Hannah was 13 when she reported being raped by two men.

They were 21.

Police believed her, and spent 8 months building a case.

Prosecutors declined to charge the suspects.

Hannah’s father begged them to reconsider.

They declined again, saying they would be

unable to prove the case to a jury.

REJECTED BY THE

PROSECUTION

“I started to

see myself

as an object.”

Hannah Traaseth, 16

Student

Photographed in her

Wisconsin hometown

IN HER WORDS

Other sex assault victims in Minnesota share that feeling.

In Mankato, three women living at a facility for vulnerable adults in 2015 accused the building caretaker of sexually assaulting them. One of the women uses a wheelchair. Records show the suspect first denied to a detective that he had any sexual contact with the women, then later changed his story to say it happened, but that it was consensual.

Mankato Police sent the case to the Blue Earth County Attorney’s Office hoping for attempted rape charges. Charges were declined, with an attorney writing in the police report that the case could not be proved “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

In Minneapolis, Melissa Miyashiro was certain she had a confession from the man she accused of raping her, and that it would lead to criminal charges.

In a conversation recorded with a detective present, the man admitted more than once that he did not listen to Miyashiro when she told him to stop, according to the police file and audio provided to the Star Tribune.

“I’m falling apart,” she told him early in the call, her voice shaking. “I don’t understand why you didn’t listen to me when I said no.”

“I don’t know either,” he quickly responded, adding “It was completely wrong of me.”

Throughout the nearly eight-minute phone call, she continued to press him as he repeatedly admitted that he couldn’t explain his actions.

“You know without permission it’s rape. It’s what that is,” she said.

“I do,” he replied. “And I’ll never forgive myself for it.”

The Hennepin County Attorney’s Office declined to charge the man. Miyashiro said a victim advocate told her that prosecutors turned down the case because she didn’t fight back or leave the house.

‘I don’t understand why you didn’t listen to me when I said no’

With a detective present, Melissa “Rabbitt” Miyashiro recorded

a call with man she accused of rape. Listen below to parts of her call, which has been edited for

length.

Warning: contains graphic language.

0:00

2:49

The jury would say: “Why didn’t you leave?’ ” Miyashiro recalled the advocate telling her. “ ‘The defense would be able to put grains of doubt in the minds of the jury.’ ”

In a statement, Chief Deputy Hennepin County Attorney David Brown did not specifically say why charges were declined, but said two different reviews of the case “required a thorough evaluation of all the evidence included in this investigation. That included the recorded apology which was not an admission of this crime.”

In an interview shortly after the “Denied Justice” series launched, Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman said his office was examining 40 cases from this year that have not been charged; he also vowed to hire more prosecutors to help handle rape cases, and work more closely with law enforcement.

Prosecutors are not required to explain to victims or anyone else why they decide not to file charges in a case. Their communications with police are protected under attorney-client privilege. Many victims who spoke with the Star Tribune about their cases said they never got a chance to discuss the details of their case with prosecutors.

Ramsey County Attorney Choi said prosecutors are bound by an ethical obligation to not charge cases that they don’t believe they can prove beyond a reasonable doubt. The Hannah Traaseth case illustrates that because initial inconsistencies in her story would raise doubts in the mind of jurors, he added.

“Otherwise, we will have a system where prosecutors charge suspects because we merely think they are guilty without the evidence necessary to prove that to be true,” Choi said. “Certainly, prosecutors operating under this type of standard would at times convict the guilty and at times convict the innocent — an outcome none of us would want.”

Prosecutors often refer to the American Bar Association’s ethical standard for filing criminal charges, which says that should occur only if there’s probable cause of a crime and evidence that is “sufficient to support a conviction.” Roger Canaff, who prosecuted rapes for more than a dozen years in New York and Virginia and now trains law enforcement on the topic, said that standard should not be interpreted to mean that charges should be filed only when victory in court is likely.

“Prosecutors need to expand their view of what ‘evidence sufficient to support a conviction’ means,” Canaff said. “It can be the testimony of the victim, if it’s compelling enough.”

To sex crimes investigators, having to repeatedly tell rape victims that their case was rejected can be “demoralizing,” said Andy Skoogman, executive director of the Minnesota Chiefs of Police Association.

“This is exactly

why women don't

come forward.”

Melissa “Rabbitt” Miyashiro, 34

massage therapist

Standing in the room where

she

said she was raped

IN HER WORDS

DDan Drake, a detective in Rogers, Minn., has experienced that frustration.

In 2017, Dani Michels reported being raped by an ex-boyfriend. She was 15 at the time. He was 18.

“I believed the elements of the crime were there,” Drake said.

Michels said she was too drunk to consent to sex after a night of drinking at the man’s house. A witness confirmed that Michels was so drunk she was vomiting.

“I couldn’t hold up my head,” Michels told the Star Tribune.

According to Drake’s report, Michels said the man covered her mouth because she was too loud. She told Drake that she had fallen down and hit her head, and had scrapes on her arm.

Inside the News:

Investigating Rape

A joint podcast of the Star Tribune and WCCO Radio explores this investigation.

In his interview, the man told the detective that Michels “clearly wanted to have sex,” according to the report. He acknowledged in the report that he took Michels into the shower and that she was so drunk “that she was just dead weight.”

“He had sex with her while she was in an extremely intoxicated state by his own admission,” Drake wrote.

Drake sent the case to the office of Hennepin County Attorney Freeman. The detective told the teenager and her mother that he expected the ex-boyfriend to be charged.

Months later, Freeman’s office left a voice mail with the girl’s mother: They were declining to prosecute.

“When I heard that, I didn’t understand. I started crying,” Michels said.

When Drake called the prosecutor who reviewed the case, he said he was told that the county had a policy of not charging cases that involved juveniles who had previously been in a relationship with the accused.

“To be honest, I was pretty upset about it,” Drake said. “I thought there would be another victim, and sure enough there was.”

This time, the girl was 13.

In January, that girl reported that she was awakened by the same man as he raped her. When Drake questioned him again, he admitted to having sex with her and knowing that she was underage, according to a court complaint.

He was charged, convicted and sentenced to six months in jail and a stayed three-year prison sentence. He did not respond to a request seeking comment.

Freeman declined to discuss the case and referred inquiries to his chief deputy, David Brown.

Brown denied that the Hennepin County attorney rejects rape cases involving people who had a prior relationship. Citing victim privacy, he declined to talk specifically about Michels’ case.

He said in all cases, his office considers whether there is evidence to prove a case beyond a reasonable doubt.

“It’s wrong for us to go to trial if we don’t have enough evidence,” he said. “Letting a jury decide — that’s how you get wrongful convictions.”

Drake said he thinks the man was likely emboldened by the decision not to charge him in the Michels case.

“I think it’s reasonable to assume that if somebody doesn’t face consequences for their actions, it’s likely they might commit that action again.”

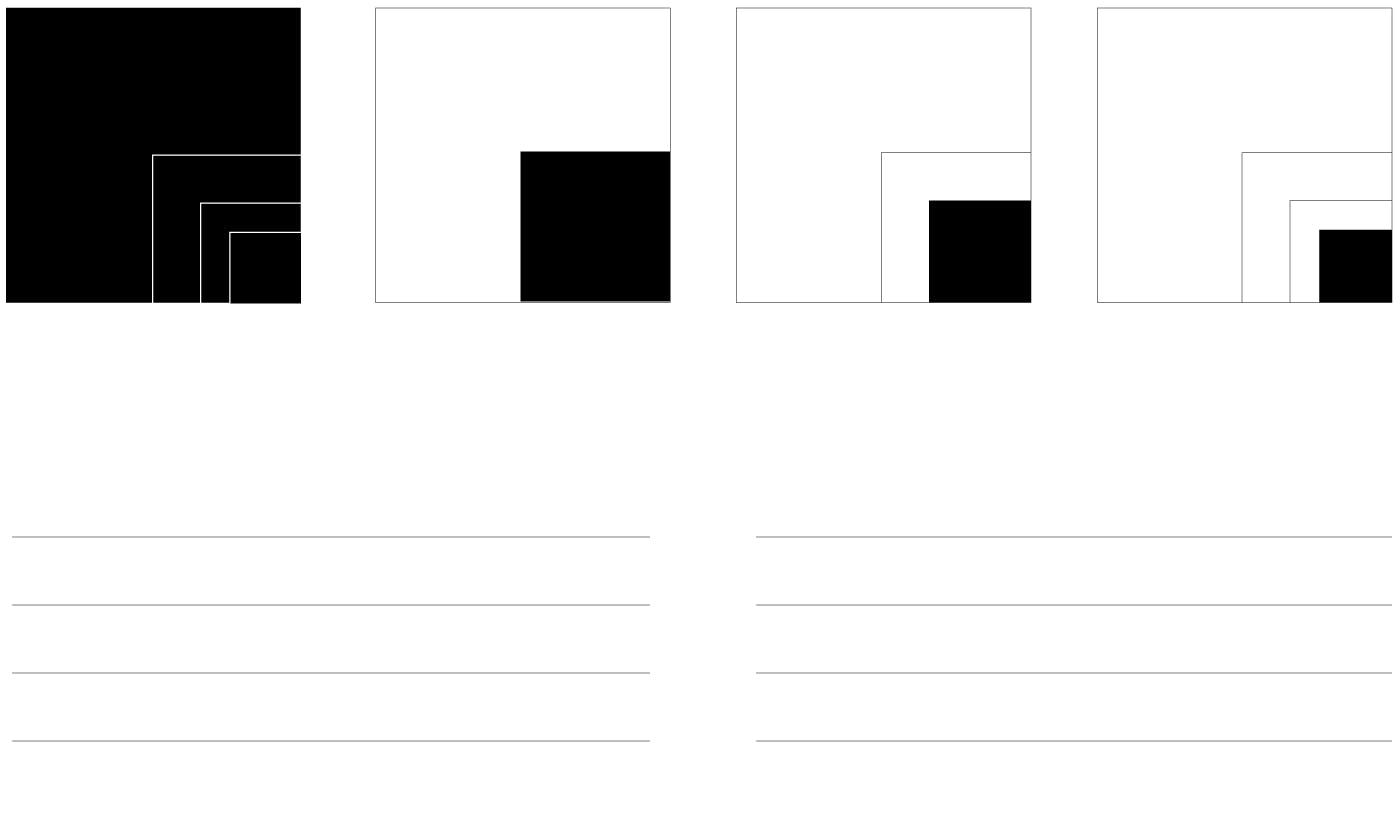

Failings in rape investigations

Most sexual assault cases never make it to a prosecutor's desk, and county attorneys reject half of them. A Star Tribune examination of more than 1,300 Minnesota cases found widespread shortcomings in basic investigative steps.

More than 1,300 cases

were analyzed.

26% of cases were

sent to prosecutors.

12% of cases resulted

in charges filed.

7% of cases ended in

conviction.

Cases not sent to prosecutors

Cases sent to prosecutors

Victim interviewed by an investigator

Named suspect interviewed

All potential witnesses interviewed

All potential evidence collected

25%

29%

41%

55%

Victim interviewed by an investigator

Named suspect interviewed

All potential witnesses interviewed

All potential evidence collected

83%

69%

60%

78%

Based on sexual assault cases filed in 2015 and 2016 and since closed by police in 20 Minnesota cities reporting the most sexual assaults. These updated results include 200 more cases than when the we first published our findings in July. We are still waiting for all the files we requested from five law enforcement agencies.

Source: Star Tribune research

TThe Star Tribune’s analysis of sexual assault cases filed in Minnesota in 2015 and 2016 found widespread failings in police investigations: evidence that was not collected, key witnesses or even suspects who were not interviewed; cases that were closed if the victim expressed any hesitation about going forward with a complaint.

In Traaseth’s case, investigators from two law enforcement agencies in different states moved aggressively to find the two men who she said raped her.

Her life had been difficult. She said she was sexually abused by a family friend when she was 9. Her mother died from cancer a year later. Depressed, she turned to pot, pills and alcohol. “Anything to take away the pain,” she said.

She started running away. She got into trouble with police when she was caught drinking.

On New Year’s Eve in 2015, while her father slept in the next room of their Wisconsin home, Traaseth texted a man she knew only through Facebook.

“I just don’t want to be alone,” she wrote him.

She sneaked out of her house and he picked her up. They picked up another man, who asked her how old she was. She lied and said she was 14. They took her to a home in Maplewood. They smoked pot and gave her something to drink that she said left her feeling paralyzed.

She begged to go home, but said they threatened to throw her in the snow. It was 16 degrees that night.

The two men took turns raping her for about two hours, she said. They laughed as she cried, repeatedly telling them no.

At about 5 that morning they drove her home. They warned her not to tell anyone about what happened, saying they knew where she lived.

She took the threat seriously, and said nothing. But her father knew something was wrong. She relented and told him she was raped. He called police.

In her first interview, Hannah Traaseth did not tell investigators all the details of what happened. She was worried for her safety, wanted to put it behind her, and she also feared they wouldn’t believe her because of her history of running away.

“I still need to investigate this,” the officer told her, according to his report. “I asked her to please tell me what happened.”

She told him that two men raped her at a party, but lied about where it occurred. She said it happened at the home of one of the suspects in another Wisconsin town. Police collected her clothes from that night, which she never washed.

She hoped police would move on. In most cases they do. This time they didn’t.

“It’s a juvenile sex assault,” said Veronica Koehler, a police detective in New Richmond, Wis., “I can’t not investigate.”

WWith Traaseth initially refusing to cooperate, Koehler got a warrant to search her Facebook account. She got the messages exchanged that night — and a name. But when police ran into dead ends, they went back to Traaseth . Eventually, with the encouragement of a school counselor, Traaseth told them what she said was the truth.

Koehler got a picture of the suspect’s Maplewood home and showed it to the teenager. She confirmed that’s where she had been taken.

Maplewood Police then took over. After interviewing Traaseth, detective Alesia Metry issued warrants for the suspects’ arrests. One refused to talk, and the other denied ever being around her. They were both released.

Three months later, DNA test results came back. Samples taken from Traaseth’s underwear matched those from the suspects. Police sent the case to the Ramsey County Attorney, thinking the men would be charged.

They never were, and the Traaseths demanded to know why. They were told that Hannah’s initial decision to lie about the details of that night hurt her case. Eventually, prosecutors wrote a letter that listed several reasons for not filing charges in Hannah’s case.

“If we were to pursue this case, all of those versions would have to be disclosed to the defense,” Assistant County Attorney Richard Dusterhoft wrote to the Traaseths in February this year. “She would be confronted and cross examined, in open court and in public, by each of her versions of events and her credibility would be impeached.”

‘I was just lost

in the dark.’

View video of women describing the experience of reporting their assaults to the authorities.

While he defended the decision in the Traaseth case, Choi has acknowledged problems with how police and prosecutors handle sexual assault cases in Ramsey County. A study by his office found that only 7 out of every 100 sex assault cases resulted in a conviction.

“A lot needs to change,” Choi said this spring. “We’re falling short on what really needs to happen, and it’s not on par with other types of crime.”

Still, Choi maintains that based on the evidence, a jury would not convict the men who Traaseth said had raped her. A trial wasn’t worth the risk it posed to her, he said.

Angry that prosecutors wouldn’t take his daughter’s case, Bradley Traaseth contacted state Rep. Marion O’Neill, whom he knew from high school.

O’Neill, who helped draft state rape laws, read through the case file and said she was baffled about why it wasn’t at least charged as statutory rape. She said Choi explained to her thatunder state law, a jury would acquit the suspects if they proved they believed she was 16. There could also be potential attacks by the defense on Traaseth’s credibility, he said. O’Neill wasn’t convinced.

“I have never been more disappointed in the whole system than I am with John Choi’s decision not to prosecute this case,” she said.

In a statement, Choi responded: “Rep. O’Neill’s personal and political opinion of this matter is not a luxury our office can consider given our ethical obligation to the law and the legal standards to which we must adhere when considering whether to charge any case — including this one.”

After the assault, Traaseth said she spiraled further into drug and alcohol abuse. One night when she was caught drinking, she bit an EMT called to the scene. At a group home, she bit a staff member. She was charged with felonies and committed to juvenile detention in October 2017.

She has been sober since then and worked over the summer at a part-time job helping to build low-income housing for a Wisconsin nonprofit. She returned home in September, went back to school and landed a part-time job.

Traaseth, now 16, said she is telling her story in the hopes it convinces other prosecutors to take on cases like hers.

She said she wishes Choi could recognize the pain and frustration she experienced.

“And then being rejected by the people that are supposed to help you,” her father said.