Minnesota school leaders, now with the state's long-awaited school reopening plan in hand, are in a six-week sprint toward an unrecognizable academic year.

The plan released by Gov. Tim Walz offered a lengthy list of metrics and requirements for opening and operating schools during the COVID-19 pandemic, but its flexibility — and the variability of the virus itself — means schools are still wading through a long list of decisions.

Over the next few weeks, they will have to explain the situation to parents and quickly determine how many intend to send their children back to school, if that's an option. They need to sort out how many teachers will ask to teach at home because of their own health risks, and whether they'll have enough bus drivers, substitute teachers and cafeteria workers. There will be a flurry of special school board meetings, calls to local health and emergency management officials, and an anxious wait to see if virus cases increase and upset districts' reopening plans at the last minute.

In far northern Minnesota, where the virus has spread at a lower rate than elsewhere in the state, Tom Jerome, superintendent of the Roseau Public School District, said school officials are moving forward with plans to fully reopen — but know a great deal of work remains before that can happen.

"Things have become very real, very quickly," he said.

Minnesota's reopening plan is built around state virus-tracking data, with school districts and charter schools being able to consider bringing students back only if cases in their counties remain below specific levels.

A full return to in-person classes, for example, could be considered if there are fewer than 10 COVID-19 cases per 10,000 residents over a 14-day period. At the other end of the spectrum, counties with more than 50 cases per 10,000 residents are likely to have to keep schools closed and opt for distance learning. In between those levels, the state has set standards for various combinations of "hybrid" learning, with students attending classes part time and spending the rest of the week learning at home.

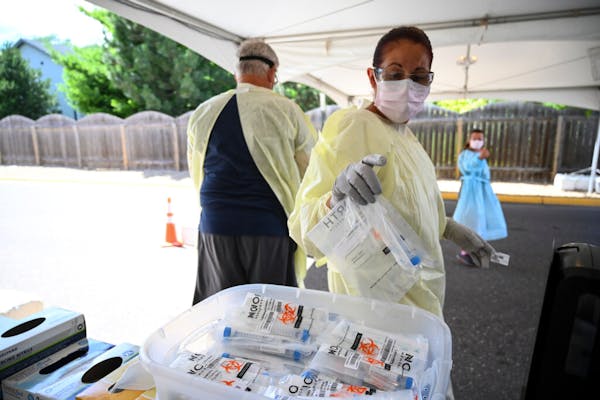

But that's only the beginning; even if schools meet those thresholds, they must still be able to show state officials that they have space to keep students and staff physically distanced, buildings with proper ventilation, vigorous cleaning protocols and processes to ensure students and staff are wearing masks and reporting when they feel ill.

Following Walz's announcement Thursday, many districts sent messages to parents that outlined the basics of the state's direction — and pleaded for patience as administrators and school boards scramble to work out the fine details.

In southwest Minnesota, home to the three counties whose recent virus spikes place them in the worst position to reopen schools under the state's metrics, Loy Woelber, superintendent of the Westbrook Walnut Grove, Fulda and Lake Benton school districts, posted on a district website that he's still hoping to avoid distance learning. He said local schools may have to juggle their plans multiple times through the year, and he and school officials would be "meeting intensely" in the coming week to sort out a strategy.

"It's overwhelming to say the least," he wrote.

Edina Public Schools Superintendent John Schultz spent the day after Walz's announcement in back-to-back meetings and on phone calls with school staff, making plans to start the year with all grade levels in a hybrid format. He said the district is formulating ideas for what student and teacher schedules will look like, but plenty of questions remain, from how bus routes will be redrawn to where and how the district will provide child care, both for children of critical workers and for students who need supervision on days they are scheduled for distance learning.

Schultz said parents would be contacted within a week with a request to decide whether their children will attend school for hybrid instruction or stay home full time.

"We'll be asking the parents to register and make a commitment each semester," he said.

In the Elk River school district, Superintendent Daniel Bittman posted a message to parents online, expressing frustration that the district's goal of fully reopening could be off the table — and that the district wouldn't know for sure until late August. The district spans five counties, including some where cases of the virus are now above levels permitted for face-to-face instruction.

The district plans to notify parents about whether school will be in person, online, or a combination of both on Aug. 21 — 2 ½ weeks before the first day of school.

"We recognize how inconvenient this late deadline is for families and apologize for the inconvenience," Bittman wrote.

At least two districts, Minneapolis and St. Paul, have decided to avoid some of the uncertainty by making plans to begin the year with distance learning. Leaders of both districts told parents last week that they intend to start the year online.

Teachers waiting to learn where and how they'll hold classes this year are anticipating a hectic run-up to the first day of school. Most are busy making lesson plans to deliver in person and online, unsure if they'll do one or the other, or both at the same time. They're wondering about the logistics of the state requirements: How much of the extra classroom cleaning will they be expected to do, and when? How will the state distribute the masks it has promised for all teachers and students?

Amy Aho, a speech language pathologist at a Brainerd elementary school, is trying to strategize about how she'll work with students wearing masks; being able to see how students move their mouths and articulate words is a critical part of her work. She's also wondering how she fits in plans to keep students and teachers separated into groups that stick together all day to avoid spreading the virus further. In a typical year, she's in and out of different classrooms all day.

Getting a plan from the state has helped sort out some of the big-picture issues of reopening, she said, but it presented new challenges, too.

"I don't know that the number of questions has decreased, but the questions have changed," Aho said.

Jessie Holm, a high school math teacher in Hastings, said she didn't sleep much the night after Walz unveiled the reopening plans. She tossed and turned, wondering about how the state and local districts will ensure schools have enough cleaning supplies and masks. She worried about how her students might feel stress about catching the virus and passing it to a teacher or a family member with a high risk of complications. She thought about the frenzied transition to distance learning last spring, and how districts struggled to stay connected to some students or communicate with families about what was going on.

"There's a lot that has to happen in the next [few] weeks," she said, "and that seems insurmountable at times."

Erin Golden • 612-673-4790

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?