KABETOGAMA, MINN.

W

es Johnson found the dying deer in the early morning as he was driving out to feed his cows.

Wolves had dug into its hindquarter, and it had deep stomach wounds, yet the deer still managed to leap the new fence that will soon wrap Johnson's entire property.

The fence was just 4 feet high where the deer had crossed onto the ranch — and had a 26-inch skirt that kept critters from digging under. The wolves attacking the deer never made it across.

After more than 15 years of trouble, Johnson may have finally found a way to keep wolves from eating his calves.

"They don't jump," he said. "They dig and they dig, but they don't know to back up that 26 inches. It's quite a deal."

Minnesotans in the Superior National Forest, in towns such as Grand Portage, Ely, Grand Marais and Kabetogama, live among some of the densest known wolf packs in the Western Hemisphere. For the last 20 years, the state's wolf population, roughly half of America's wolves outside Alaska, has remained near a stable peak — the highest number that available prey and human tolerance will allow.

Those who live among wolves know well the costs, dangers and rewards of keeping them around. They've developed ways to keep conflicts to a minimum and methods that may need to be adopted elsewhere if wolves continue their return to other parts of the United States.

Wolves are so often painted as enemies that it can be hard to see them for the shy creatures they are, said Kelly Applegate, natural resource commissioner for the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe.

Even in the woods of central Minnesota, where wolves are bountiful, they are hardly ever seen, and then often no more than as a flash of fur near the side of a road or as a moving shadow crossing a frozen lake, he said.

The Ojibwe have long said that their fate is tied up with the wolves, that they are not only brothers, but that what happens to one will happen to the other, Applegate said.

"Much like tribal people, they're so misunderstood," he said.

They mirror humans in many ways.

"They have leaders, and parents and a very organized family structure where each of the members has a role," Applegate said. "They truly are a reflection of man in the wild. That brothership is so close."

Some of that interdependence stems from the Ojibwe creation story, said Anton Treuer, professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University.

"There was this figure, half-human, half-spirit, who traveled around the earth with a wolf, naming everything," he said. "When they finished their job and everything was named, there was this prophecy that they would part ways and never live with one other again. But they would have parallel lives."

It's hard for Indigenous people not to see parallels with their own story, he said, being forced into boarding schools or prisons just as wolves were killed off and put into zoos.

"But there will be a resurgence," Treuer said the story concludes.

Lake Mille Lacs lies on the fringe of wolf range. The predators returned there over the last 20 years, spreading south from the northern woods. The Mille Lacs Band does not tag them or follow them, content just to know that they are there, listening, at times, to their howls and seeing their prints in the snow.

Conflicts do happen, but not as often as many would think.

From fences to trapping

Wolves generally prefer natural prey to livestock and can often live near ranches or farms for years before attacking cattle.

In Minnesota, wolves attack cattle at about 90 farms each year, according to the U.S. Agriculture Department (USDA). That's between 1 and 2% of all livestock operations in wolf range.

Over the last 10 years wolves annually killed an average of 70 calves, 10 adult cows, seven sheep and five dogs, according to federal officials.

Taxpayers pay ranchers market value for any loss that can be verified — an average sum of about $131,000 a year. Then, federal trappers kill the nearby wolves.

While wolves are a small problem overall, they can become big problems for individual ranchers when they home in on certain locations.

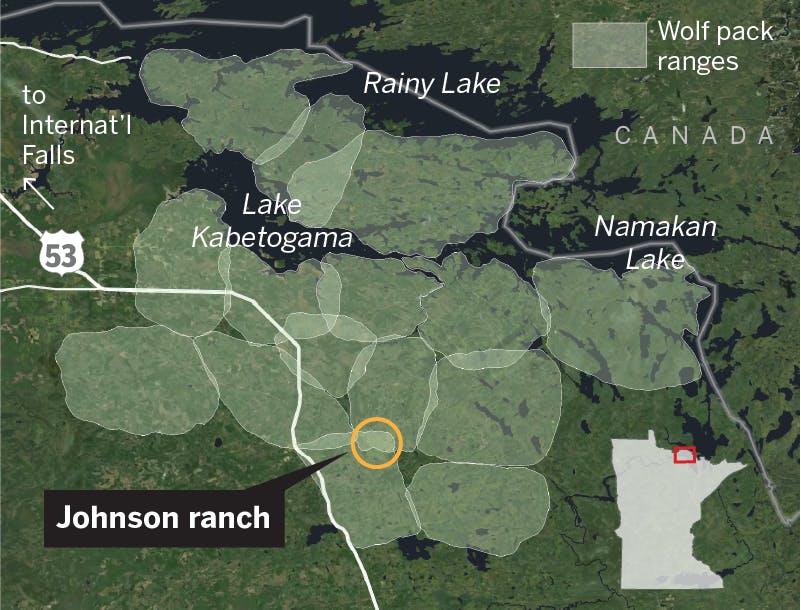

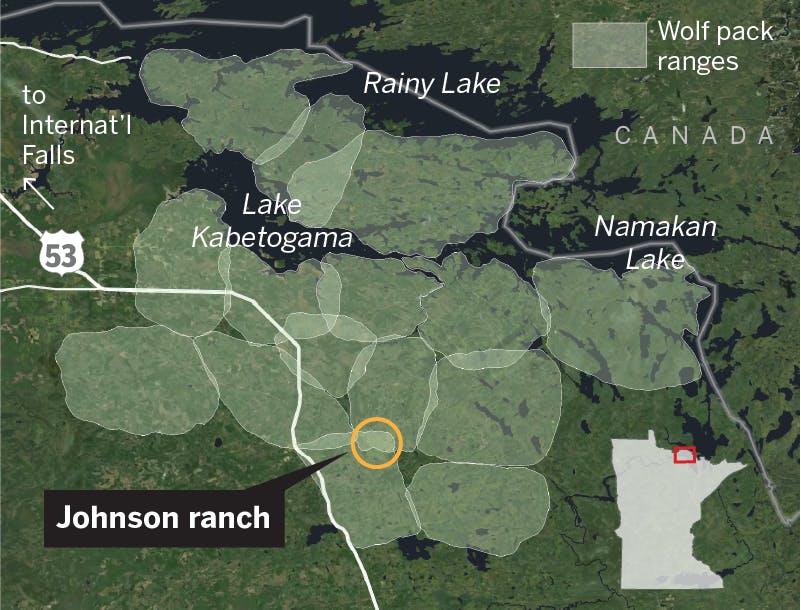

A ranch in wolf territory

A satellite map of Wes Johnson's ranch land south of Voyageurs National Park shows where it sits at the intersection of several wolf pack ranges.

Source: University of Minnesota, Voyageurs Wolf Project

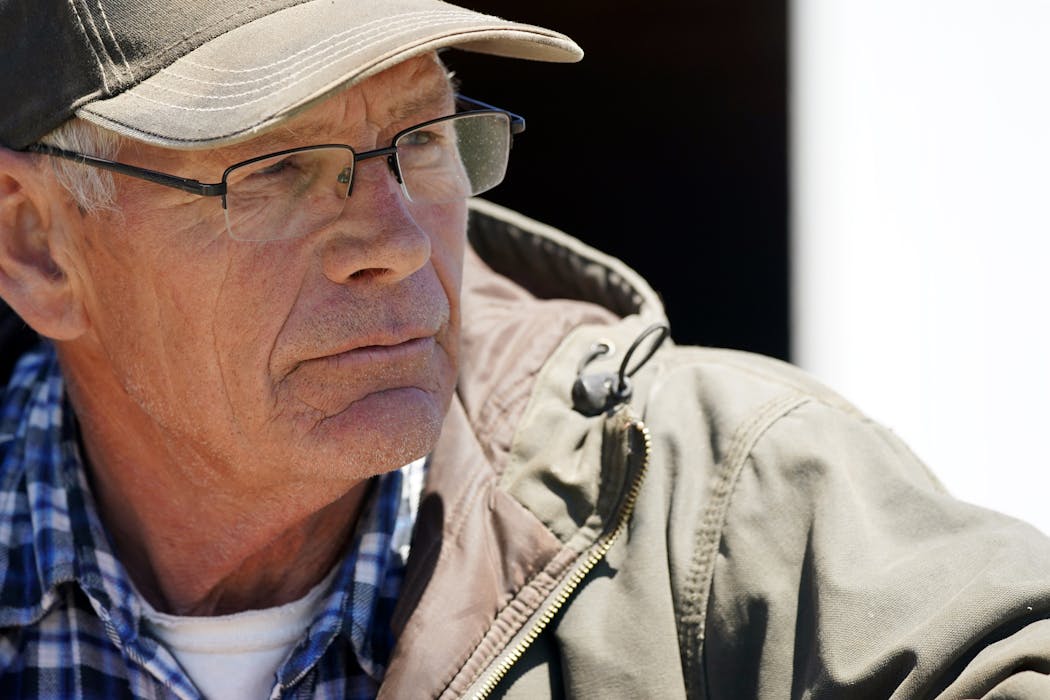

Johnson, who found the dying deer last winter, owns a 1,600-acre ranch just south of Voyageurs National Park.

He worked the ranch in his youth and bought it outright in 1993, expanding it by more than 1,100 acres.

"For the first 15 years, people would say, 'I can't believe you've had no trouble [with wolves],'" he said. "Then once they started, it's been nothing but trouble."

If there is a nonlethal way to keep wolves from attacking his 750 head of cattle, Johnson has tried it.

He uses flags and alarms. His granddaughter rides a horse around the property regularly because human scent has been known to scare them off. He even has guard donkeys, which will bray and charge a wolf on sight.

Still, every year wolves will kill calves on his ranch.

"It's not pretty," he said.

His granddaughter lost her dog, a little blue heeler. They heard a single loud yelp one night and then never heard, or saw, the dog again.

Sometimes cows get so worked up in the chaos when wolves attack that they break their legs. Sometimes the bones can be mended; most of the time they can't.

Johnson has put down many animals that the wolves didn't finish off.

After each attack, federal trappers come to bait, catch and kill whatever wolves happen to be in the area. USDA trappers kill about 200 wolves in Minnesota each year, twice as many wolves as live in all of Yellowstone National Park.

Things calm down for about six months, Johnson said, before the wolves attack again.

He knows where he lives — in a clearing in the heart of the oldest wolf range in the Lower 48.

"I have no feeling either way if they have a hunting season," Johnson said. "I wouldn't buy a license to shoot a wolf. I don't hate them, I just don't want them in my place."

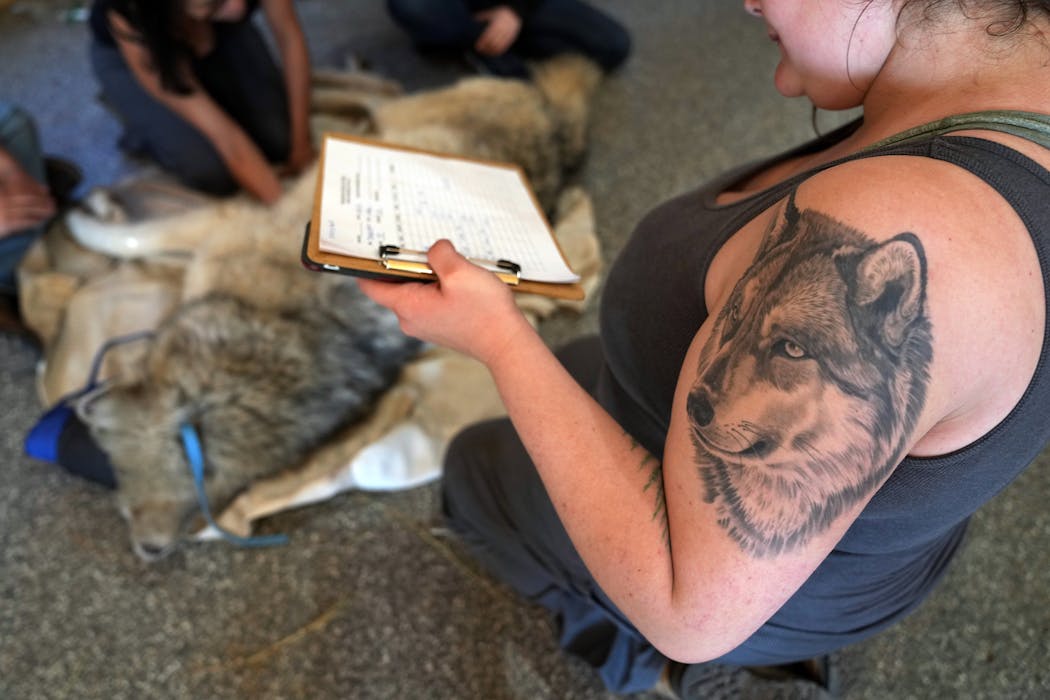

The cattle attacks are also a problem for Thomas Gable, leader of the Voyageurs Wolf Project, because the federal trappers kill some of the collared wolves researchers follow every year.

So the Wolf Project and Johnson set out to try something new.

They, along with the USDA, raised enough money — about $70,000 — to barricade the 7.5-mile perimeter of Johnson's land with a woven wire fence that ranges from 4 feet to 6 feet tall, plus a 26-inch skirt that keeps wolves from tunneling under.

Gable and Austin Homkes, another researcher, are installing most of the fence themselves. They hope to finish it this year.

Why that height? That's what was tested by Peggy Callahan at the Wildlife Science Center in Stacy, Minn. For whatever reason, wild wolves never seem to try to jump a fence of that height, only to dig under it.

Even when half-finished, the fence appeared to be working, Johnson said.

A collared wolf was among those that had wounded the deer and chased it to the ranch. The collar data showed the wolves tried to dig under the fence for nearly six hours, but were stopped by the underground skirt.

Eventually, they walked away.

"Once we get that fence up, it will be pretty rarely that we get a wolf in here," Johnson said, excitedly. "It's going to save a bunch of wolves for the people that like them."

International Wolf Center

The center in Ely, Minn., takes an up-close, matter-of-fact approach to wolves, hunting and conservation. Click to read more about each photo.

Shifting nature's balance

If wolves lose federal protections again, it will give the Minnesota DNR a chance to bend wolf management to the ecological and cultural priorities of citizens in different parts of the state.

For the Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe, for example, the fate of moose is a more immediate concern than that of the wolves north of Lake Superior near the Canadian border.

Logging and the urbanization of Minnesota over the last century, along with the shorter, milder winters of a changing climate, have boosted the deer numbers there to artificial highs, said Seth Moore, biologist for the tribe.

Brother Wolf

Native American tribes of the Great Lakes long considered the wolf a peer, a brother who hunted the same game and whose fate was intertwined with theirs.

Deer bring a brainworm parasite that spreads to moose and kills them. The high deer numbers also prop up an artificially high wolf population, Moore said, and the wolves eat moose calves.

If the state could tweak predator populations in the core moose range during the six key weeks of moose calf vulnerability, it's possible that the state's shrunken moose numbers could start crawling back, Moore said.

"Stable isn't good enough," he said. "Moose are a primary subsistence species for the band."

To bring wolves back under state control also comes with risk.

The state's management of wildlife has often been shortsighted, trying to out-manage things that naturally control themselves, Treuer said.

"It's like we want to kill off wolves so there are more deer for people to kill, and they keep managing it that way," he said.

But that's not the way the world works. Woodland caribou, a once common wolf prey, were hunted out of Minnesota shortly after European settlement. But before they died off, one of the state's last herds held on, for a time, on tribal land in Red Lake, Minn.

"It was not an accident that the place with the highest population of caribou also had one of the highest populations of wolves at the same time," he said. "Sometimes we just have to actually let Mother Nature manage things a little more."

In Ely, wolves are one more topic among many, from Donald Trump to mining, that divide the town.

Lori Schmidt, who has taken care of the captive wolves at Ely's International Wolf Center for more than 30 years, said it seems like people are losing a willingness to tolerate other opinions.

"You see it with the people who love wolves and hate hunters and with the people who are more consumptive of resources, who don't see the value of watching a wolf cross a snowy field," she said. "That's disheartening."

But there still are people willing to engage. The Wolf Center itself is proof of that.

The popular museum — neutral and matter-of-fact on questions such as hunting and trapping — was the brainchild of L. David Mech, one of the top wolf biologists in the world, because so many people wanted to travel with him as he studied wolves in northern Minnesota.

Bob Carlson, a lifelong hunter from Ely, believes the state should work to thin wolf numbers near towns and farms where depredations are a problem, while leaving wolves alone where deer populations are too high.

Carlson used to trap wolves in the 1960s, when the state offered bounties for them. He now traps beavers, which he sells to help feed the wolves at the Wolf Center.

"Wolves aren't much of a problem, with some exceptions," Carlson said. "If we could just bring some kind of control, especially around towns where people are having problems with their dogs and for some of these farmers."

Wolves attack dogs because they are triggered to defend their territory from competition of other canids. But they are so frightened of people that they pose little risk to human life.

There have been only two known wolf-caused fatalities in North America, one in Canada and the other in Alaska.

A wolf bit a teenager camping at Lake Winnibigoshish in north-central Minnesota in 2013. The boy was sleeping and kicked the wolf off him. It ran into the woods. The boy needed stitches, but the wounds were not life-threatening.

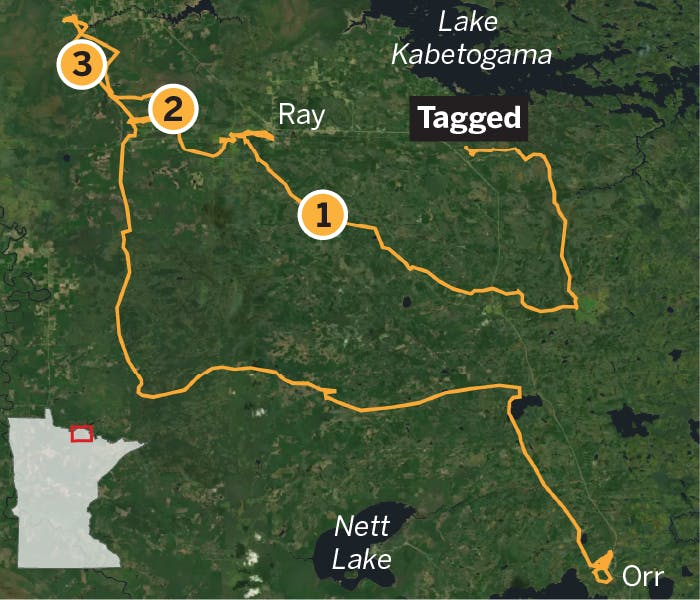

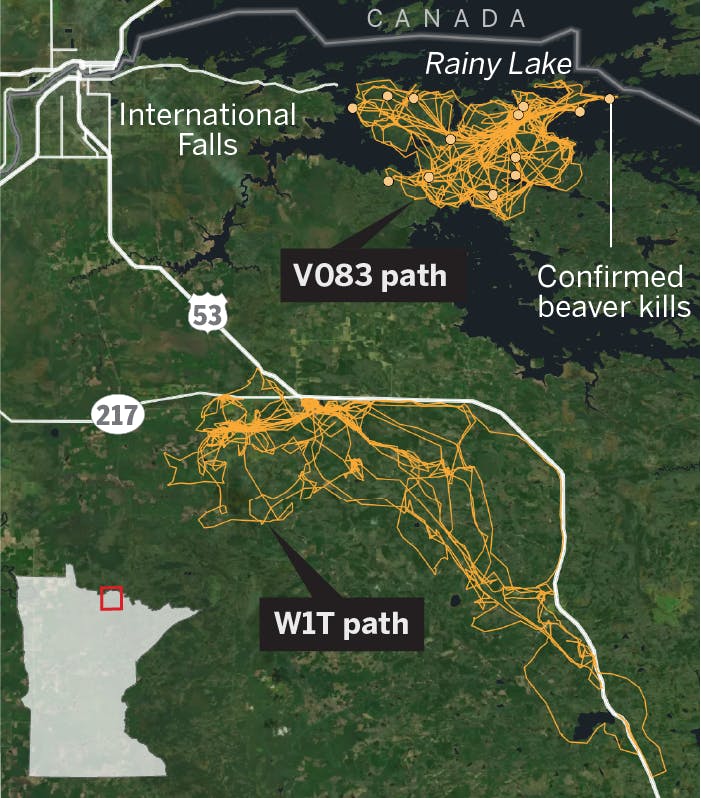

Roaming the North Woods

Steve Piragis of Ely lost a dog to wolves, and still regrets it, but he doesn't blame the wolves.

Piragis is an outfitter — owner of one of the last stops before the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness — and has an ear for mimicking wildlife.

On a hike one day, he heard yipping not far from a trail. He parroted the yip back and two wolf pups bounded up to him. He had stumbled onto a rendezvous site.

An adult wolf came, too, and looked him over, standing a few feet away. She turned tail and the pups followed her back into the birch and aspen.

Piragis knew wolves were in the area, but still let his dog, Sophie, outside for too long one day. He never found a trace of her.

"It was really our fault and it was really stupid," Piragis said.

He built a fence, and knows there is still a chance that Jack, his new young bearded collie that goes with him and his wife on hikes and ski trails, could also get attacked.

"You can't just live in a bubble," he said.

Few people who travel through his store every summer on the way to the Boundary Waters will ever see a wolf.

Source: Voyageurs Wolf Project

But they might hear them.

"They're a reason why there's a mystique about this place," he said. "You go to the Boundary Waters and disappear inside the wilderness, where mysteriously these wolves are not seen, but they've been since time immemorial.

"You can hear loons anywhere.

"But where are you going to hear a pack of wolves?"

![Regalia for a wolf dance made by Native American artists David L. Kline Sr. and Robert Kelly is on display at the International Wolf Center in Ely, Minn. The cape is made from wolf fur. Kline, also called Wolf Feather, described his inspiration for this piece: “The wolf to me symbolizes endurance ... the ability to go on no matter what's going on, just keep going. That's one reason I put it [wolf fur] behind my bells. They help me keep from getting tired when I dance.”](https://arc.stimg.co/startribunemedia/BG3CNDS4WQVQNFP4MARRBZQGQU.jpg?w=2500?fit=crop&auto=format,compress&cs=tinysrgb&dpr=2&crop=faces&w=525)