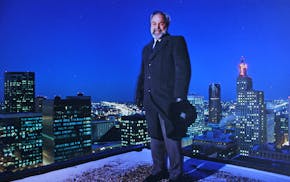

In September 1995, Mark Koscielski walked into a hearing over his Minneapolis gun shop wearing a T-shirt that had a drawing of the Grim Reaper stalking the city skyline.

"Murderapolis," the T-shirt read. "City of Wakes."

It was the first time the term appeared in this newspaper, but it would be repeated in countless political ads and featured in the New York Times. Since then, when homicides peaked at 97 bodies, Koscielski has sold 4,000 to 5,000 shirts.

While 2009 was still a pretty good year for gun sales and safety classes, it was a lousy one for T-shirts. Nobody could be happier than Koscielski, who prints them only when the murder rate hits 50.

Asked if he would prefer to never sell another shirt, Koscielski said: "It goes without saying."

Last year there were 19 murders in Minneapolis, an ebb that hadn't been seen since the 1960s and half the number of 2008. Koscielski gives partial credit to Police Chief Tim Dolan -- "finally, a chief who can deal with people and deal with crime."

But others say it's tough to give credit, or place blame, unless politics are involved.

In the mid-1990s, the murder rate became a dominant campaign theme as candidates blamed one another for the problem. Republicans took out ads saying Democrats were "soft on crime," and Democrats blamed cuts to social programs or boasted about "Clinton cops."

Now that the murder rate has plummeted, you might want to get out of the way if you see politicians gathering, because they are almost certain to stampede to take credit for it.

"Isn't that the way?" deadpanned Brad Johnson, who was head of the homicide unit just as murder rates surged.

Johnson, now inspector for Minneapolis Park Police, shudders when he thinks of the days when the morgue was filled with bodies and murder interrogations were a nightly ritual.

"It was crazy," he said. "In the '90s, there were a rash of 'whodunits,' including a lot of high-profile murders and a couple of serial killers." Johnson said the crack epidemic and the emerging turf battles between highly organized gangs contributed to the mayhem.

But when asked to explain the drop, Johnson and others are less certain. "It's hard to put a finger on one thing," he said. "Part of it is cyclical."

Criminals from those times are either dead or in prison. Several large families that were involved in homicides have literally died off. Gangs have become smaller or dispersed to suburbs and small towns. Johnson also said CODEFOR, a way to map crimes and coordinate across precincts, helped.

Mark Ellenberg was in charge of homicide during the record year and believes that police procedures can affect crime statistics, but politicians cannot.

"But [police] don't have as big a role as social factors like economics and demographics, having fewer young men in the population," he said. "You can put up a sea wall, but the sea itself is going to have the biggest say in where it goes."

Homicide detectives from that era recall hundreds of hours of overtime, days without sleep and an increasingly callous attitude toward death. When gang members shot each other in retaliation, some officers were so fed up with the violence they dubbed the cases "damage to occupied clothing," recalled one former detective.

If they didn't nail the case in two days, it would likely go on the back burner for a "fresh one." Weekends were pandemonium and detectives sometimes struggled to keep witnesses and victims straight -- and themselves sober enough to work even if off duty. Few politicians had solutions.

"For any politician or administrator to take credit, or get blame, would be ludicrous," said Jim DeConcini, a homicide detective at the time. "It's a societal problem; we just mopped up."

Still, now that there is relative peace, expect the back-patting to begin.

"When murders go down, everybody says it's because of their program," said one former detective. "Will they take the blame when murders go up? Nope."

I dug out a couple of quotes from former Republican Chairman Chris Georgacas, now a lobbyist, slamming liberals for all the crime. I asked if he was prepared to now credit those in power, such as Mayor R.T. Rybak, for the decline. His response:

"In my misspent youth as a political party leader, I leveled pretty incendiary -- and sometimes misplaced -- charges against the late Paul Wellstone and other DFLers for the spike in violent crime in the mid-1990s. But truly, only a small amount of blame or credit can be assigned directly to politicians for crime rates in a given area."

Candidates, are you listening?

jtevlin@startribune.com • 612-673-1702

Depressed after his wife's death, this Minneapolis man turned to ketamine therapy for help

Tevlin: 'Against all odds, I survived a career in journalism'