Five of the 10 children at Wendy Clark's day care left when the pandemic started, and it took a while to regain clients. The cost of cleaning supplies climbed even as she needed them more than ever. Then her family got COVID-19.

Then, shortly before she was forced to shutter her Shakopee home business for weeks of quarantine, Clark received a $4,500 grant from Scott County.

"That saved us," she said of the money that trickled down from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.

Minnesota counties, cities and towns got more than $1.1 billion from the relief package. Local governments spent the money on needs ranging from $2.5 million worth of personal protective equipment in Ramsey County to an $897 grant for a man making fishing lures in his basement in Walker.

The money has fed and housed people, and it sustained small businesses and nonprofits. Now, local leaders say, they are navigating a spike in COVID cases and another wave of business closures just as the dollars are drying up.

Cities had to spend their CARES Act funding by mid-November, and counties, except for Hennepin and Ramsey, must return any unused dollars to the state by Thursday.

Several local government officials said they don't expect Minnesota will get back much of the money it doled out. Instead, they are anxiously waiting for Congress to strike a deal on another round of aid and hoping state lawmakers pass a relief package in the meantime.

While some other states required local governments to submit reimbursement requests for federal funds, Minnesota distributed money directly to municipalities and counties based on their population and allowed them to use it as they saw fit within federal guidelines.

"Minnesota was fairly unique in the country in terms of the way they distributed the money," said Caitlin Humrickhouse, a senior manager at public accounting firm Baker Tilly, who helped some Minnesota counties and cities follow federal guidelines for the money. "A lot of other states were very, very restrictive, and so the money didn't really flow the way it was supposed to to counties and cities."

Unusual local uses

After Minnesota received the money in May there was a couple-month delay as state leaders debated how to divvy it up. That was relatively quick compared with other states, Humrickhouse said. Then there was a mad dash as local governments decided how to use the influx of cash.

Much of the money has gone to predictable needs, like supporting more than 5,000 businesses and upgrading technology so government employees can work from home. But some communities have found unusual ways to help residents weather the pandemic and respond to unexpected losses.

At Pine County Technical and Community College, 110 students have gotten free courses through a new "work fast" program that administrators developed during the pandemic and the county helped fund with CARES Act dollars.

"There's 110 different stories in these programs," said Joe Mulford, the school's president.

One student has been a bartender for years, but the bar she works at has been closed on and off during the pandemic, Mulford said. She decided to refresh her Microsoft, Zoom and other technology skills to get a job working from home.

Another woman got her nursing assistant certification so she could care for her mother-in-law instead of moving her into a long-term care facility, he said, while a farmer took a machining class so he could supplement his income by fixing or creating parts for old farm equipment.

In northern Minnesota, Verso Corp. closed its Duluth paper mill because of a lack of demand during the pandemic. It was a financial hit that rippled across the timber industry. So St. Louis, Itasca, Koochiching and Lake counties devoted hundreds of thousands of federal dollars to struggling loggers.

"I feel for these small logging businesses, because they are not working on a lot of profit margin" with expensive equipment and large upfront timber costs, said Jason Meyer, St. Louis County's deputy land and minerals director. "Frankly, if we didn't get dollars like this I think we'd be losing a lot more of our small businesses up here."

In rural Sylvan Township in Cass County, Lisa Paxton's grandsons were struggling to interact with their teacher and classmates online with their DSL internet connection. She surveyed neighbors and heard similar stories from students, business owners and people who needed telemedicine. They made a pitch for CARES Act funds and got $140,000 to secure high-speed broadband access for at least 24 households, Paxton said.

Housing insecurity has been a major issue in Ramsey and Hennepin counties, where officials have spent millions to expand and retrofit homeless shelters and house people in hotels.

A "COVID cliff" is coming as federal funding runs out this month, said Tracy Berglund, senior director of housing stability at Catholic Charities. She said there's a plan to ensure hotels remain available into the spring, "but this is a heavy load for local government to take on, so we need more federal funding."

Hennepin and Ramsey have a slightly different situation from the state's other 85 counties. They received a combined $317 million directly from the federal government. Money for the other counties was funneled through the state, as were dollars for cities and towns. The two largest counties and state government have until Dec. 30 to use CARES Act money.

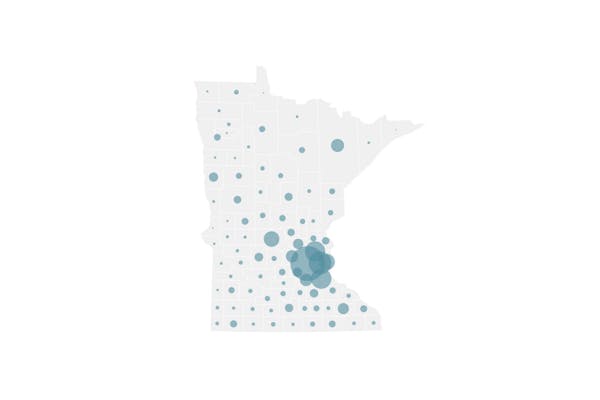

Every Minnesota county and 1,530 cities and townships had gotten some of the federal aid as of Sept. 15. Twelve cities and 261 towns were eligible for assistance but did not ask for the money, according to state budget officials. So the state distributed $837.7 million of the nearly $841.5 million it designated for local governments.

Some governments, like St. Louis County, hired outside groups like Baker Tilly to navigate the shifting regulations and design business assistance programs on the fly. Others, like Cass County, had their own employees handle it.

Rules kept shifting

The rules weren't always clear, Humrickhouse said. Sometimes the state's interpretation conflicted with the U.S. Treasury's, she said, and the federal government was making clarifications about how to use the money through the end of October.

"It was sort of this whiplash for cities and counties about how they could use that money," she said.

Minnesota's decision to give so much latitude to local governments could lead to issues if municipal officials did not follow spending parameters, Humrickhouse said.

Communities that spent more than $750,000 of federal money in a year must be audited by the state auditor or an accounting firm, said Ellen Anderson, a spokeswoman for Minnesota's COVID-19 Response Accountability Office. The U.S. Treasury Office of the Inspector General can also review any local government, Anderson said, but the timing of those audits — or even if they will happen — is unknown.

But the direct aid to counties and cities allowed locals to easily tailor the money to specific needs. In Cass County, administrator Josh Stevenson said, that included removing oak banisters in their courtroom so people could be socially distant, and creating a grant program where any type of business could get help. County commissioners even went door to door handing out grant applications.

"We got all kind of interesting requests," Stevenson said. "We helped 45 different businesses, 11 nonprofits and one of our joint powers partners. Our money got spread out significantly across the community."

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?