Busy bassist Billy Peterson showed up at Sound 80 studio in south Minneapolis like it was just another recording session. After all, producer David Zimmerman hired him all the time. But when he walked into the studio late that afternoon, he learned the surprise.

Bob Dylan, Zimmerman's famous brother, stood in the smoke-filled room wearing a black leather jacket and jeans. The Minnesota icon had recorded an album in New York, due to be released in three weeks, but he wasn't completely happy with the project.

So on Dec. 27, 1974, Peterson, along with a bunch of other local musicians in their early to mid-20s, were set to record with Dylan. Five of their songs ended up on the landmark "Blood on the Tracks," Dylan's bestselling studio album that landed in the Grammy Hall of Fame.

But the six Minnesota musicians never received official credit — until now.

Friday's release of "More Blood, More Tracks — the Bootleg Series Vol. 14" belatedly recognizes Peterson and the others because 500,000 jackets for the original album were already printed when the Minneapolis recording sessions took place.

"I know the music business with all the faux pas that go on," said Peterson, who has had a long career, including stints with the Steve Miller Band and Ben Sidran. "This is a rubber stamp of approval. It feels good. It's the most prestigious recording I've been on."

For acoustic guitarist Kevin Odegard, who has spent four decades campaigning for this recognition, the acknowledgment is not so much about "authentication and validation" but more importantly it made him feel like "a Musician with a capital M because my name is on that record."

Four of the "Minnesota Six," as they sometimes call themselves, got together last week to tape a cable TV program in northeast Minneapolis. The other two — guitarist Chris Weber from California and drummer Bill Berg from North Carolina — chimed in via technology.

Odegard, a singer-songwriter who was managed by Zimmerman at the time, was the only player who knew what the secret sessions were for. It was Odegard who contacted Weber, proprietor of Dinkytown's popular Podium music shop, looking for a certain kind of smaller acoustic guitar. That got the ball rolling.

Weber demonstrated an acoustic Martin guitar for Dylan at Sound 80. The Hibbing bard took a liking to Weber's guitar style and asked him to teach a song, "Idiot Wind," to the rest of the musicians.

Berg, who had played in jazz combos with Zimmerman in their native Hibbing, had his car packed for an impending move to Los Angeles to pursue his dream of becoming an animator for Disney. He stuck around, joining Peterson as the most experienced of the local players.

Dylan "was comfortable because he was with his homeboys," Odegard opined in an interview with the Star Tribune last week. "The sessions were relaxed."

Dylan had written a batch of songs earlier that year at his newly purchased farm near Buffalo, Minn. The project marked his return to Columbia Records after a so-so two-album detour to David Geffen's Asylum label.

First time in a studio

The Minnesota Six — who have played a series of live concerts in their home state over the years, starting in 2001 — have stories to tell.

Mandolinist/fiddler Peter Ostroushko, who was battling pneumonia, was summoned to the second session with Dylan, on Dec. 30, 1974. Not only was it his first recording project, it was his first time in a recording studio. He was 21 at the time. At one point, Dylan took the newcomer's mandolin to play it himself because the notes were too high for Ostroushko to handle.

The next morning the still-ill Ostroushko woke up and thought he'd dreamed about playing a recording session with Dylan. No, his buddy from the Podium told him. It really happened.

Odegard famously forgot whom he was talking to and suggested changing "Tangled Up in Blue" from a common folk-song key to one associated with rock 'n' roll shuffles. Dylan bought it, and "Tangled" became one of his most frequently performed tunes over the years.

Peterson said he never felt tense recording with Dylan.

"He doesn't go by the rules," the well-traveled bassist pointed out. "He has more of a jazz mentality. He loves the first take."

After the sessions, Peterson encountered Dylan in the Sound 80 parking lot. The superstar expressed his appreciation for the contributions of the Minnesota musicians.

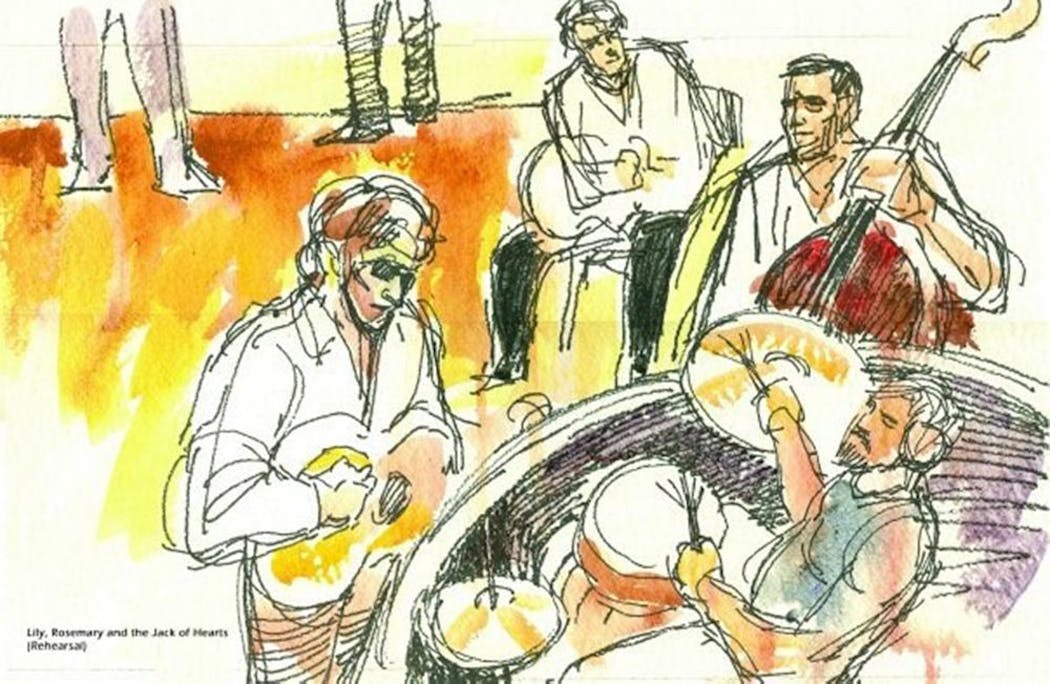

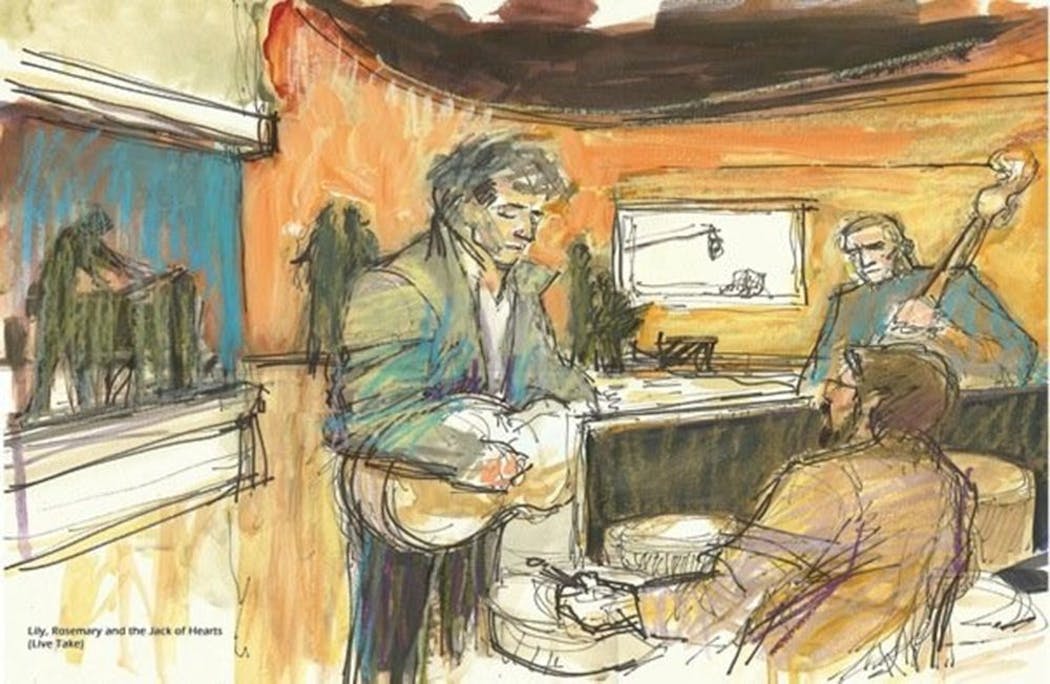

There were no photos of the recording sessions in Minneapolis or New York. The musicians remember two of Dylan's young sons hanging out at Sound 80. Drummer Berg crafted some drawings of the scene, depicting Dylan with sunglasses part of the time.

N.Y. vs. Minneapolis versions

The deluxe six-CD boxed set of "More Blood, More Tracks" features 87 tracks (plus handwritten lyrics and photos from the era), including many outtakes of the New York sessions in September 1974. These versions were often bootlegged, featuring more of a folk approach with just Dylan and a bass player. With a full band, the Minnesota readings feature an angrier, more forceful Dylan. For years, aficionados have debated which is better: the New York or Minneapolis takes.

The boxed set — and a single CD version that is available — offers remastered versions of the five Minneapolis songs, without all the effects that album producer Phil Ramone added to make the record more radio-friendly.

"They de-processed it," Peterson said of the new versions. "It cleans up everything and brings it right in front of your face. The reverb goes away. You can hear everything a lot better. It sounds like Bob's voice is in your ear. You can hear the spit."

There were a handful of Minneapolis outtakes for four of the five songs, but their whereabouts are a mystery.

In 2004, Odegard co-authored a book, "A Simple Twist of Fate: Bob Dylan and the Making of 'Blood on the Tracks,' " calling attention to the anonymous contributions of the Minneapolis musicians.

On Dylan's "Greatest Hits Volume 3" in 1994, there were acknowledgments for the Minnesota players on the hit song "Tangled Up in Blue" — but not totally accurate, recognizing guitarist Ken Odegard and bassist Bill Preston.

Odegard never gave up. As the de facto contractor for some of the musicians at Sound 80, he wanted to make sure that they got paid — $325 for each three-hour session — and received credit. The checks came quickly, the recognition did not.

Over the years, Odegard kept in touch with Dylan's managers and officials at Columbia Records. "I never, ever doubted that this day would come," he said. "I just didn't know when."

On "More Blood, More Tracks," there is no acknowledgment of Zimmerman's contributions as producer of half the album.

"David Zimmerman did everything right," said Odegard, pointing out that the younger brother never took credit in the family business. "He knew it would work because of that Midwestern ethic. It was trust. And it applied to Bob, too. The vibe was like being in a garage band in Hibbing."

Trust perhaps. On two cold December nights, these six Minnesota musicians found themselves in the right place at the right time accompanying the master on a masterpiece. As Dylan put it on one of the songs on the album, it was a simple twist of fate.

Twitter: @JonBream • 612-673-1719

The 5 best things our food writers ate this week

A Minnesota field guide to snow shovels: Which one's best?

Summer Camp Guide: Find your best ones here

Lowertown St. Paul losing another restaurant as Dark Horse announces closing