Rehearsing for the Billboard Music Awards last month, Sounds of Blackness had finished the fourth or fifth take of their hit "Optimistic." Timing had to be precise for this network telecast. No room for error.

Before choir director Gary Hines could say "Let's do it again, like Mavis Staples says," he spotted something amiss in the circle of 20 singers.

"Stand by," he called out as he noticed tenor Steve (Smokey) Dinkins getting misty-eyed.

"Smoke, this has been a song that means a lot to me," Hines said. "It helps me out." Then he told the group that Dinkins recently lost his mother.

"Sorry," Dinkins blurted, wiping his face with a towel.

"That's the real deal," said Hines, noting how Dinkins had been moved by this song of hope in a crisis. "The Grammys are great, but this is the real deal."

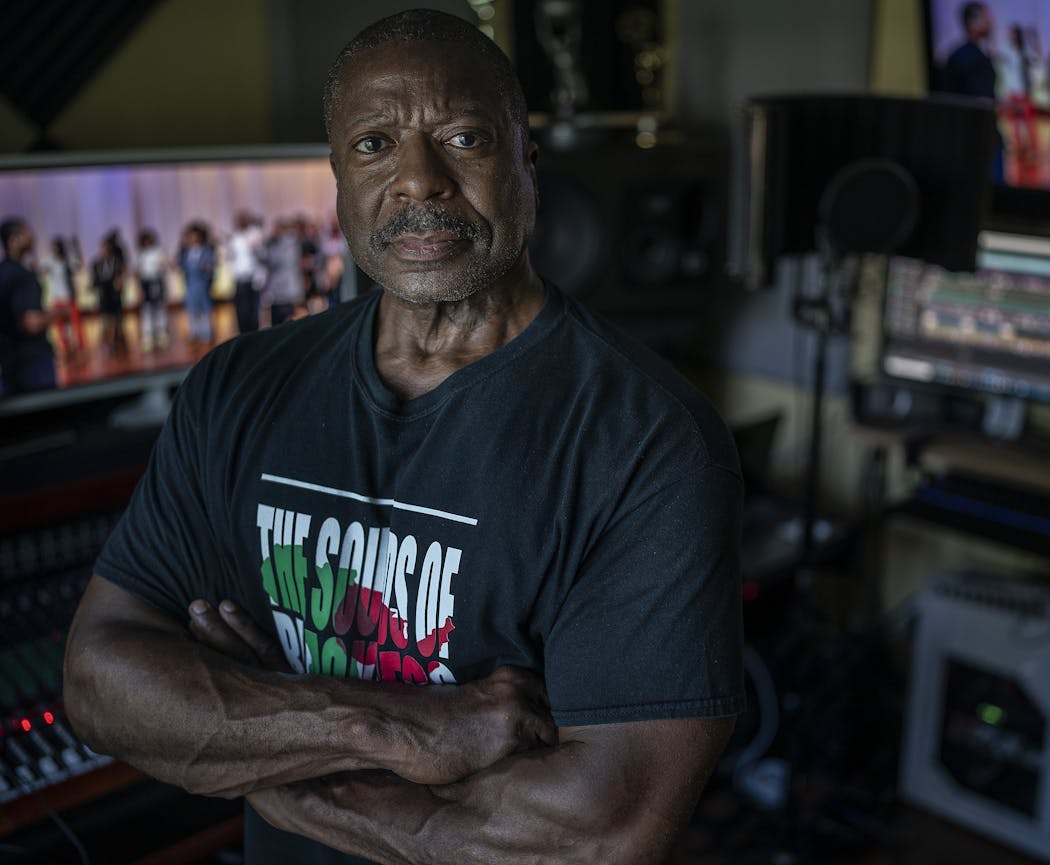

That's Hines — part teacher, part preacher, part psychologist, part father, part coach, part activist, part historian, part musical master, part drill sergeant.

For 50 years, he has led Sounds of Blackness, building them from a student choir at St. Paul's Macalester College to three-time Grammy winners who have raised their voices on five continents and worked with everyone from Aretha Franklin to Elton John.

In this new era of racial reckoning, those voices are louder than ever. Last summer, the group delivered "Sick and Tired," their fieriest anthem yet, with Hines echoing the words of 1960s civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer about "being sick and tired of being sick and tired."

This month, in conjunction with Juneteenth, the Sounds are offering "Time for Reparations," another Hines-penned salvo to be included in its forthcoming "Justice" package of commentary songs.

After George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police last year, Sounds of Blackness received dozens of offers to collaborate on a "let's hold hands" song. Hines is all about love and peace, but he didn't want to record a tune that would anesthetize the situation.

"That's not the message right now," Hines said the other day. "In the streets, there's righteous indignation and outrage, and that's got to be expressed in the music."

Soft-spoken but steel-willed

Even though the new batch of Sounds songs may be more aggressive than the trademark uplift of "Optimistic" and "Hold On (Change Is Coming)," Hines really hasn't changed in five decades.

Standing at an electric piano in front of his singers, mouthing the words, conducting with his bulging arms, Hines oozes quiet strength. He's polite and soft-spoken but steely, letting his music be his voice (he never sings solo in public).

"He's a humble visionary," said St. Paul producer and consultant Robin Hickman-Winfield, who has worked with Hines on programs at the Ordway, Twin Cities Public Television and elsewhere. "His spirit is so genuine. He's very intentional and he's very consistent. Gary is a brother who's committed to hope, healing and humanity."

And he's made Sounds of Blackness a Minnesota music institution that's heard round the world.

Take it from someone who not only met her husband in the Sounds in the 1970s but had her drummer son and singer daughter do stints in the group, as well.

"Gary hasn't changed in 50 years," said Moore by Four vocalist Ginger Commodore.

The ageless 69-year-old maestro is the same guy. Same even temperament. Same patience. He even maintains the buff body that helped him become Mr. Minnesota 40 years ago.

Hines lives in his forever south Minneapolis apartment in the Elliot Park neighborhood and drives the same old Chrysler Sebring with a Holy Bible on the rear deck. He leads rehearsals every Tuesday and Friday evening, just as he did at Macalester, dressed in a T-shirt and sweatpants — his offstage outfit since he quit his day job as a Minnesota Department of Human Rights investigator in 1988.

"We're still trying to figure out his youthfulness," said the sparkly lead singer of Sounds, Jamecia Bennett. "We're going to find whatever it is that he's eating or drinking. Because the man does not age."

Wait. One thing has changed, besides his recent knee replacement.

"He was way stricter then," observed Bennett, 49, who grew up in the group she officially joined 31 years ago. (Her mom, Ann Nesby, was the previous lead singer.)

Those fines for being late — even one minute — aren't levied anymore. People have jobs and children and other responsibilities. Sounds of Blackness is a volunteer-driven nonprofit that expects a minimum of 10 hours a week. Performers get paid for some appearances, including the Billboard Music Awards, but not for a recent event at George Floyd Square marking the one-year anniversary of Floyd's death, where they joined revered rapper Common for his Oscar-winning song "Glory."

The current members — 20 singers and 10 musicians, led by assistant director Billy Steele — hold a variety of jobs, from high school dean to touring guitarist with the Commodores.

But for Hines, Sounds of Blackness is a calling.

"It's definitely a ministry but not in the traditional sense of the word. Preacher, I am not. Pontificator, I probably am," he said over breakfast after his daily morning workout.

"I say it all the time: 'Sounds is a music message ministry.' We'll take 3M's title away from them."

Raised on 'music and muscle'

Growing up in the projects in Yonkers, N.Y., with two brothers and three sisters, Hines thought he'd be a lawyer. But he was preoccupied with two things: drumming and bodybuilding.

"Mom got me my first set of bongos at a secondhand store. I was just 4. Me and my brothers would pull out Mom's pots and pans and we'd beat on them. She took us to the Samuel H. Dow American Legion Drum Corps No. 1017. I was performing at age 5 with these grown men."

Hines and his brothers were also into fitness, inspired by the physiques of their dad and their drum leader as well as those Charles Atlas ads in the back of comic books.

"We'd see who could do the most pushups and situps. Music and muscle have always been there."

When Hines was 12, his family moved to Minneapolis after his mother, world-traveling singer Doris Hines, landed a two-week engagement that got extended to a full year.

He sang in church and school choirs, taught himself piano (he has perfect pitch), played football and threw discus at Minneapolis Central High School before heading to Macalester. As a freshman studying sociology, he took over leadership of Mac's two-year-old Black choir and gave them a new moniker and purpose.

Sounds of Blackness became regulars at Twin Cities events, but their profile exploded after becoming the first act signed by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis' Perspective Records.

Lewis grew fond of the Sounds when his older brother was a member.

"As a Black child, all through your education you never learn about who you are, where you're from, the music that was there," Lewis said. "The Sounds of Blackness have kind of been the bridge to that in the Black community. Their significance is ultra-important."

The Sounds' 1991 debut, "The Evolution of Gospel," led to the hits "Optimistic" (Lewis calls it "my favorite song we've written") and "The Pressure Part 1" (their first of two No. 1 dance triumphs), as well as their first Grammy.

Embracing everything from spirituals to hip-hop on their 11 albums (four of them for Perspective), the Sounds have picked up eight Stellar awards, three Grammys and an NAACP Image Award. They've performed at the Olympics, soccer's World Cup and the White House (five times).

For Hines, the brightest of many highlights was a trip to Ghana with Stevie Wonder in 1994.

After decades of singing about Africa, the Sounds finally visited their homeland. One afternoon they took an emotional tour of historic slave dungeons on the Atlantic coast, then had an unexpected encounter with celebrated percussionist Babatunde Olatunji.

"He stops us, and he recognizes me from 30 years earlier at Bryant Junior High School," Hines recalled with a smile. "The master Nigerian drummer who could play simultaneously in three time signatures. He was a minister and led us in a prayer of reconciliation right there on the beach."

Deferring to next generation

Hines' approach is all about education. He'll teach his minions as much about writer Langston Hughes and singer/guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe as about their vocal parts.

For newer members like Artisha Knight-Milon, 29, who joined Sounds in 2017, the imposing, stone-faced Hines can be a bit daunting.

"Before we went to Japan, Gary was on me like no one else, and I understood [that] because I was the newbie," she recalled. "It could be love/hate, but in the end it's all love because he pushes you past those mental blocks."

Hines may be demanding in an old-school way, but he welcomes the input of the group's next generation, whether it's 34-year-old tenor Rodney Fair about social-media marketing or Bennett about hip beats to reach millennials. And he often defers to Carrie Harrington, a senior member of 34 years, for choreography and feedback.

"He doesn't have that type of ego where 'only I get to make the decisions,' " she said.

Hitmaking producer Lewis thinks Hines is a natural born leader — direct yet diplomatic, stern yet fair. "He loves helping people achieve whatever their goals are," Lewis said. "He's a great messenger. I call him 'Doctor' because he's always trying to cure everything."

If Hines calls out a singer, he'll likely reach out to them privately to make sure they're OK. "He really do care," said Fair.

Having trouble with a relationship? Call Gary. Trouble at work? Ask Gary.

"When my sister passed in New Jersey, it was a dark time in my life," said Harrington. "He was there for me. He offered to fly to New Jersey."

In turn, the Sounds are protective of Hines. Whenever the women see some suspicious gold digger making eyes at him, they give him the stink eye. They've got his back.

Music may be his mistress, but Sounds of Blackness are his family, his big, crazy, extended family.

Hines sometimes regrets never having married and becoming a father. "I suck at relationships," he admitted.

His 30 "children" in Sounds of Blackness — and their dozens of predecessors — would disagree.

Twitter: @JonBream • 612-673-1719

Streetscapes

Critics' picks: The 12 best things to do and see in the Twin Cities this week

6 new foods worth trying at a Timberwolves game

The pandemic made writer Kate DiCamillo realize, 'I'm not going to get through this unless I have a fairy tale to write'