Minnesota school districts are preparing to lay off teachers, drop programs and increase class sizes as they begin to feel the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their budgets.

Across the state, districts that saw their costs surge and enrollment drop during the pandemic school year are drawing down on their reserves and finalizing millions of dollars in cuts. With state lawmakers in a stalemate over school funding and budget deadlines approaching, many schools have begun sending out layoff notices, in some cases by the dozens.

But as they reduce their budgets for the declines of the pandemic school year, district leaders fear they're setting things off-balance for next year. As the pandemic recedes, thousands of students who left or delayed their start in public schools this year are expected to show up — to buildings staffed with fewer teachers.

"Right now school districts are laying off staff that they may desperately need in the fall," said Deb Henton, executive director of the Minnesota Association of School Administrators.

In the South Washington County school district, facing a $9 million budget gap, cuts for next year include 150 teaching positions plus some administrators, school nurses and classroom paraprofessionals. In Shakopee, the district is cutting 57 teaching jobs and raising its class-size targets. In Grand Rapids in northern Minnesota, Superintendent Matt Grose said the district is still finalizing exactly where to slice about $2 million from its budget, but he said it's clear a significant portion of it will come from staff cuts.

"There's no way to get to a number like $2 million without it affecting people," he said.

Though each school district came into the pandemic in a different financial situation, the financial pains it has caused are nearly universal.

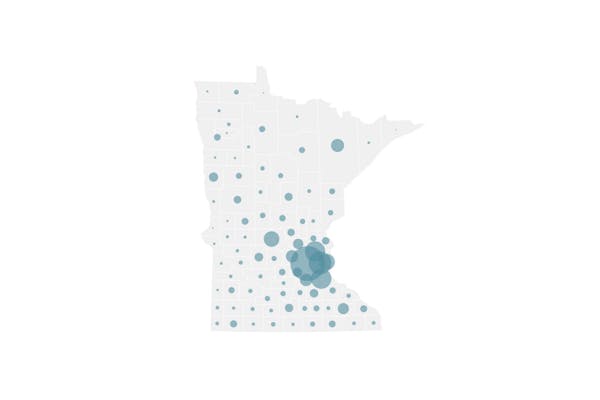

Statewide, public school enrollment fell by 2% this year as many families opted for private schools or home schooling or delayed their kindergartners' formal start to school. Because each student brings with them about $10,000 in state funding, the loss of even a few students in a small district — or hundreds in larger ones — added up quickly.

In the South Washington County district, for example, this year's enrollment was down by more than 300 students — and down closer to 500 from where the district had expected to be, because of a previous trend of enrollment growth.

"We're hoping the kindergarten class will be higher [next] year," said Dan Pyan, the district's finance director. "Time will tell on that, but that's a big revenue factor for us."

At the same time, districts also lost out on a different pot of state funding for schools known as compensatory funding, which is set aside to help students struggling academically. That money is handed out to schools based on the number of students who qualify for free and reduced lunch. But this year, amid the disruptions of distance and hybrid learning forced by the pandemic, the federal government opted to make meals free to all students, regardless of income. As many families stopped filling out the paperwork that would have qualified their students for free meals, schools saw their share of the compensatory funding dwindle.

In Grand Rapids, the district is losing out on about $500,000. South Washington County's allocation will drop by about $1 million — a full third of what it usually gets in compensatory funding. Roseville Area Schools will lose $800,000.

Multiple rounds of federal pandemic aid for schools have helped plug some budget holes, but school leaders say it has limited reach. The earliest round of funding was used primarily for all of the unexpected expenses that came with COVID-19: protective equipment for school staff, cleaning supplies, adding staff for things like contact tracing or coordinating the delivery of school lunches to homebound students.

Additional rounds of funding can be used to help fill in budget gaps, but some of that money is still held up at the state Legislature, waiting for final approval before schools get their share. And all of it has a limited reach; if districts use the one-time funding to hire a teacher or save a program from the cutting board, they worry how they'll pay for it the next year, or the year after.

"We are very appreciative of the one-time funding from the federal government, but one-time funding does not fix an ongoing structural deficit," said Shakopee Superintendent Mike Redmond.

School leaders said the complexity of school funding has made this year's dilemma difficult to explain to the public. With millions of dollars in federal aid flowing in, they know people might wonder why schools are seeking more money from the state, or contemplating asking voters for more local support.

That's also been a question at the Legislature, where Republicans and DFLers are divided on whether schools should get a boost next year on the per-pupil funding formula that forms the basis of all districts' budgets. The DFL-led House plan calls for a 2% increase, while the Republican-led Senate does not include an increase to the formula. DFL Gov. Tim Walz, meanwhile, proposed a 1% increase for next year.

A statewide survey earlier this year by several education groups found that 92% of districts expected they'd be facing a budget deficit if state lawmakers decided not to boost the main school funding formula.

There's also no consensus in the Legislature on other long-term school funding issues, like whether the state should chip in more to help districts cover mandated but unfunded special education costs.

Grose, the Grand Rapids superintendent, said he's hoping lawmakers will recognize that schools need help with new needs and longer-term budget issues that have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

"It's not like a tornado where you can infuse money and build new houses," he said. "The effects of this pandemic are going to be [here for] many, many years, and it's going to take school districts many, many years to overcome some of the challenges."

Erin Golden • 612-673-4790

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?