Was Moorhead once a destination for drunks?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Decades before Prohibition banned alcohol sales across the country, Minnesota's border with North Dakota was a booze battleground. And the center of this fight was Moorhead, which earned a reputation as a destination for drunks.

Chris Cope, who has roots in Minnesota and now lives in England, wanted to know whether Moorhead was truly once "a den of iniquity." A listener of the Curious Minnesota podcast, Cope asked the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project to look into the issue.

Cope attended Moorhead State University — now Minnesota State University Moorhead — in the 1990s. At the time, he heard local lore about how downtown Moorhead had once been the seedy side (or, depending how you look at it, the fun side) of the Fargo-Moorhead area.

"I was always struck by the idea of this, since the most exciting thing happening when I lived there was the annual spring opening of the Dairy Queen," Cope wrote in an email.

That old Moorhead lore Cope heard as a college student? It is spot on.

Moorhead's era as the region's hooch capital lasted from when North Dakota became a state in 1889 until 1915, when Minnesota inched toward Prohibition itself — ending Moorhead's racy and raucous era.

'A gunfight before and after breakfast'

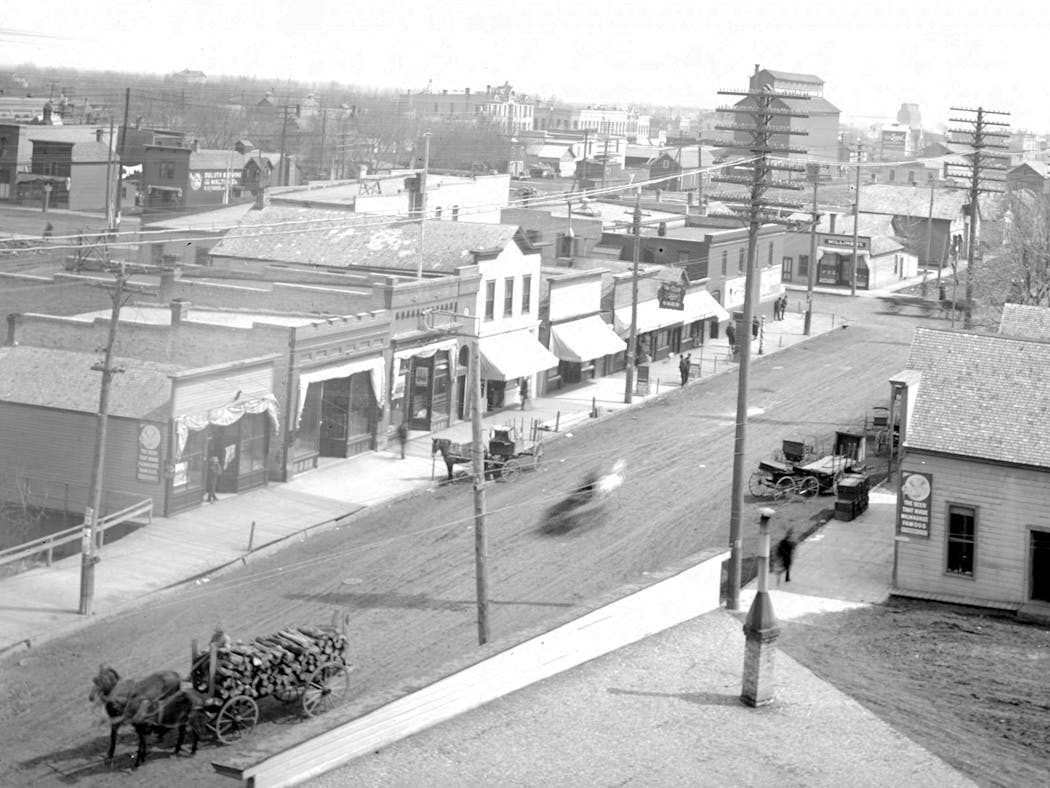

Moorhead's history of bawdiness stretches back even before North Dakota's statehood, when when it was a frontier town on the edge of Dakota Territory.

Moorhead was founded in 1871 when the Northern Pacific Railway came in and built a town. It was named for William Galloway Moorhead, an official for the railway.

"We were where the Wild West started in Minnesota," said Markus Krueger, programming director of the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County. "A gunfight before and after breakfast was not out of the normal in Moorhead."

By spring 1872, Moorhead was a town of 400 people. Residents included railroad laborers, saloon owners and sex workers, but no police officers, mayor, judges or teachers.

That initial era of anarchy didn't last long.

The last straw came the day after a late-night dispute in a gambling hall between "Slim Jim" Shumway and "Shang" Stanton in 1872. Stanton was grabbing a morning drink at a saloon when Shumway approached with two revolvers and shoved him. But Stanton was ready, whirling in his chair, shooting Shumway in the belly then fleeing. Shumway gave chase, firing wildly and killing a bystander — neighboring saloon owner J.P. Thompson — before succumbing to Stanton's bullet.

That very day, after a posse arrested Stanton, local residents formed the first Clay County government. They appointed a sheriff, a county attorney and a justice of the peace.

(Those who wanted the lawless culture fled Moorhead for Bismarck, N.D. After being pushed from Bismarck by the mid-1870s, they made their way to the place now most associated with the Wild West: Deadwood, S.D.)

Moorhead welcomes saloons

When the new state of North Dakota adopted a constitution outlawing liquor in 1889, Moorhead embraced the opportunity to become a regional capital of carousing. Early Moorhead leaders framed it as choosing prosperity over purity.

"Let the saloons come," Moorhead Mayor John Erickson, a brewer, said in 1888, according to MNopedia, an online encyclopedia developed by the Minnesota Historical Society. "The more the better it will be for us. They pay more in taxes than anyone else. How many temperance people … pay $500 a year in taxes?"

The Red River marked the boundary between wet and dry, between teetotalers and tipplers. By selling booze to North Dakotans who crossed one of the two bridges linking the city to Fargo, Moorhead became prosperous. Free taxis, or "jag wagons," took people from Fargo hotels to Moorhead drinking establishments like John Haas' Midway, the Three Orphans Saloon, the House of Lords and the Rathskeller on the Rhine — with its polka band and arcaded porch.

"They ran the gamut, from these really luxurious pleasure halls with bands and electric lights to seedy little dives," said Bill Convery, director of research at the Minnesota Historical Society. "There were rows and rows of these saloons. You walked across the bridge and you were in what was known as Hamm's Row, these saloons owned by Hamm's Brewery."

Moorhead became a boozehound's paradise. Moorhead had 47 saloons and a brewery in 1900, with only 3,732 residents. Alcohol was the city's top economic driver.

North Dakotans couldn't transport liquor back over state lines. But a loophole allowed them to order alcohol by mail. As long as the money changed hands in Moorhead, your crate of whiskey could legally be delivered to your door. One in 10 families in Moorhead were in some way supported by the liquor business, Convery said.

But the liquor business brought other unsavory things.

Moorhead's red-light district was an especially vibrant one. Liquor distributors smuggled their wares onto nearby Ojibwe reservations, where liquor was illegal. And Moorhead law enforcement was particularly busy. Moorhead police made three times as many arrests around the turn of the century as police in Fargo, a city three times Moorhead's size. And the majority were alcohol related.

"Moorhead got the bad reputation. But if you did a census of everyone in Moorhead saloons in 1900, most of them would be North Dakotans," Krueger said. "It wasn't just Fargoans crossing the river. It was people from all across eastern North Dakota. We got the reputation of being the Las Vegas of getting drunk in the region."

The party ends (legally, at least)

The party ended on June 30, 1915. The Minnesota Legislature had just changed state law removing exemptions for local municipalities if a county voted to go dry. With Moorhead known as a town for inebriates, Clay County voted to go dry. The vote was a landslide.

Before the law went into effect on July 1, Moorhead held a street party. Eight thousand people attended and reveled in the fireworks. Some bars ran through their liquor supply, while others literally turned back their clocks so midnight and sobriety would get pushed back a little further, Convery said.

Then Moorhead went dry — at least officially. "Blind pigs," or illegal saloons, operated in semi-secret and continued after Prohibition barred alcohol across the country in 1920.

But Moorhead struggled. With the saloon era over, the city became an agricultural community. Plummeting wheat prices after World War I hit Moorhead especially hard.

Krueger mused that Fargo-Moorhead's reputation as a hard-drinking town — it's often at the top of the list of the drunkest metropolitan areas in America — isn't just because of the many colleges there. It's also because of the area's distinct drinking history, he said.

(Readers interested in learning more can attend Krueger's popular monthly local history talks — at Moorhead's Junkyard Brewing Company, of course.)

He also knows one community being governed by two states' laws makes for unique tales. When Sunday liquor sales were illegal in Minnesota, Moorhead residents just headed over to Fargo. With recreational marijuana now legal in Minnesota, Fargo residents can grab their green in Moorhead.

"We're in many ways one community, but we're in two different states," Krueger said. "And those two states are so often opposite of each other — then and now, too."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

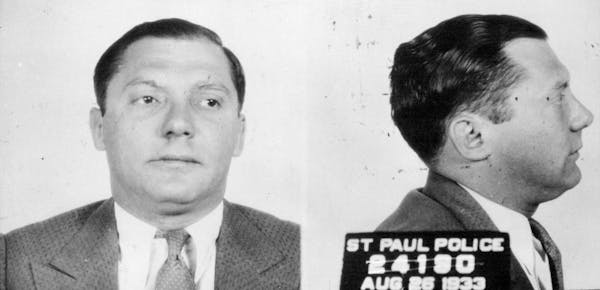

Did St. Paul really protect gangsters during the Prohibition era?

Why is St. Paul located where it is? Hint: It involves liquor

Why does Minnesota have municipal liquor stores?

How did Minnesota get its shape on the map?

What was the first movie filmed in Minnesota?

How did Stillwater become home to Minnesota's first prison?