Rylie Perkins excelled as a softball player in high school. A standout pitcher who also could hit for power, she loved the sisterhood with her teammates at Centennial High School in Circle Pines — an experience she hoped to continue in college.

Twice she underwent wrist surgeries to remove cysts that could make pitching extremely painful, receiving speedy care without delays.

But the teenage athlete also struggled with anxiety and depression, and at 18, Perkins suffered from a worsening eating disorder as she tirelessly pursued dreams of playing at the collegiate level. She became consumed by the idea of restricting calories and worked out compulsively at the gym.

When Perkins eventually sought help for problems that included binge eating and bulimia, she discovered access to health care wasn't as easy as it had been for her physical injuries. After her initial assessment, she had to wait about three months for intensive outpatient therapy. Given the severity of her condition, she moved to a partial hospitalization program, but felt blindsided when her health insurer tried to deny coverage. Later, she couldn't find a psychiatrist who specializes in eating disorders.

"I've definitely found it more difficult to have access to mental health care," said Perkins, now a 22-year-old senior at Bethel University.

This experience, doctors say, is emblematic of how mental health patients across Minnesota often confront treatment barriers that are significantly harder to navigate than those for physical ailments.

It also points to a fundamental frustration with parity laws — statutes that prohibit health insurers from making it harder to obtain mental and behavioral health care than treatment for physical health conditions. For patients, it's almost impossible to know when their experiences qualify as violations.

"It's so complicated and difficult for consumers," said Kaye Pestaina, a vice president with the Kaiser Family Foundation. "With any particular treatment, there can be all kinds of nuances."

The elusiveness of parity

For more than a quarter century, patient struggles to obtain treatment for mental illness have prompted state and federal lawmakers to pass parity statutes in hopes of driving better access.

Passed in 2008, the landmark federal legislation on the subject was named in part for the late U.S. Sen. Paul Wellstone, D-Minn., who helped champion the effort.

The laws are critical, patient advocates say, yet better access to mental health care remains elusive due to a complex mix of factors that goes beyond what the statutes explicitly address. Violations by health plans are part of the problem; but there's debate about how frequently they occur and a recognition that the parity standard itself falls short of what's needed in some cases to truly drive improvements.

"Parity doesn't require that coverage for mental health or substance use disorder services is good or great — it just means that it can't be any worse than what we have for everything else," said Ezra Golberstein, a health policy researcher at the University of Minnesota.

Patient advocates say insurers, while avoiding the most obvious parity offenses, continue to violate laws amid a lack of enforcement by regulators.

Health plans argue that violations are few and far between and insist that access problems primarily stem from staffing shortages.

Mental health providers counter that patients would have more in-network options if insurers paid more for services and didn't make doctors and therapists jump through unnecessary hoops to get reimbursed. They add that stigma continues to play a role in access problems, since many patients are hesitant to seek care let alone demand coverage.

"The lack of parity is a reflection of how society values and thinks about mental health care," said Dr. Michael Trangle, a psychiatrist who is chair of the legislative committee at the Minnesota Psychiatric Society.

Concerns about mental health parity have intensified with the COVID-19 pandemic. Doctors are treating a surge of patients with anxiety disorders and depression, Trangle said, and are seeing more substance use disorders and opioid deaths. More teens and young adults are confronting eating disorders.

While trying to respond with telehealth services and larger networks, about 30% of employers said their health plans didn't have enough behavioral health providers to guarantee timely access to care, according to a national survey last year from the Kaiser Family Foundation. While half of employers characterized the size of their overall provider networks as "very broad," only 20% described their mental health networks that way.

Struggle to police insurers

Parity laws generally have helped in keeping insurers from imposing more stringent "quantitative" limits for mental health care, like higher copay and deductible fees, said Golberstein of the U.

But regulators have struggled to use the laws to police insurance rules known as "non-quantitative" restrictions. These are hard-to-detect problems such as tougher standards for determining the medical necessity of behavioral health services.

"It's been so difficult to implement because it's so hard to find the analogy on the medical side to make the point," said Pestaina of the Kaiser Family Foundation. "It's useful as a framework, but it has limits."

In late 2020, Congress amended the federal parity law so regulators could obtain reports from insurers on how they use non-quantitative treatment limits to restrict coverage for both mental and physical health care. The reports have become central to expanded enforcement efforts at the U.S. Department of Labor, which regulates most of the nation's largest employer health plans.

In early 2022, the Labor Department told Congress it had issued letters of initial non-compliance to 30 health plans following a review. As a result, health plans started making prospective changes — like covering two medicines for substance use disorder and expanding access to nutritional counseling for patients with eating disorders.

"We're seeing lots and lots of instances where, as a practical matter, mental health claimants and the families of mental health claimants who are trying to deal with the system are being forced, essentially, to navigate a bigger set of challenges to get the benefits they were promised than would be true on the medical surgical side," Timothy Hauser, deputy assistant secretary for program operations at the department's Employee Benefits Security Administration, told the Star Tribune. "This is a very, very real problem."

Health plans acknowledge there "were parity violations," said Pamela Greenberg, president and chief executive of the Association for Behavioral Health and Wellness, a trade group for some of the nation's largest insurers.

But Greenberg challenged the idea parity enforcement has lagged, arguing insurers need more guidance from the government on how to document compliance. "My sense is that [violations are] not widespread," she said.

In August 2021, the Labor Department announced a parity settlement with a division of Minnetonka-based UnitedHealth Group. The company agreed to pay about $2 million in penalties plus $13.6 million in restitution to participants and beneficiaries.

The department, working with the New York attorney general, found that for several years United reduced reimbursement rates for out-of-network mental health services, thereby overcharging patients, and flagged mental health treatments for utilization reviews, resulting in payment denials. The agencies also asserted that United failed to disclose information about these practices to patients.

UnitedHealth Group agreed to cease violations, the government said, and improve disclosures while committing to future compliance. The company did not grant an interview request, pointing to an earlier statement saying: "We are pleased to resolve these issues related to business practices no longer used by the company."

The issue was brought to light in part by litigation from Domna Antoniadis, an eating disorder patient in New York who filed a class action lawsuit in 2017.

After first seeking treatment at age 20, Antoniadis said she regularly submitted complaints to insurance regulators while pushing health plans for coverage. She decided to sue in hopes of winning change for other patients, too.

Now 37, Antoniadis encourages eating disorder patients and care providers to file formal complaints when they believe insurer decisions aren't fair. One problem, she says, is that taking on insurers can feel like an impossible challenge.

"You're like: 'Here's this billion-dollar company and here's this government agency and they're both telling me that I'm confused — and I have a mental illness and I'm overwhelmed because I have to take my kids to school and handle everything else. I guess I'm wrong,'" she said. "But you're probably not wrong. That's when you need to go back and use your voice to try again."

'There is no single metric'

Minnesota adopted a mental health parity law in the mid-1990s, yet a state task force in 2016 found parity still had not been achieved. Unlike with physical health care, many mental health services weren't available or covered until patients had severe symptoms, the task force said, adding that patients shouldn't have to wait six months for appointments with in-network providers.

Seven years later, patient advocates say the problems endure. Minnesota's departments of Commerce and Health, which regulate the insurance markets where individuals and smaller employers buy coverage, said changes with health plan offerings from year-to-year make measuring progress difficult.

"There is no single metric that allows us to definitively say that Minnesota has achieved parity," they said in a joint statement to the Star Tribune.

Ten states have imposed corrective actions on health plans and behavioral health organizations for parity violations or similar problems, according to Parity Track, a patient-advocacy website. Minnesota is not among them.

This spring, patient advocates are asking the Legislature to create within Commerce a new mental health parity and substance abuse accountability office. They also want new standards and penalties for evaluating whether health plans give patients an adequate network of mental health provider options.

When patients receive out-of-network care, they typically must pay more out of pocket, raising concerns about financial barriers to treatment. There have long been concerns that out-of-network care is a much bigger part of mental health than physical health treatment.

Before the pandemic, Minnesotans in certain employer health plans were three to four times more likely to seek out-of-network care for behavioral health needs than they were for physical health, according to a 2019 report from Milliman, a Seattle-based actuarial and consulting firm.

The study found Minnesota had a larger disparity than other states in terms of some health insurer payment rates to behavioral health specialists vs. reimbursements for primary care and medical-surgical specialists.

"When there's not parity in pay, you do see a lot of mental health professionals and providers going into private practice and only taking self-pay patients rather than participate in insurance networks," said Shauna Reitmeier, executive director of Alluma, a nonprofit mental health provider based in Crookston. "I believe that is one of the key consequences surrounding mental health services not having parity."

Mental health providers statewide are significantly underpaid compared to other providers with the same level of education, preparation, expertise and licensure, said Teri Fritsma, the lead health care workforce analyst at Minnesota Department of Health. Projections suggest shortages will get worse, Fritsma said, because the number of new graduates is not keeping pace with expected retirements in the field.

Providers also see a lack of parity show up in their battles with health insurers when seeking prior authorization for services or to satisfy special reviews for continued treatment, said Todd Archbold, the chief executive at PrairieCare, one of Minnesota's largest mental health providers for children.

Greenberg, of the trade group for health plans, said insurers want to provide a system of checks and balances to make sure recommended care fits with evidence for best practices.

Access problems point to the nature of mental illness and treatment. There's a lack of "social parity," Archbold said, as stigma and the fear of discrimination keep many patients from seeking help.

With mental illness, there are fewer tangible markers of improvement that insurers and care providers can pinpoint when deciding whether to continue care at different levels, said Lew Zeidner, vice president of mental health and addiction services at M Health Fairview. So, health plans can question — "sometimes validly, sometimes invalidly," Zeidner said — the value of investing in care.

"That sets the payers up to be skeptical of payment," he said. The dynamic is difficult because "most patients struggling with mental health have ambivalence about care."

'Depression swallowed me'

Rylie Perkins felt a sense of injustice when her health insurer, UnitedHealthcare, denied coverage for her continuing stay last year at the partial hospitalization program for eating disorders. On appeal, the insurer reversed the decision. Caregivers at the Emily Program helped transition Perkins back into intensive outpatient therapy within a few weeks.

Her three-month wait to begin eating disorder treatment was a consequence of too few mental health providers amid the increased demand for care, said Jillian Lampert, chief strategy officer at St. Paul-based Accanto Health, the company that runs the Emily Program.

And Perkins' lengthy search for a psychiatrist isn't uncommon, caregivers say, considering the limited number who specialize in eating disorders.

UnitedHealthcare says it has grown its mental health network since 2020.

Perkins, like many teenagers and young adults, lost out on celebrating milestone moments during the pandemic.

Her freshman year, after the spring season was cut short by the pandemic, "my depression swallowed me," she said. "We were all just alone and didn't have anything to do — nothing gave me any sort of joy."

More than a year later, she started exploring eating disorder treatment. The condition was reinforcing her anxiety, depression and feelings of inadequacy — a sense that she couldn't be loved given her body size. She thought about suicide.

"I was exhausted," Perkins said, "and I couldn't see a way out of it."

Compared with sports medicine, it's harder to know where to go for the right type of mental health care, she said. Plus, the stakes are higher for making a personal connection with your treatment provider.

Today, she credits treatment with putting her on the path to recovery, but is dismayed by reports about a growing sense of hopelessness in female students. She's sure that in many cases, the despair is driven by the self-destructive negative body image she's in the process of escaping.

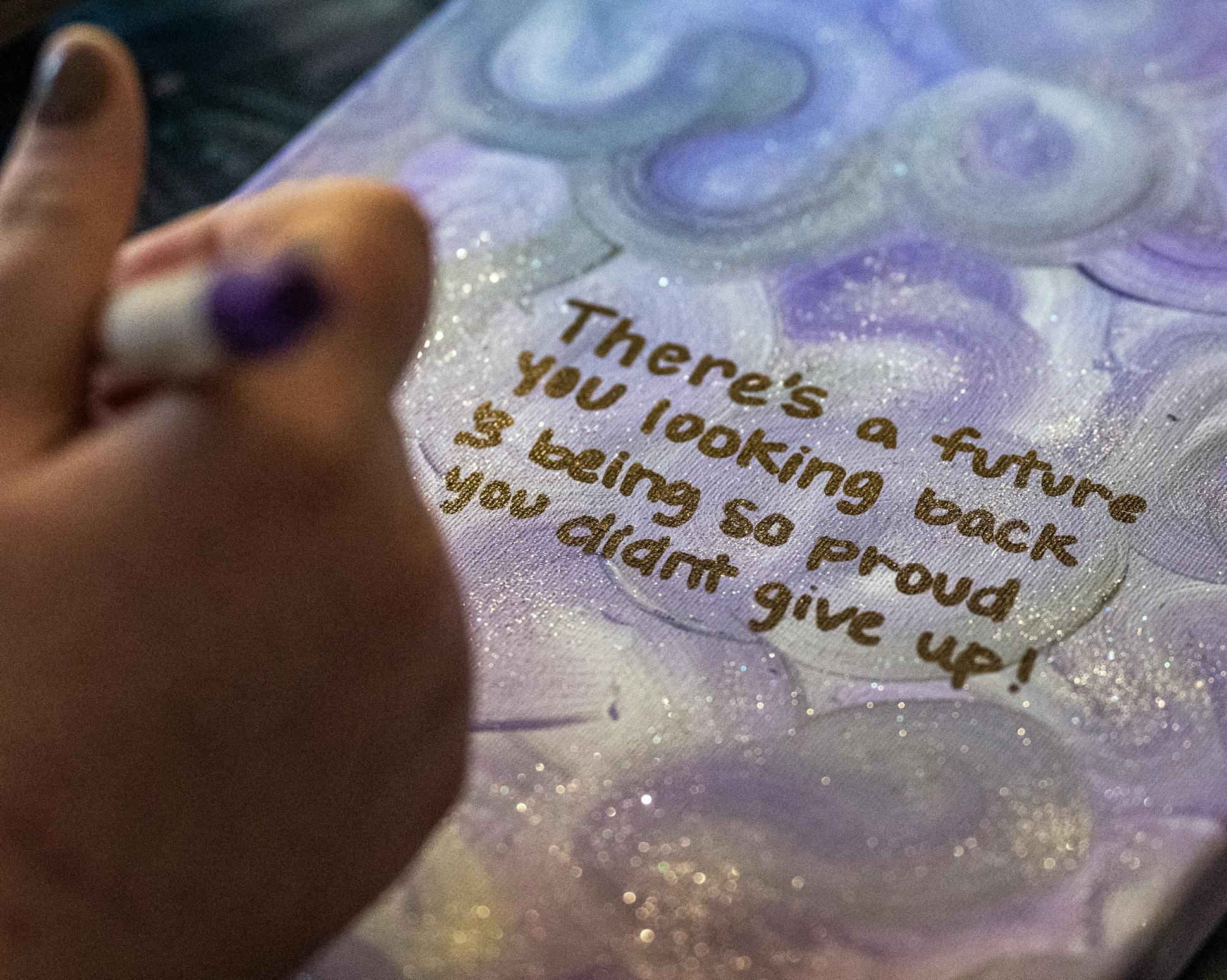

"I'm working towards acceptance that my body is a vessel," Perkins said, "and it's beautiful no matter what size, what shape it is."

Staff writer Christopher Snowbeck reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 Data Fellowship.