County, 40% of youth who were , or found guilty by a judge, were charged with new crimes within 12 months. The rate is similarly high for Hennepin County youth who are being supervised in the community by probation officers. In Minneapolis, a startling two-thirds of minors arrested for carjackings between June 2020 and last November had at least one other arrest within the previous year, police records show.

Many of the rehabilitative services promised as an alternative to and other punitive measures have been outsourced to a patchwork of underfunded nonprofits. The burden of making sure children participate in the programs often falls on parents and guardians who are sometimes struggling with their own problems, including housing instability and substance abuse. Tracking of attendance or outcomes is so haphazard that some county officials acknowledge they have no idea if the community-based programs are benefiting youth and their families.

Meanwhile, some of the most essential services, such as chemical dependency treatment and psychotherapy, are made available only after a minor has been formally charged with a crime. That revelation can be a shock to parents desperately trying to change their child's trajectory. "It's very sad to see youth falling through the cracks of the juvenile justice system, but we see it happening all the time," said Beth Holger, chief executive of the Link, a Minneapolis nonprofit that provides housing and other support services for youth.

In her 15 years on the juvenile court bench, Hennepin County District Judge Tanya Bransford said that she has never seen as many exasperated parents — and such a high demand for mental health and other support services. She said the juvenile system lacks adequate residential treatment centers where adolescents who have committed serious offenses can be evaluated by trained professionals and learn how to change their behaviors.

"If you have young people who are shooting other people, then I don't think it's safe to say, 'Fine, now just go back to the community,'" Bransford said. "I don't think the community thinks that's safe either."

For five years, LaTonya Reeves begged for mental health therapy and other support services for her son, who began lashing out — smashing furniture and assaulting his siblings — at age 10.

Soon he was being picked up for trespassing, assault and disorderly conduct. Convinced his behavior was a symptom of mental distress, Reeves sought in-home therapy for her son and an after-school mentorship program. Her pleas for assistance were ignored even as his behavior escalated.

Now 19, her son is sitting in the Hennepin County jail, facing up to 20 years in prison for his alleged role in a gang-related shooting in November 2020 that seriously wounded two people.

"Had my son got the services he needed when I begged and pleaded for them, then he wouldn't be in trouble today," said Reeves, who works as an adult probation officer. "As parents, we feel invisible, that we're out here on our own without any idea of how to get help for our kids."

Victims feel betrayed

The failings of the juvenile justice system are being felt across the Twin Cities. Survivors of violent crimes say they feel betrayed when teens are not accountable for their actions. And parents of those youth feel abandoned by a convoluted system that promises rehabilitation yet allows their children to hurtle down a dangerous, sometimes deadly path.

The consequences of that inaction can be devastating: At least eight youths have died since early 2020 while joy riding in stolen cars. Just before the holidays last year, a group of kids attempting to evade police in a stolen Mercedes-Benz SUV lost control in northeast Minneapolis and crashed, severing the vehicle in half and killing two young passengers on impact. It marked the fourth such fatal pursuit in just two years.

Documents show that each case involved minors who already had lengthy criminal histories.

Some teenagers were caught only after brazenly streaming videos of themselves while driving at high speeds in stolen cars.

"It's an idle-hands thrill ride," said Booker Hodges, Bloomington police chief and former assistant commissioner for the Minnesota Department of Public Safety. "Social media and unsupervised kids is a bad combination."

Alex Swenson is still grappling with the terrifying memory of seeing his children swept away during a violent carjacking outside their St. Paul home two years ago.

Swenson was adjusting his 1-year-old daughter's car seat one afternoon when an approaching teenager battered him to the ground. Several others swarmed and began kicking him. Jodi Swenson-Weisser stepped outside to find her husband lying in the street, curled in a fetal position to protect his body from repeated blows. In shock, she dropped her 8-year-old son's birthday cake as another teen peeled away in the family van carrying two of their children.

"My kids are in there!" Alex Swenson screamed as his son wailed from the back seat.

The teenage driver accelerated through the intersection, stopping suddenly before running away.

Fifteen minutes later, an off-duty police officer caught 10 minors attempting to use Swenson's credit cards to buy gift cards at a nearby Target. Prosecutors pursued aggravated robbery and kidnapping charges against seven boys. One case was dropped, but six pleaded guilty to reduced robbery charges.

The Swensons attended every court hearing they could. Jodi wanted the teenagers to see their faces and understand the suffering they had caused. Alex wanted them to know the terror of watching his children be stolen from him — and how, for weeks after the assault, he and Jodi were forced to repeatedly explain to their 3-year-old that 'no, Daddy isn't going to die.'"

In a victim impact statement, Alex Swenson asked the carjackers to learn from their actions. "I hope they never cause anybody else this kind of emotional or physical pain," he wrote. "I hope they think of somebody else besides themselves."

All the boys were eventually released on and, according to police and court records, most began committing a string of robberies in the months to follow.

One was caught with a group holding up suburban gas stations, including one crime in which a Golden Valley clerk was shot and paralyzed. Authorities tied another boy to the back-to-back carjackings outside Lunds and Byerly's stores in St. Louis Park and Edina last December. Rayevan Smith, now 18, was recently sentenced as an adult to seven years in prison for his role in four armed carjackings.

One of the youngest suspects in Swenson's case, 15-year-old Jamontae Welch, died eight months later when the stolen vehicle he was riding in crashed during a police pursuit.

The tragedy stirred a complicated set of emotions in Alex Swenson. His heart ached for Jamontae's parents, because no one should ever have to bury their child. But how had no one intervened? Why were the teens allowed to continue hurting people?

"The juvenile system literally is just a slap on the wrist," Swenson said. "The whole community is failing them."

A tougher approach

The recent surge in carjackings belies the fact that the arrest rate for teenagers in Minnesota and elsewhere has been steadily dropping over the past five years. But the frequency and ferocity of these crimes is provoking outrage in community forums, at city halls and the State Capitol.

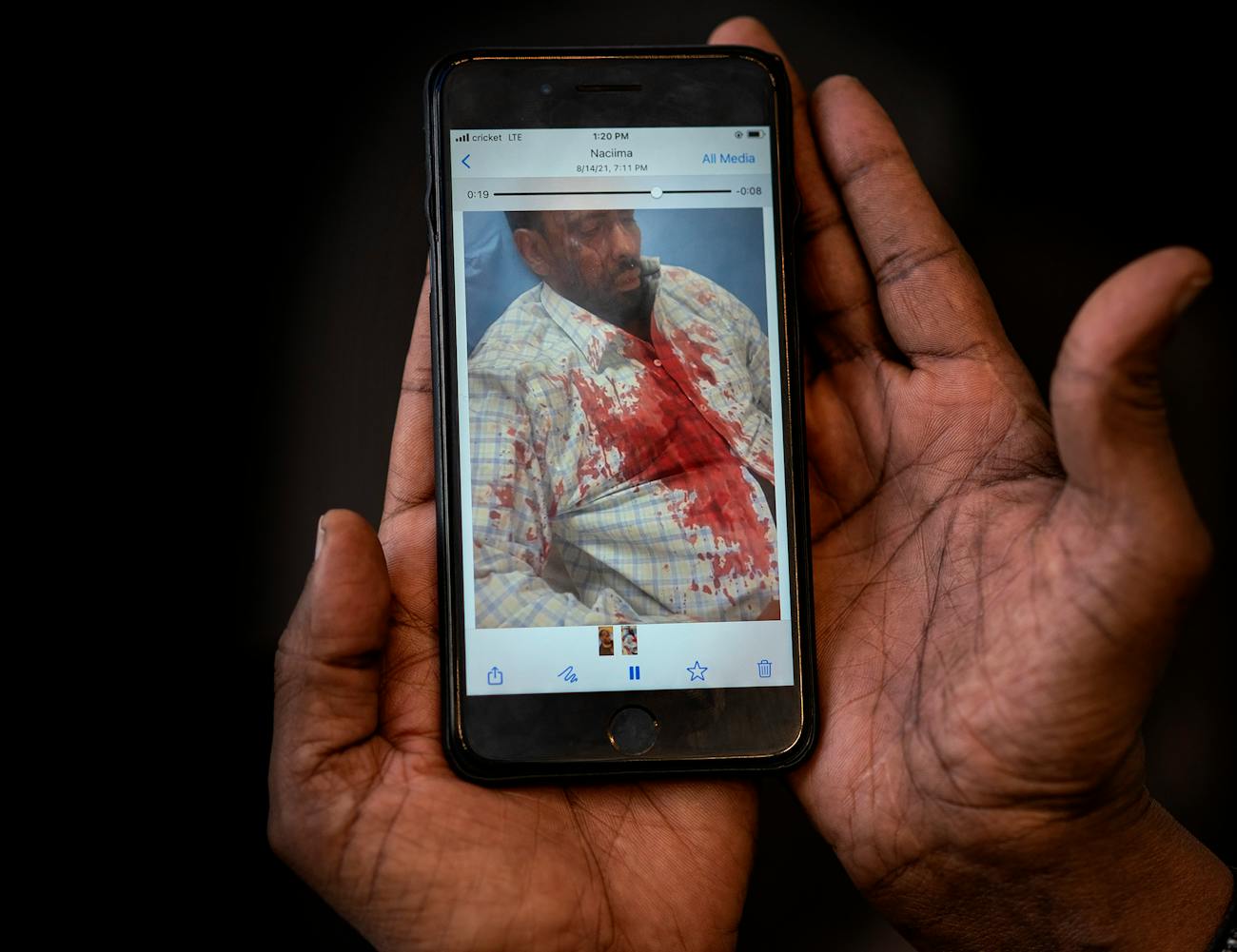

Abdullahi Abdi, an Uber driver who lives in Burnsville, was found covered in blood and barely able to walk after a 16-year-old boy repeatedly struck him with a metal rod while trying to steal his phone. The assault was so severe that, six months later, Abdi was still unable to lift both arms above his head and has had to learn how to read lips because the many blows permanently damaged his hearing. He also learned to scrutinize each of his Uber passengers for hints of trouble, and to cancel rides when he sees people who look like the teenager who left him bleeding along a dark road.

"For 16 years I have lived in this country and had no problem," said Abdi, 62, who fled Somalia's civil war in the 1990s. "Now I think it is unsafe to live here."

Criminal justice reformers and many county officials blame much of the problem on the pandemic that upended children's lives and a dearth of child and family services. DFL Gov. Tim Walz recently recommended allocating more than $20 million over the next four years toward after-school programs, mentoring and other programs for youth, as well as conflict resolution centers that help connect teens with services.

Republican lawmakers and law enforcement officials argue the attacks demand a tougher approach. Former Senate Majority Leader Paul Gazelka, a Republican candidate for governor, has called for mandatory minimum sentences for carjackers and other juvenile offenders he accuses of terrorizing the urban core. "Instead of learning math and science and social studies, they're learning to become hardened criminals," Gazelka said.

The rhetoric echoes that of an earlier era.

In the early 1990s, a surge in homicides and other violent crimes among youth ushered in a wave of intensified policing and tougher sentencing laws that blurred the once-stark distinctions between the juvenile and adult criminal systems. Some criminologists warned of a new breed of violent youth, or "superpredators," who terrorized victims without remorse. Lawmakers in Minnesota and more than 40 states responded by enacting laws that made it easier to prosecute children as adults.

But the projected youth crime wave never materialized. Homicides and other violent crimes by adolescents plunged before tougher sanctions were even imposed.

By the early 2000s, the pendulum began swinging back toward rehabilitation. New research showed that locking up youth often resulted in them dropping out of school and becoming permanently entangled in the criminal justice system. There was also growing outrage over the harsher treatment of kids of color, who were being arrested and incarcerated at rates far exceeding their white counterparts. Black youth in Minnesota are more than eight times likelier than their white peers to be held in juvenile facilities — the 10th highest rate in the nation — despite studies showing few differences between white and Black youth in common categories of arrests for .

"Historically, we have allowed white children, or folks with means, to engage in developmentally appropriate behavior," said Sarah Davis, executive director of the Legal Rights Center in Minneapolis. "Our youth of color have gotten an entirely different system, which is criminalizing those behaviors and then funneling them deep into the adult justice system."

In 2005, several of Minnesota's largest counties signed on to the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI), an ambitious national effort to reform the juvenile system by shifting the emphasis from punishment to rehabilitation.

They adopted a screening tool to gauge a child's risk of reoffending or failure to show up for court. Designed to remove racial bias from the juvenile system, it also raised the threshold for who would be detained and for how long. Teens accused of low-level assaults and auto thefts, for example, no longer qualified for a bed in most instances.

Overall admission to juvenile detention centers in Minneapolis and St. Paul soon plummeted. Corrections officials became more reliant on to keep track of youth, even if some occasionally snipped off the ankle bracelets and vanished from oversight.

Over the past four years, between 20 to 25% of youth who were arrested for crimes in Hennepin and Ramsey counties were diverted away from formal court proceedings and into community-based programming such as mentoring, mental health counseling and jobs training.

Restorative justice practices, once rare, are now widespread. Counties are hiring outside providers to conduct group dialogues, or talking circles, in which youth are encouraged to confront the impact of their crimes on victims and the community.

But the effectiveness of these programs, largely operated by nonprofit agencies, is poorly understood. Many counties do not monitor what happens to children after they have been away from the formal court system. A Star Tribune survey of 44 counties, including all in the metro area, found that nearly half do not follow up to determine whether youth complete these community-based programs. And less than a third track recidivism rates, meaning most of the counties do not know if youth commit new crimes once they complete the programs.

Unlike many states, Minnesota lacks a central state agency tasked with overseeing juvenile justice programs, which has created a complicated patchwork of local rules. Individual corrections departments and prosecutors largely determine who qualifies for community-based programs and the intensity of services they receive. And data collection varies widely from county to county, which makes it difficult for policymakers to determine what programs are effective at reducing youth crime.

"At every stage of our youth justice system, people are making grave decisions about young people's lives without taking outcomes into account," said Danielle Lipow, senior associate at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a national children's advocacy and research nonprofit.

Pleading for intervention

On a bright afternoon days before Christmas, Cassie Carter left the construction site where she worked as a carpenter to make a phone call. She hoped it would save her son's life.

Just weeks earlier, Carter saw a troubling photo on Instagram of Jayden, grinning as he flashed a gang sign while standing shoulder-to-shoulder with an older-looking boy brandishing a handgun. On another occasion Carter discovered a bullet in the pocket of her son's pants.

From her car, Carter pleaded with the judge and county social workers for help in finding a safe shelter for Jayden. There, he could stabilize in a setting far removed from his gun-wielding friends and begin to transition back to school and family life. "I am terrified of losing my son, absolutely terrified," Carter said. "My son is on the streets. It's 20 degrees below. And he's robbing people to live."

But the remote hearing ended like so many others. County social workers and the judge recommended more in-home therapy and mentoring for a boy who was almost never home. Enraged, Carter yelled and pounded her fists against the steering wheel until her thin body, swallowed up by work overalls, sagged in defeat.

"Our kids are dying because they're not facing any consequences for their actions," she said. "No one seems to appreciate the urgency here."

Only three weeks later, Jayden was apprehended again — this time, for shoplifting and threatening someone with a weapon at a Roseville shopping mall. He was held several nights at a juvenile detention center before being released to a non-secure group home for youth in St. Paul. Within hours, Jayden slipped out of the home and was back roaming the streets of the East Side of St. Paul with his friends, Carter said.

Police and court records show that Jayden has been picked up more than a dozen times over the past two years. Last November, Jayden was among five teenagers caught in a stolen SUV after they led police on a dangerous chase near Stillwater. As he was taken into custody, Jayden dropped a bag of marijuana on the floor of a squad car, an arrest report says. Hours later, he was released and would vanish again.

Some nights, Carter drives the streets of St. Paul, looking for Jayden's face among the groups of teens she spots at street corners and bus stops. She gave up filing missing persons reports with police and county social service agencies because they were typically ignored.

Carter lamented the fact that Jayden had been missing for so long that his twin infant brothers, now 2 years old, barely recognize him.

"I cry every day over my son," Carter said, "because I've already lost two years of his life and I'm never getting those years back."

Officers see festering problem

Catherine Johnson struggled to control her emotions as she described how the wave of youth violence was affecting officers in her department, who are tasked with supervising troubled teens in the community after they have committed crimes.

"I will tell you that my probation officers have lost more youth to violence in the last year than in any year they can remember," said Johnson, a former Minneapolis police officer and director of Hennepin County's Department of Community Corrections and Rehabilitation. "They are devastated by the phone calls they are getting."

To Johnson, the deadly toll is a symptom of a long-festering problem. Too often, she said, youth are arrested and dropped off at juvenile detention centers, then released back to the community without being evaluated or connected with social services. They frequently reoffend, she said, and the cycle repeats until a child commits an offense serious enough to merit detention or supervised probation.

This revolving door became more pronounced during the pandemic, as children struggled with isolation and a lack of structured activities.

Putting fewer children behind bars was meant to be part of a broader package of reforms. Under the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, money saved by not incarcerating children was supposed to be redirected to mental health services, chemical dependency treatment and other programs to support children and keep them out of trouble.

But parents complain there are typically no consequences if their children do not participate in rehabilitative programs.

Tinikia Jones, of Richfield, said her teenage son was diverted to mental health counseling at age 15 after he began committing a series of minor thefts. When he quit after just a couple of therapy sessions, the provider never got in touch, she said. Her son's crimes have since escalated, and he now faces five felony charges related to a vicious carjacking on Christmas Eve, in which a woman was threatened at knife point and severely beaten.

"Right now, these kids aren't afraid of anybody," said Jones. "And why would they be? What do they have to fear if there's no one to hold them accountable?"

Some parents are so desperate for assistance that they are begging detention centers to hold their kids in custody, even for a short while.

In separate interviews, four mothers told the Star Tribune that staff at the Hennepin and Ramsey County juvenile detention centers refused to hold their sons, saying their crimes were not serious enough. The mothers, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, said they were warned their children would be considered "abandoned" and at risk of being placed in a temporary shelter if they were not picked up.

Hennepin and Ramsey County corrections officials say they are sometimes forced to refer a youth to child protective services because confining children who do not meet the detention threshold would violate their civil rights.

T'Lisa Williams, a restaurant worker from St. Paul, said she pleaded with staff at the juvenile detention center in St. Paul to hold her 13-year-old son, even for a few hours, when he started skipping school and acting out aggressively at home. She was told that he did not meet the criteria for custody. Soon after, he began carrying a handgun and now faces multiple felony charges, accused of beating and robbing an older woman at gunpoint before fleeing from police in a stolen car.

"No mother wants her child incarcerated, but we have to intervene before it becomes a crisis," said Williams. "I would rather my son face consequences now, when he can still be saved, than when he's an adult."

Unbearable loss

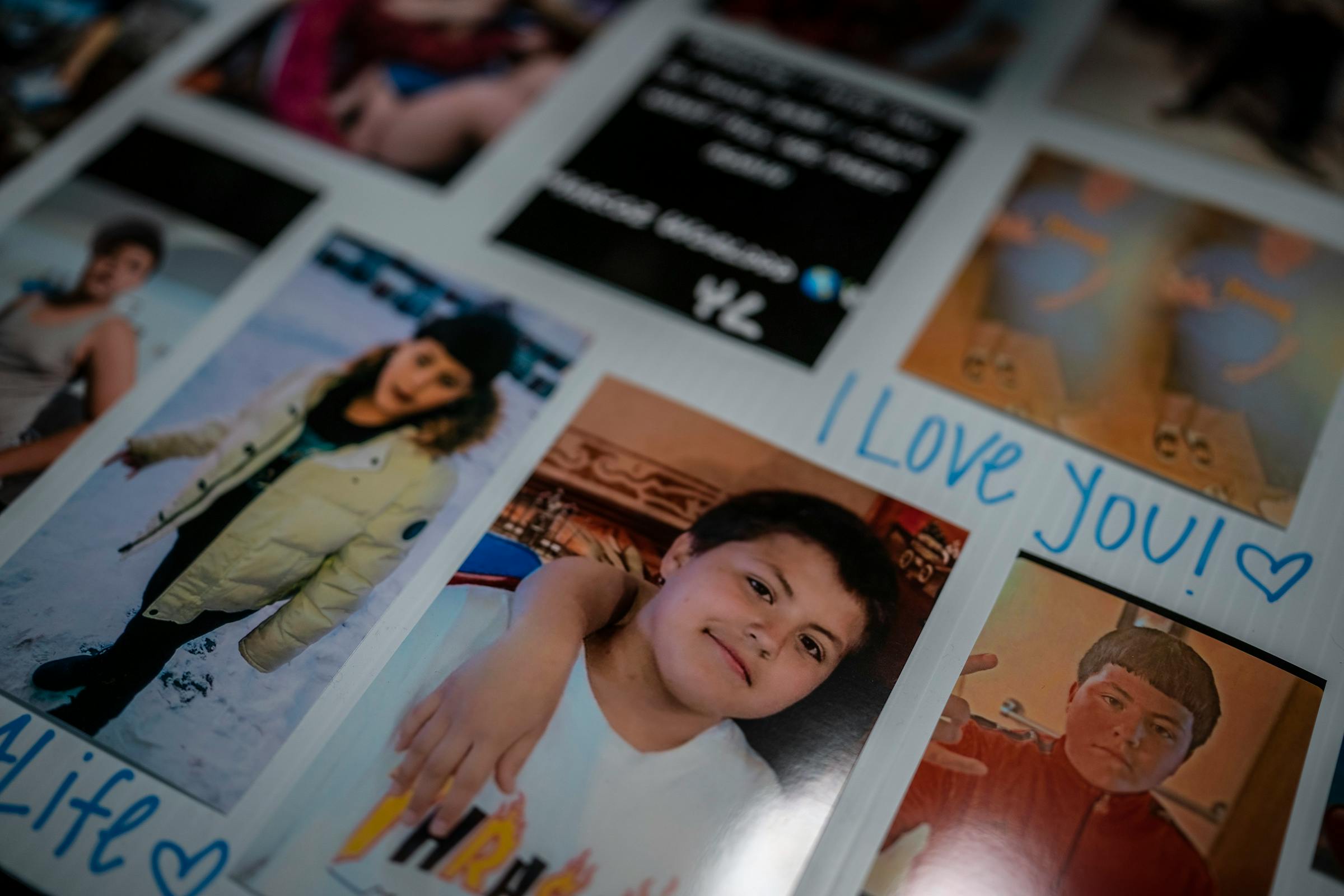

As dusk fell on a brisk winter evening, Tanya Gile gazed out her kitchen window at the deserted playground where her 14-year-old son Marcoz used to run, laugh and shoot baskets with his younger brothers. When she thought about how his life could have turned out, she remembered a short essay that Marcoz wrote in seventh grade.

"I have a dream of doing bigger things," he wrote, "and to have people look up to me."

The words would be read aloud at Marcoz's funeral.

On the fourth day of his first year in high school, Marcoz climbed into the back seat of a stolen SUV with five of his friends and asked to be taken home. His friends had other plans, and the car weaved erratically through rush-hour traffic and residential neighborhoods in Maplewood.

Ramsey County sheriff's deputies gave chase at speeds topping 100 mph until the car flew off the side of an embankment and severed a telephone pole.

Marcoz and another boy, 15-year-old Alyjah Thomas, of Oakdale died from injuries sustained in the crash.

Later, Gile learned that her son's last cries for help from the back of the crushed vehicle could be heard from blocks away. "My heart was ripped from my chest," Gile said. "Right then, my motivation to live, my willingness to tend to my other kids — my will to do anything — was gone."

Gile and five of her children live at Emma's Place, a complex of low-income townhouses scattered around a courtyard, playground and community center in Maplewood. The close-knit development serves families who were formerly homeless or those with parents who struggled with substance abuse. Known in the community as "Miss Tanya," Gile is the self-appointed guardian of Emma's Place, and she keeps a close watch on the dozens of children who live here.

She began noticing signs of trouble last spring. Her three sons — Marcoz, Nycio, 12, and Santino, 9 — and other neighborhood children began vanishing from Emma's Place for hours at a time, and then returning with new clothes and small weapons like knives and pepper spray, she said. Recognizing the items as stolen, Gile admonished the children and grounded her sons for weeks to their two-story townhouse.

But the crimes continued, and Gile pleaded with police for help in holding the children accountable. After not getting a response, she traveled up and down White Bear Avenue, a busy thoroughfare near her home, and urged shop owners to call her if they saw children from Emma's Place. Maplewood police records show that calls to the complex and the surrounding neighborhood reached a fever pitch last summer, with nearly two dozen reports of shoplifting, stolen cars and vandalism involving youth.

"It was spiraling out of control and you had to be watching the kids 24/7 to stop it," said Gile.

One event stands out in Gile's memory that, handled differently, might have altered the tragic course of events.

On a warm June afternoon, three months before Marcoz died, her younger son Nycio stole a car idling outside a drugstore just a short walk from Emma's Place. Though barely able to see over the steering wheel, Nycio drove the car through the neighborhood and abandoned the vehicle in a nearby subdivision. Before long, children were racing through the playground of Emma's Place, shouting about how Nycio had just stolen a car.

Gile, who was pulling weeds in her yard, flew into a rage and called the police on her own son.

Minutes later, a Maplewood police officer arrived at Emma's Place and questioned Nycio, who calmly escorted the officer and his mother through a field to the spot where he had left the stolen vehicle. The officer's body camera video then shows Gile pleading with the officer to put Nycio in handcuffs and take him into custody as a lesson. The officer could be heard laughing in the video before politely explaining to Gile that it was not worth the effort of bringing the child to the juvenile detention center.

"All it's going to do is inconvenience you," the officer said in front of Gile and her sons, according to the video. "Right now, if I take him down there, all they're going to do is book him in and call you to come get him."

During their exchange, Gile yelled a warning that would prove prophetic: "I'm gonna end up with a dead son!"

Gile believes the encounter that afternoon sent a dangerous message to her sons and other children in the community: that they could engage in criminal behavior without consequences. "I think that if the people we pay to protect and to serve our community had done their job, then my son would still be alive today," said Gile, breaking down in tears. "How do you watch kids steal cars and then tell them that nothing's going to happen to them?"

A spokesman for the Maplewood Police Department said officers lacked probable cause to arrest Nycio because the vehicle owner recovered the car before officers arrived, and a victim could not be identified.

Not far away, the 15-year-old teenager who drove the car that carried Marcoz to his death was living through a nightmare of his own.

Local police knew Mekhi, whose shock of tall hair makes him appear older than he is, as someone who went joy riding in stolen cars, sometimes streaming live videos of himself inside the vehicles, according to a search warrant. He attended the same high school as Marcoz, and both liked basketball and rap music.

Only a week before the fatal crash, Mekhi invited Marcoz to his father's apartment in St. Paul for dinner. Over plates of spaghetti and meatballs, Mekhi's father, Stevie Bryant, a maintenance technician and musician, steered the conversation toward the future, and what the two boys planned to do after graduation. At one point, Bryant pulled out a pencil and paper and sketched how they could buy property and eventually start a business.

"I was trying to get the boys to imagine a better life — a life away from all this chaos and violence," said Bryant, gesturing toward the street outside his window.

Those dreams were cut short. Hours after crashing the stolen car and running away, Mekhi appeared at the doorway of his father's apartment. Bryant recalled that his son collapsed on the floor of his living room, sobbing and repeating over and over, "Dad, I killed my friends, I killed my friends." Soon, Bryant's phone was buzzing with calls from the police looking for his son.

Mekhi spent much of the next three months in a cell at the juvenile detention center in St. Paul. On phone calls with his father, the boy described a recurring dream in which his two friends who died in the crash appeared by his bedside, urging Mekhi to come outside and play.

In December, Mekhi pleaded guilty to criminal vehicular homicide and was sentenced to at least six months at the juvenile facility in Red Wing. Bryant and his family said they were relieved by the sentence — hopeful that a prolonged period in a secure setting would enable the boy, who just turned 16, to get sustained mental health therapy.

"The guilt is tearing him apart," Bryant said.

In February, Bryant found a new apartment on the outer edge of the Twin Cities, far removed from their old neighborhood. Bryant said he hoped the move would help Mekhi make a "clean break" from his old friends and past behavior. No one would know their new address except for Mekhi's closest relatives.

"I told Mekhi, 'You owe it to your friend Marcoz and to everyone you hurt to become a great person,'" Bryant said. "Let's see some greatness. Otherwise, this is just another meaningless tragedy."

Fearing that his son was growing despondent, Bryant wrote and recorded a love song to Mekhi, hoping it would lift his son's spirits and keep him thinking of a brighter future. In a basement recording studio, Bryant belted out the gospel-like chorus over and over again, stretching out the harmony and the words until he had them just right.

"It won't be long

Until you get home

We'll be here

Don't you fear …"

Finally satisfied, Bryant wiped the sweat from his forehead and tucked the handwritten lyrics into his pocket.

Then he closed his eyes and swayed alone to the sound of his own voice, humming "It won't be long," until the lights went out in the studio.

Star Tribune intern Maya Miller contributed to this report.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported Paul Gazelka's title. He is former Minnesota Senate Majority Leader.

About this series

Juvenile Injustice is a Star Tribune special report examining how Minnesota's juvenile justice system is failing young people, families and victims of violence.

Part 1: Broken promises, shattered lives

The consequences can be

deadly when the juvenile

system fails to intervene in the lives of Minnesota's most troubled kids.

Part 2: Justice 'by ZIP code, not fairness'

Minnesota has no

uniform standards for who can

join diversion programs or what they offer.

Part 3: Nowhere to go for most troubled youth

As youth detention

centers close, Minnesota runs out of places to

rehabilitate kids who commit serious crimes.

Part 4: 'Back door to prison' steals precious time

Minor offenses often funnel Minnesota youth from extended probation into adult lockup.

Part 5: Laying down the law for youths

Minnesota's juvenile justice system is broken. Colorado shows how it could be better.

How we reported these stories

Star Tribune journalists spent more than a year examining hundreds of juvenile court cases dating back to 2018 that involved violent crimes, including shootings, aggravated robberies and homicides. Many of the young people charged in those incidents had committed previous offenses, leading us to ask whether Minnesota's juvenile justice system was fulfilling its core promise of rehabilitating youth while protecting public safety.

Our review of court records was limited in scope because most juvenile case records are confidential. In Minnesota, juvenile crime records are only accessible to the public if the offense is a felony and the youth was at least 16. In cases where a court document was not accessible, we relied on interviews and documents obtained from relatives, victims and public-records requests from local law enforcement agencies.

Gathering statewide data about the effectiveness of rehabilitation efforts is difficult because the youth justice system in Minnesota is highly fragmented. The programs and the process of redirecting youth from formal judicial processing (known as "diversion") vary widely between counties. To better understand how these programs work, we created a survey that was sent to all 87 counties. We received responses from programs in more than half of those counties, representing 85% of the state's juvenile population.

Many young people do not re-offend. The juvenile courts shield their identities because a public record of their crime could be a barrier to attending college, obtaining a job or renting an apartment. Through the course of this series, we identify minors only by a first name — and only when parents have specifically consented. Those publicly identified after their deaths are the lone exception to this rule.

Series credits

Reporting: Liz Sawyer, Chris Serres, MaryJo Webster and Maya Miller

Photography and video: Jerry Holt, Mark Vancleave, Cheryl Diaz Meyer, Christine Nguyen and Deb Pastner

Design and development: Bryan Brussee, Josh Penrod, Jamie Hutt, Josh Jones and Dave Braunger

Graphics: C.J. Sinner, Eddie Thomas, MaryJo Webster and Josh Jones

Editing: Eric Wieffering and Abby Simons

Copy editing: Catherine Preus and Amy Kuebelbeck

Audience engagement: Anna Ta, Nancy Yang, Ash Miller and Tom Horgen

Share your story

The Star Tribune is continuing to report on Minnesota's juvenile justice system. We would like to hear from judges, prosecutors, young people who have been involved in the juvenile justice system and their parents, and victims of crimes. Our reporters will not share your information without your explicit permission. You can reach Liz Sawyer at 612-673-4648 or at liz.sawyer@startribune.com, or via the encrypted messaging app Signal at 612-916-1443. Chris Serres is at 612-673-4308 or chris.serres@startribune.com, or on Signal at 612-910-7134.

Liz Sawyer covers Minneapolis crime and policing at the Star Tribune. Since joining the newspaper in 2014, she has reported extensively on Minnesota law enforcement, state prisons and the youth justice system.

liz.sawyer@startribune.com 612-673-4648Chris Serres is a staff writer for the Star Tribune who covers social services.

chris.serres@startribune.com 612-673-4308MaryJo Webster is the data editor, overseeing a team of data journalists and working with reporters to analyze data for stories across a wide range of topics.

maryjo.webster@startribune.com 612-673-1789 MaryJoWebster