They were just flashes in full lives, but what flashes they were.

Ed Rogers kicking an extra point in 1903 to seal a tie between Minnesota and Michigan, leading to a chaotic scene of 20,000 fans storming the field and a Minnesota custodian finding a little brown jug the Wolverines had left behind.

Natalie Darwitz being informed that, at the impossible age of 15, she would be joining the United States Women's National Hockey Team as the youngest player in their history.

Toni Stone pulling on the uniform of the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues in 1953, becoming the first woman to play regularly in a major men's professional baseball league.

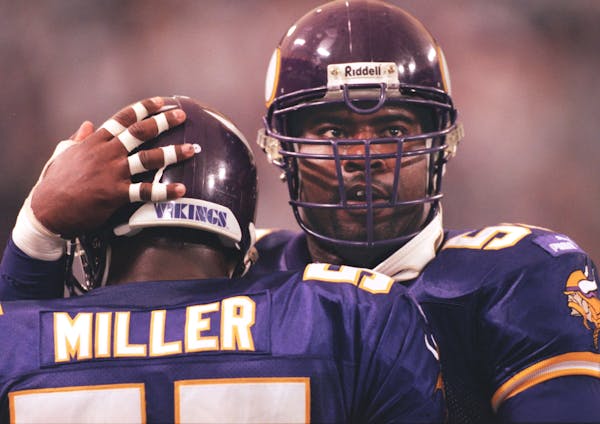

Chris Doleman arriving at the Metrodome in 1985 with his shirt buttoned to the collar, carrying a briefcase, going to work to destroy opposing offenses for the Vikings.

Kevin McHale, born on iron ore and the greatest basketball player the state has ever produced, holding his arms aloft, walking off the Boston Garden parquet floor as the Celtics finish 40-1 at home for the 1985-86 season.

Bob McDonald, standing in the hallway with his grandkids at Chisholm High School in 2017, getting ready to see the basketball court named after him following 53 years of record-breaking coaching for the Bluestreaks.

The achievements of these six changed the history of athletics in the state and around the country — and together, they make up the Minnesota Sports Hall of Fame Class of 2020. The Star Tribune, owners of the Hall of Fame, will induct these six in a pandemic-delayed virtual ceremony March 3.

The accomplishments in their sports were special. But what makes them pioneering figures in society is that their impact extended far outside the game.

"He wasn't the guy who was sitting around with a bunch of guys getting to know them. He led by example," former Vikings teammate John Randle recalled of Doleman, whose NFL Hall of Fame career included playing 10 seasons in Minnesota.

"I think for the Minnesota Vikings organization he came in and he touched so many guys' lives. He did something that I would say, that to me being a young guy, I was lucky to be around."

Darwitz was immediately drawn to the ice, saying it was an easy choice between tap dance with her mom and sister and playing hockey with her dad and brother.

Those early rink visits would lead the Eagan native to being the captain of the United States women's national team for four years, two NCAA titles with the Gophers and a spot in the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame.

But as Darwitz looked back at her playing career — she's now women's hockey coach at Hamline — she saw it as part of a lineage.

"I'm blessed that people before me paved the way for me to have those opportunities," she said.

"And hopefully I have done my part where I have paved a way for the players behind me to have more of an opportunity than I have had."

Maria Bartlow, the niece of Stone, said her aunt's unwavering passion to play baseball during her youth in St. Paul pushed her to create opportunities that were so gigantic, society took decades to recognize the impact.

"It wasn't until she got older and I went with her and she received one award and she just fell apart because she could not believe that it was so long, and she had to fight so hard to get her even pay or get half the pay that the men were getting," Bartlow said.

"Nobody was in her ballpark or in her field or anything like that."

Stone was born in Minnesota in 1921 and played every sport she could find growing up — hockey, football, golf, tennis, you name it — and by 16 she was playing semipro baseball. Stone died at age 75 in 1996 in California, and March 6 is "Toni Stone Day" in St. Paul.

Though McHale's legacy as a basketball player is unprecedented in the state — a three-time NBA champion, member of the NBA Hall of Fame and named one of the 50 greatest players of all time by the league in 1996 — he told the Star Tribune in 1992, as he neared retirement, that he knew he could find peace off the court through his ties to Minnesota.

"Hey, 99.9 percent of people don't play professional sports," he said at the time. "What do they do? They don't die. They get a job. I've got friends who are just as happy in their lives as I am in mine. I felt comfortable with my ability to do enough things that I could go back and make a life for myself in an area that I love."

While a lot of focus was given to McDonald's 1,012 victories with Chisholm, McGregor and Barnum, the most in state history, his son, Paul McDonald, said his dad's focus was always on a larger narrative as an educator.

"What he prided himself on was taking the average Joe or the No. 1 student in the class or the best football player and putting them all into one bowl and making sure that they knew no one was better than anybody else," Paul said.

"The dependability he showed, the caring he showed, and the support he showed not only to his own family but to his whole school family."

McDonald and Doleman both died in 2020; McDonald in October at 87 years old after contracting COVID-19, and Doleman at age 58 after a two-year bout with glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer.

Born in 1876 with the Ojibwe name Ay-ne-way-we-dung, Rogers became a civic and tribal leader after his Gophers playing days and went on to a historic law career.

Yet he was known as a humble man. When his granddaughter, Priscilla Herbison, was asked what he would have thought of this honor, she said what other inductees echoed: It was earned through a great deal of hard work.

"He was a humble man in the same definition of St. Augustine of what is humble, which is to be aware of and acknowledge the gifts and talent and wonders of life, and also to acknowledge your shortcomings, your limitations, without shame or regret," Herbison said. "That was my grandfather."

Humble people with extraordinary gifts and talents, open to the wonders of life, is an apt description for this incredible class of Minnesota sports legends.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

A Minnesota field guide to snow shovels: Which one's best?

Sign up for Star Tribune newsletters