MARTINSBURG, W. Va.

A little girl killed by a stray bullet. Gang disputes resolved with deadly gunfire. Legally bought firearms that ended up in the hands of criminals.

The only place where the guns used in any crime nationwide can be traced back to their original buyer is inside this unassuming government building in the mountains west of the nation's capital.

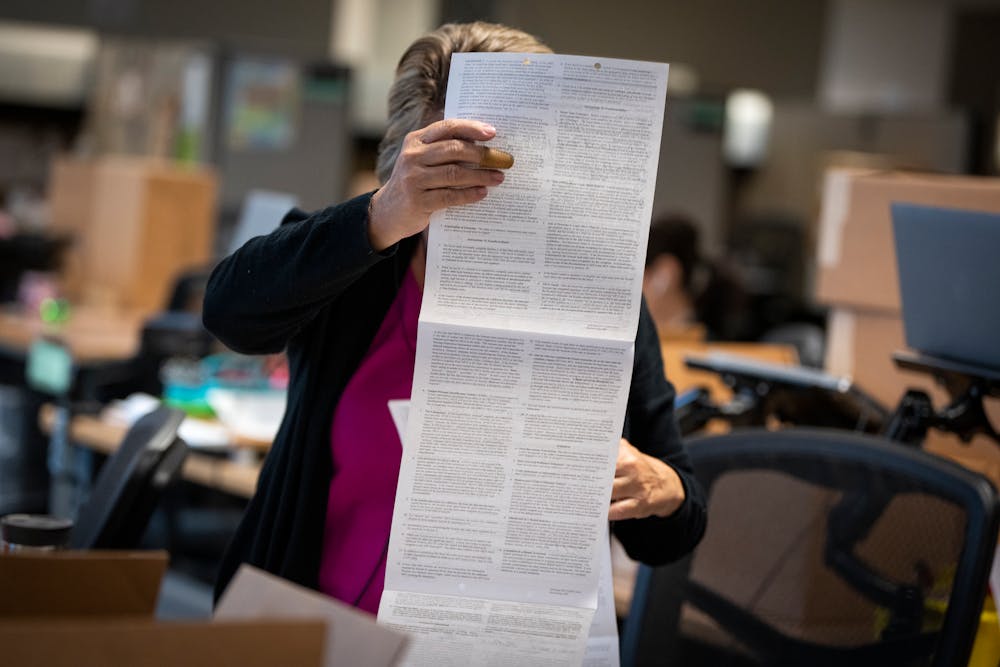

Here, an assembly line of workers leafs through thousands of paper records of gun sales. Others feed those documents through rapidly whirring scanners, and still others call gun makers and dealers, digging up leads for thousands of law enforcement agencies across the country.

More than 1,800 trace requests arrive daily.

"Every single trace is treated as if that might be the piece of information that helps law enforcement solve that crime," said Neil Troppman, who leads the National Tracing Center for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

But tight resources and congressionally imposed limitations make following the trail of the firearms used in crimes that much harder: the 900 million records held at the ATF, plus the millions still sent in each month by sellers who go out of business, must be converted into static images and pulled up by hand because a 1986 law bars the ATF from creating a searchable database for its gun records.

The agency, leaning on 65 full-time employees and 400 contractors, now sits on an 18-month backlog of documents needing to be processed.

This work continues as police seize and investigate more guns than ever before, and as investigators put a greater emphasis on studying the shell casings left behind after shootings.

In Minneapolis, investigators processed nearly 1,000 guns last year — up from 692 in 2019 — and more than 10,000 casings each of the past two years, more than double the total processed in 2019.

St. Paul police are now seizing more than 600 guns used in crimes per year since 2020. And statewide, the ATF recovered and traced 4,514 firearms linked to crimes in 2021, up more than 20% from 2017.

Until late last year, the ATF's backlog forced it to install 40 shipping containers in the Tracing Center parking lot, each holding 2,000 boxes of paper records. They had to be moved out of the center because their weight imperiled the building's structural integrity.

Despite these hurdles, this work — together with that of forensic scientists in Minnesota — is still generating important leads for federal prosecutors testing new strategies in a sprawling, ongoing Minneapolis gang case that unwound a yearslong campaign of gun violence. And it recently helped find the handgun used to kill 6-year-old Aniya Allen with a stray bullet in 2021, even as justice still eludes her family.

"These guns have really gotten into the hands of the wrong people," said K.G. Wilson, a longtime community activist who spent years aiding families of those killed by gunfire before Aniya, his granddaughter, was caught in the crossfire.

When a gun is used in a crime in Minnesota, police have two main paths for investigating the weapon. First, they can call up the ATF's Tracing Center to piece together the gun's history if it's in their possession and they know its serial number.

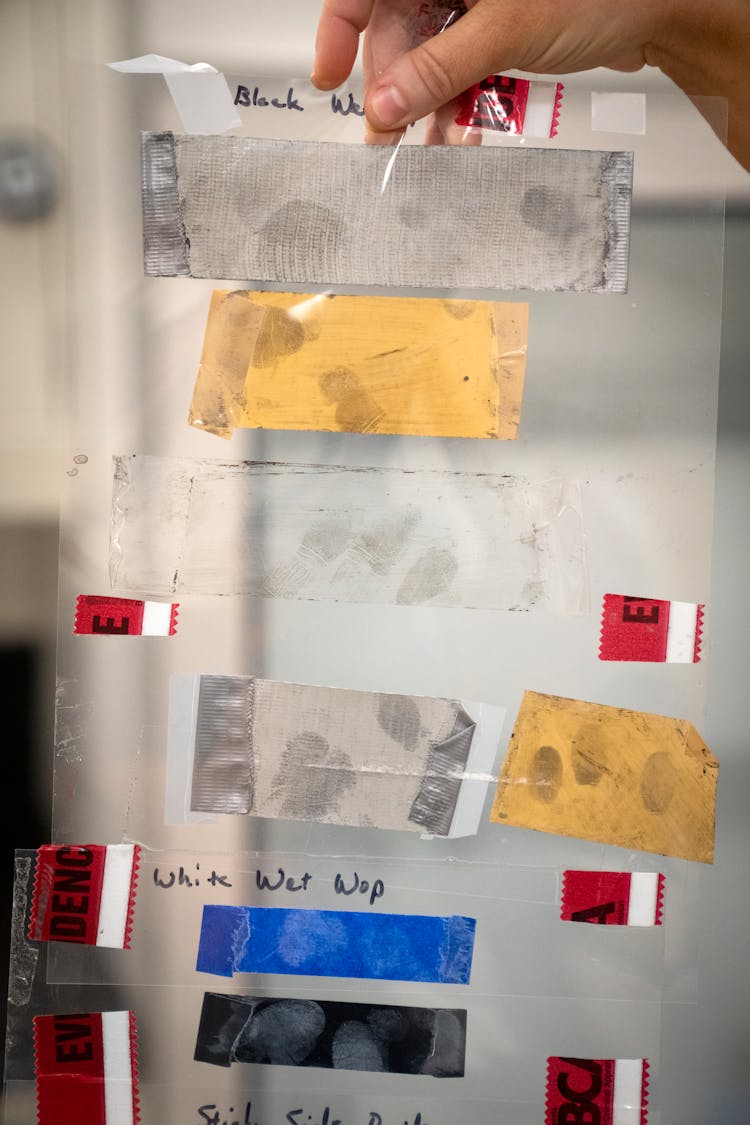

Forensic scientists in Minnesota and other states can also turn to high-powered microscopes and 3-D imaging to document thousands of spent cartridge casings left behind when a bullet is fired, and the unique markings each gun imprints on them. These "fingerprints" can help identify the gun used in a shooting and determine whether it is linked to other crimes.

That's how federal prosecutors built the ongoing racketeering case charging dozens of alleged members of the Bloods and Highs street gangs in Minneapolis. Using elevated charges approved by the Justice Department, prosecutors are linking together a trail of deadly shootings and other crimes that unfolded between 2014 and 2021.

Investigators in Minneapolis matched a single bullet removed from Aniya's body two years ago to a handgun retrieved from a man caught with fentanyl during a traffic stop last year. By further tracing that firearm, they concluded that the gun was probably among a dozen bought by a suspected straw purchaser still under investigation, according to unsealed court records.

Taken together, these methods are seen as the twin pillars used to solve crimes that often involve firearms changing hands many times.

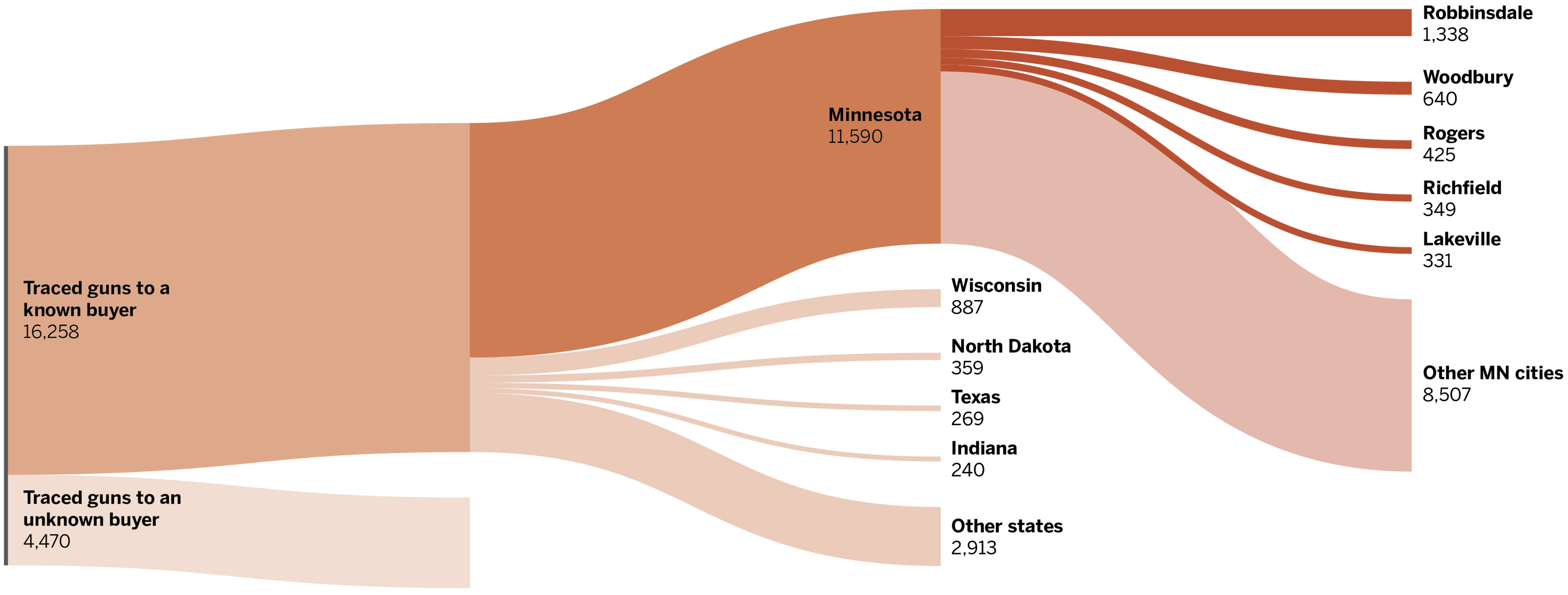

Tracing guns used in Minn. crimes

More than 20,000 firearms were recovered and tracked in Minnesota from 2017 to 2021. Of those, roughly 80% can be linked to known purchasers. Guns were traced to Robbinsdale as a point of origin more than any other city in Minnesota.

Yuqing Liu, Star Tribune

Source: ATF

Yuqing Liu, Star Tribune

Source: ATF

But there's a gulf between the two strategies: as one marshals the latest technological advances, the other is stuck in a tightly constricted lane.

Efforts to modernize the ATF Tracing Center failed amid a 2022 bipartisan push for new gun laws after mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo, N.Y. Objections have centered on the privacy rights of lawful gun owners not involved in criminal activity.

Requests nationwide for help tracing firearms have soared from 490,844 in 2020 to 623,654 last year — the highest on record. The ATF is forecasting a new high of 675,000 requests this year.

More than half of all trace requests from local police agencies involve records from closed businesses that are now kept by the ATF in West Virginia, Troppman said. Everything must go into a filing system to be searched by hand whenever police need help finding details about a gun linked to a crime.

If police need help probing the history of a gun bought from one of the country's 75,000 still-active dealers, Tracing Center workers will call the dealers to gather details about the gun's legal retail history.

Most requests are classified as "routine," but Troppman said the ATF fields up to 20 "urgent" trace requests per day, such as mass shootings, homicides or anything the requesting agency deems time-sensitive. Most urgent requests are completed within 48 hours.

"If we can shave a second or two off of every single trace, when you do the math, that's huge," Troppman said.

To capture the full picture of a gun's history, forensic scientists at several labs in Minnesota test-fire seized guns and examine the microscopic markings left behind on shell casings picked up from crime scenes.

At the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) in St. Paul, analysts use a metal water tank or devices that trap casings as they test fire and collect the spent casings for review. Because the gun's steel is harder than the metal bullets, it leaves a unique microscopic striation on the shell casing of each bullet fired.

BCA forensic scientist Travis Melland sat down one recent afternoon in St. Paul and fed one of those cartridge casings into a device connected to the National Integrated Ballistic Information Network (NIBIN). It captured three-dimensional images of the head stamp of the cartridge case, and picked up injector marks, firing pin impressions and images of the place where the gun struck the cartridge case cover.

The images are sent to the ATF's Correlation and Training Center in Alabama, where analysts and a specialized algorithm sift through thousands of such images daily to try to match them to other shootings. The ATF returns its "lead sheets" of these results to the agencies within 24 to 48 hours.

"That's one of the values of this being a national system but also having multiple agencies involved with it," said Steve Swenson, a forensic science supervisor at the BCA. "It allows that information sharing to really help develop those leads and turn those leads into actionable intelligence."

The BCA, which does this testing for nearly 400 law enforcement agencies, received nearly 1,000 firearms for review in 2022 — up from 390 in 2018.

"We see more people with guns than we've ever seen before," said Drew Evans, superintendent of the BCA.

William McCrary, special agent in charge of the ATF's St. Paul division, believes the increase in guns sent for review may reflect two developments: booming gun crime, but also local police agencies more often asking the ATF to help trace firearms.

Those two factors are behind the shrinking "time-to-crime" measurement — the amount of time between a gun's purchase and its use in a crime — recorded by the ATF, McCrary said. That average was 6.27 years in 2021, down from 7.34 in 2020 and 8.43 years in 2019. Minnesota's average is dropping at a rate nearly identical to the national trend.

Not long ago, NIBIN was often used to make the final confirmation that a particular gun was used in a crime, McCrary said. That meant that analysts often recorded hits long after a crime had been solved.

Now the ATF and other law enforcement prioritize recording and comparing ballistics evidence at the start of investigations.

"It gives the detectives something within 24 to 48 hours — as opposed to 24 to 48 months — to go on, and all that helps us break the shooting cycle, because today's victim is tomorrow's shooter is the next day's witness," McCrary said.

The Minneapolis Police Department is the only agency in the state with its own gun lab, and Shannon Johnson, the lab's director, said all shell casings linked to crimes are processed with its own NIBIN machine.

U.S. Attorney Andrew Luger has made cracking down on violent crime a priority in his second term as the top federal prosecutor in Minnesota.

Using NIBIN earlier in gun cases is becoming as routine as collecting DNA and fingerprints from suspects, said Luger, who leads a violent crime subcommittee of about 40 U.S. Attorneys from around the country.

"We try to focus on the most violent offenders — gang members and others who are associated with multiple shootings — to focus our attention and to focus our resources," Luger said. "NIBIN plays a critical role because we can fairly quickly determine how often this gun has been used in other shootings, where and when and if there are other cases being prosecuted related to those shootings. We can quickly determine who this shooter is associating with."

When gunfire claimed the lives of his Minneapolis neighbors, K.G. Wilson would rise at all hours to comfort their families. For six of those years as a peace activist in the city, Wilson had his granddaughter Aniya Allen to comfort him back home.

"As she started getting a little up in age, she thought she was becoming a big girl and I'd always tell her, 'you ain't no big girl. You're Papa's baby,'" recalls Wilson, who left behind life in a gang in the 1980s and 1990s for one of activism.

Aniya was in the back seat of a car when it got caught in the crossfire of a gun battle in north Minneapolis one evening in May 2021. A single bullet struck her in the head, killing her.

Now, Wilson's days start by checking his phone to see if Minneapolis homicide detectives can tell him "we got justice, we got him."

"And that hasn't happened for every day for two years," he said.

Wilson left Minneapolis two years ago. He now lives in St. Paul and works security at a Holiday gas station. He says he can no longer serve Minneapolis as a peace activist because so many of his days are clouded by anger and sadness.

He wears a black ballcap with ANIYA in bold white letters and freely hands out rubber wristbands that say "Justice For Aniya Allen."

According to recently unsealed federal search warrants, the ATF linked the gun used to kill Aniya to someone who bought 13 firearms around the Twin Cities metro area between March 2020 and June 2022: seven Glocks, four Tauruses, one Canik and one Rock Island Armory pistol.

The Star Tribune is not naming the suspected straw buyer because he has not been charged with a crime. But according to search warrant affidavits, he allegedly bought the Glock 19 pistol later used in the May 2021 shooting that killed Aniya and paralyzed a 19-year-old man.

MPD forensic scientists recovered discharged cartridge casings from an intersection and in an alley near the gun battle. A projectile removed from Aniya's body by the Hennepin County Medical Examiner was also consistent with a 9mm bullet.

Almost a year later, in March 2022, Minneapolis police recovered a Glock 9mm pistol during the arrest of Gregory Jones, who later pleaded guilty to fentanyl possession with intent to distribute. MPD police test-fired that gun and entered its cartridge casings into NIBIN. The results showed that the gun was linked to two shootings: Aniya's killing in May 2021 and a November 2020 shooting.

An MPD spokesman said that the investigation into Aniya's killing is ongoing. According to the court documents, investigators did not believe Jones was connected to the shooting but believed he obtained the Glock several months after it killed Aniya.

The use of NIBIN and gun tracing to zero in on the city's most prolific shooters was on full display with this spring's launch of the racketeering case charging 45 alleged members of two prominent Minneapolis street gangs.

Steve Dettelbach, the director of the ATF, traveled to Minnesota for the announcement of charges. He applauded the twin investigative approaches, saying "we can link together separate incidents and identify the trigger pullers better than ever before."

It is among the biggest gang cases ever prosecuted in Minnesota, and includes shootings dating back to 2014 involving at least two dozen victims.

Further charges are emerging against members of the Lows, another prominent Minneapolis gang locked in a violent rivalry with the Highs.

The current gang probe follows in the footsteps of a conspiracy case nearly a decade ago that marked the first time federal prosecutors in Minnesota used NIBIN to illustrate how shooters shared their guns.

That 2014 case charged 11 people with buying guns illegally and — like the ongoing prosecutions — involved accounts of the guns being passed around for use in crimes.

Marques Armstrong Jr. was one of those defendants and 19 at the time of his indictment. Before Armstrong was sentenced to more than four years in federal custody, the lead prosecutor in the case dubbed him a "virtual one-man crime wave," citing 14 pending criminal cases.

Not long after his release from prison, Armstrong resurfaced on law enforcement's radar — and he had clearly caught up with emerging illicit technologies that have made illegal guns more dangerous than ever.

One morning in late 2021, Armstrong led police and ATF agents on a high-speed pursuit in Roseville as they sought to arrest him for violating release conditions related to the federal case and a separate state assault conviction.

His Jeep jumped a curb, swiping a tree and spinning out. The collision broke an axle and flung off both rear tires.

Armstrong ran away from the Jeep and police chased him, eventually stopping him at gunpoint. Officers noticed that Armstrong wore an empty satchel, so they retraced his path through a wooded area nearby.

There they found a black Glock 26 firearm with a small pin attached to the rear of the gun's slide.

Investigators around the country have been recovering thousands of little devices just like the one attached to Armstrong's gun — "switches" or "auto sears" that are turning semi-automatic pistols into handheld machine guns.

Star Tribune staff writer Jeff Hargarten contributed to this story.

Credits

Reporting Stephen Montemayor and Jeff Hargarten

Photography Leila Navidi and Emily Johnson

Graphics Yuqing Liu and C.J. Sinner

Editing Eric Wieffering and Abby Simons

Copy Editing Catherine Preus

Design Bryan Brussee, Josh Jones and Josh Penrod

Correction: A previous version of this story should have said investigators matched a single bullet removed from Allen's body.