An overwhelming majority of likely Minneapolis voters say crime is on the rise, a view strongly held by residents of every race, gender and age group across the city, according to a new Minnesota Poll.

Nearly 75% of voters say crime has increased, 25% say it is the same and 2% aren't sure. Not a single person surveyed said they thought crime in Minneapolis has lessened in the past few years.

Julie Anderson, who lives in the Cedar-Isles-Dean neighborhood, said she is so worried about rising gun violence, carjackings and other crime in the area that she is sometimes too afraid to go for walks or bike rides around the city.

"We have a big problem to clean up right now," said Anderson, 68. "We need help."

The Star Tribune, MPR News, KARE 11 and FRONTLINE sponsored the poll, which was conducted Sept. 9-13.

Crime and policing issues dominate the city's fall election campaigns. Minneapolis voters will choose a mayor and the entire City Council, and decide whether to replace the city's 154-year-old police department with an as-yet-undefined department of public safety.

That proposed charter amendment would remove a provision requiring a minimum number of police officers, freeing city officials to reduce the size of the force. It will be the first election in Minneapolis since the police killing of George Floyd in May 2020, which ignited a nationwide debate over race and policing.

The election also is unfolding amid a dramatic spike in crime across the city. A Star Tribune analysis this summer of crime data found that gun violence and homicides have surged in Minneapolis, putting the city on pace for its most violent year in a generation. There have been 71 homicides this year, compared with 60 at this time last year. Minneapolis Police Department statistics show that property crimes have declined, while violent crimes, such as robbery and aggravated assault, are up slightly.

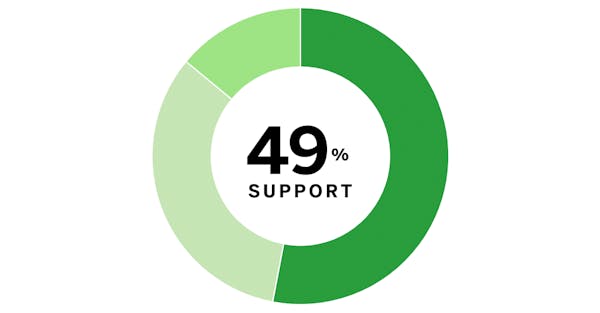

The poll found that 55% of voters say shrinking the police force would lead to negative consequences, while only 20% think a reduction would positively affect public safety. The rest of voters polled were either unsure or said they think a reduction in police would have no effect.

White voters were the most likely to say a smaller police force would lead to positive outcomes. Among Black voters, only 13% say reducing the number of police would be beneficial compared with 21% of white voters.

Roble Yonis, 39, who lives in the Seward neighborhood, said local residents recently experienced a rise in crimes against the area's mosque, and worshipers are sometimes robbed on their way to morning prayer.

He said the Police Department needs more officers of color.

Yonis, who is Black and of the Oromo Ethiopian ethnic group, said police must know the specific needs of the community in order to address crime in the Seward neighborhood. For instance, he noticed that when Somali police were present, both the officers and residents of East African decent operated from a place of mutual understanding.

Yonis said he has not seen Somali officers in the neighborhood since Floyd's death. As a result, he said, crime that hasn't been seen for years in Seward neighborhood has re-emerged.

Mason-Dixon Polling & Strategy Inc. of Jacksonville, Fla., surveyed by phone 800 registered Minneapolis voters who indicated they were likely to vote in November.

The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3.5 percentage points. The poll surveyed an additional 343 Black voters in Minneapolis who indicated they are likely to vote, for a total of 500 interviews. This "oversample" allows for a more direct comparison of the responses of white and Black voters, with similar margins of sampling error.

Younger voters were more likely to support reducing the size of the police force. Even so, half of voters younger than 50 say city leaders should reject proposals to cut the size of the police force. Among those older than 50, 60% oppose reducing the force.

Derek Loftis is among those who say the city is better served with fewer police officers.

Loftis, who is white and lives in northeast, said he does not experience the crimes plaguing other parts of the city.

"The police have too much responsibility," said Loftis, 31. If those responsibilities were divided among several organizations, it would inevitably result in fewer police officers, he said. "They're not the catchall."

Anderson, the Cedar-Isles-Dean resident, has a different view. The retired Minneapolis public school teacher said she wants a well-trained, larger police force that has the time to become a part of the community, much like the police who worked in the school system where she taught.

"We need police to be beat cops, where they get to know the people in their community in the neighborhood," she said.

During the unrest after Floyd's murder, when dozens of her Longfellow neighborhood's businesses and local restaurants were damaged or burned down, Meghan Harney, 41, called 911 three days in a row — and got no answer.

"No one would come," said Harney, a white physician and longtime resident. "That fear that I felt for just a couple of days gave me a little bit of a glimpse in how some people feel their entire life in certain parts of the city."

This story is part of a collaboration with FRONTLINE, the PBS series, through its Local Journalism Initiative, which is funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Staff writers Libor Jany and Kelly Smith contributed to this report.

Christina Saint Louis • 612-673-4668

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?