Bella can carry eight meals on four trays at one time.

She pauses when something or someone obstructs her way, waiting and politely telling them she's behind them. When she's not busy, she takes naps in the corner. And she meows a lot, especially when people pet her ears.

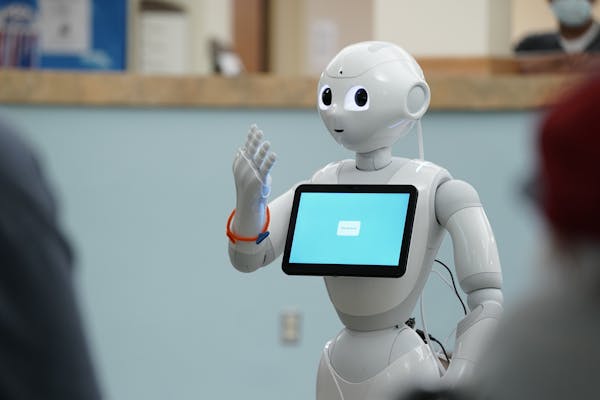

Bella isn't a super strong — albeit slightly strange — person. Nor is she a very talented cat. In fact, she's not really even a she at all.

Bella, short for BellaBot, is part of a growing trend where industries facing labor shortages look to automation to fill gaps or make jobs more appealing by freeing human workers from more mundane, physical tasks. Businesses from senior living centers to restaurants in Minnesota and the U.S., have started employing service robots like Bella.

The Commons on Marice, an assisted-living center in Eagan, brought Bella in about a year and a half ago when it was struggling post-pandemic to find enough workers to fully reopen its dining room.

Now back up to full staffing, it continues to lease the robot to send order tickets back to the kitchen and bring meals to people's tables, where a human worker meets it to serve the food.

"She saves us the trip of going back and forth, back and forth, to the kitchen," said Jorge Catano, the dining supervisor who gushed and chuckled as he showed off what Bella can do. "This way, we can spend more time with the residents in the dining room."

Bella delivers an average of 25 to 30 plates per shift and has made more than 700 trips through the past month, saving its employees more than 11 miles of steps. That's according to the Goodman Group, the Chaska-based company that manages the Eagan senior center and has introduced the dining-assistant robot to two other centers around the Twin Cities.

Meanwhile, some school districts in Minnesota have started using a different robot to help paint lines on sports fields, a time-consuming task that requires much precision.

Labor shortages, tight budgets and increased demand to use the fields meant it was hard for employees to keep up with marking and measuring everything, said Scott Kaminski, facilities operations manager for Mankato schools. The rushed work sometimes showed.

"When you've got a big Friday night football game, and your lines aren't straight, people send you pictures," he said.

He persuaded the district a few years ago to purchase the robot, which he said cost less than the price of hiring someone part time.

The robot, nicknamed Robbie, keeps the lines of the district's 20 or so soccer, football, baseball and softball fields crisp and bright. It uses GPS to mark the field and can also do custom logos and other designs for an end zone, for example.

"The best thing about it is it never calls in sick," Kaminski said. "It never complains."

But other hiccups can happen. The robot went offline last fall when it lost connectivity. The issue resolved after a change in cellular providers.

"Automation is not necessarily new," said Kevin McKinnon, interim commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED). "But it's an accelerating trend for businesses trying to expand productivity, increase precision and maximize their output."

It's also picked up speed as companies both large and small grapple with Minnesota's tight labor market, he added.

The state's labor force still has about 45,000 fewer workers compared with before the pandemic, partly due to accelerated retirements. The labor crunch is not expected to improve much in the coming years as the state's workforce continues to age.

There's more than two job openings for every unemployed person in Minnesota. While not quite as high as record levels from the year before, the state still had 185,000 job vacancies in the second quarter of 2022, according to DEED's latest survey released last week.

The four industries with the most openings — health care and social assistance; retail; hotels and restaurants; and manufacturing — are also some of areas where automation has grown, from robotic arms on a factory floor to QR codes at a restaurant.

In a recent Minnesota Chamber of Commerce survey of 150 businesses in manufacturing and related industries, more than half said they are planning to increase automation investments moderately or significantly in the next three to five years.

McKinnon added he's not seeing evidence automation is pushing people out of jobs, as is often the fear.

"Jobs are being repurposed," he said. "There's some additional training and other roles that people are taking in companies."

Liz Rammer, recently retired CEO of trade group Hospitality Minnesota, noted many restaurants and hotels pivoted to using technology more in part because of social-distancing concerns during the pandemic. But now, she's starting to see a move back in the other direction as some restaurants, for example, rely less on QR codes.

"This is an in-person industry," she said. "While there are certainly some things that can be offset to help with a labor shortage, at the end of the day, people want to be served by a person."

It depends on the venue, she added, noting customers have different expectations for quick service vs. fine dining.

One of the first restaurants to try a service robot in Minnesota was Sawatdee. The Thai eatery added robots to its locations in Minneapolis and Maple Grove in September 2021.

It's still using them as it continues to struggle with staffing, said co-owner Jenny Reilly, who added the robots are like an "extra set of hands."

"The robot can't do everything that a human can do," she said. "It can't take an order. It can't deliver drinks at all. It has a hard time doing soups."

One of the biggest benefits: lightening the carrying load for workers, especially those who work double shifts, she said.

But not everyone's a fan.

"Some customers really enjoy seeing it and take videos and are really enthusiastic," Reilly said. "... Other customers are like, 'Well, are we replacing the server?'"

The Mayo Clinic began experimenting with two service robots — Charlie and Will, after the hospital's founders — introduced in January at Charter House, its senior-living center in Rochester.

The robots primarily run a loop, transporting food from the kitchen to the dining room and returning with dirty dishes. While the robots have limitations, such as using elevators, the trial has gone well, leading Mayo to consider expanding them to other areas, said Kelly Nowicki, an operations administrator.

The robots have allowed workers to spend more time with residents, such as talking through dietary needs in more detail, she said.

While the center has frequent turnover, typical for the industry, Nowicki said the robots haven't reduced staffing. Rather, she said she hopes they've supported workers, leading to higher job satisfaction and retention.

"I really do think if we do this right, it will make our staff's life better," she said.

The Commons on Marice also recently added a vacuum robot for some of the main hallways, freeing custodial staff for more detailed cleaning in residents' rooms.

David Luhring, the center's executive director, said the robots have become an unexpected recruitment tool.

"The technology has helped us in hiring younger kids," he said. "When they come in and interview, and we say we use automation, they really like that."

Joanie Beckstrom, 77, one of the center's residents, said it seems like her food comes faster with Bella.

She also enjoys the robot's naps and catchphrases.

"It's really cute," said Beckstrom. "It's a treat having her around."

Bushel Boy, Minnesota's local tomato grower, sold

After 60 years, federal cuts shutting down Job Corps center in St. Paul

In a first, Minnesota doctors walk their own picket line, then hustle to see patients

It's harder to find a job this year, especially a corporate position