Nancy Uden took her place in front of legislators, the first to testify inside the overflowing hearing room near the Minnesota Capitol. A head wrap covered her scalp. It hid 36 electrodes that slow cancer cells' growth, perhaps adding months, even years, to the time she has left.

"I'm not afraid of death, but I am afraid of how I will die," she told lawmakers and onlookers. For more than a year, Uden has battled glioblastoma, a devastating form of brain cancer with an average survival rate of 14 to 16 months. She was beating the odds, but she knew that could change in an instant: "I don't have time for long debates. This bill has been in front of the Minnesota Legislature for 10 years already. It's time to act."

The bill — supporters call it medical aid in dying, opponents call it assisted suicide — would allow physicians to dispense life-ending medication to terminally ill adults with a prognosis of less than six months to live. Patients would then ingest it themselves.

Leading into this legislative session, supporters were optimistic. Similar bills had gone nowhere in previous years, but they liked their odds with this DFL-controlled government. The issue jumbles predictable political alliances: Supporters frame it as bodily autonomy or as a bulwark against government intrusion; opponents frame it around the sanctity of life or fears that a slippery slope could force suicide on people with profound disabilities.

Uden, 72, understands the irony of spending what may be her final cogent months advocating for a law that could help her die.

Nancy Uden is fighting for her life while she fights for a choice in her death.

Nancy Uden is spending what may be the end of her life advocating for a peaceful death. She and husband Jim went to the State Capitol early this year and she testified before a House panel on medical aid-in-dying legislation. Her daughter Brittany Edwards holds back tears as she rides an elevator with her mother on that January day.

She is determined to live her remaining days fully. She hopes to travel to Sweden and Arizona. She wants to see the pop star Pink again. She yearns to meet her first great-grandchild, due in May.

She's had aggressive treatment: surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. In the year after diagnosis, her doctor at Mayo Clinic in Rochester relayed little but good news. But the median time to recurrence is less than 10 months. Uden is already a few months past that.

When the cancer returns, she worries a growing tumor could press against her brain, inducing seizures and hallucinations, bringing painful headaches and blindness, stripping away her communication and tinting her skin blue. It's the type of death she doesn't want loved ones to witness.

She told legislators of the seizure that caused a car crash in late 2022, of waking up at North Memorial Health Hospital, of doctors finding a brain mass.

"I promised my family I would fight this ugly disease until there's no hope left," she told the committee. "If there are no more treatment options, I deserve more death options."

Uden wants to die like her mother did: Surrounded by family, a serene look on her face.

"It is now very real and urgent to me," Uden told the committee. "The Minnesota Legislature has made bodily autonomy a priority. Well, this is the final act of autonomy that any of us will ever have."

The living room blinds were pulled down at Uden's house in Corcoron, keeping the afternoon sun from triggering her recently diagnosed epilepsy. Uden sat with her poodle mix, Ava, and talked about dying.

Nancy Uden washes her scalp before shaving it so that her husband, Jim, can attach adhesive transducer arrays to her head, part of her treatment for glioblastoma, a devastating form of brain cancer.

"If I die of glioblastoma, it'll be ugly," Uden said. "It's going to affect my brain. I could lose my ability to control my bowels, my bladder, being able to walk and talk and have my memory. If it gets to the end and it's this horrible, ugly thing, I want a different option."

Uden knows this topic stirs unease. When she spoke in the packed legislative hearing room, she was surrounded by tales of personal tragedy. A woman with leukemia guessed she'd die before this hoped-for legislation passes. A woman paralyzed in a car crash in the 1980s was grateful that assisted suicide wasn't an option after her accident. A medical ethicist testified of no instances of coercion in the 10 states and Washington, D.C., where this is legal. Dozens testified about their own terminal illnesses or loved ones with painful, drawn-out deaths. Some physicians opposed, some supported. Religious conservatives spoke of the morality of intentionally ending life and their fears that this narrowly defined law would be expanded.

One physician compared this to people who jumped from the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. Would anyone call that suicide, since death was imminent and they simply chose a quicker, more painless way?

Uden understands that unease. She also believes no one should have a say in her death other than her and her family. Her biggest concern with dying of glioblastoma isn't her own pain.

"I don't want my kids' last memories of me to be hallucinations and having seizures," said Uden, who retired a few years ago as a Great Clips executive.

"This will be harder on us than it'll be on you," replied her husband, Jim, a retired pastor.

"I want them to experience me at my best," she said. "That's all we have when someone's gone: Memories. And so I want those memories to be good. They won't all be good. But to the point I can control those memories, I want to."

Months before her diagnosis, the Udens moved into a new home in the northwest suburbs, ready for life's new chapter. With her relentless drive, Uden had overcome much: a childhood in an alcoholic home, a couple of failed marriages, poverty as she raised three daughters while working and attending school, her own battle with alcoholism. As they grew older, Uden's daughters admired their mom's tenaciousness, her ability to fix any problem. She's the type of person who has nicknamed her brain tumor: "Gil," short for glioblastoma. Her daughters call her President Mom.

With her family gathered for Thanksgiving, Nancy Uden looks out over the table with love and pride at her home in Corcoran.

Then came the problem no one could fix.

"You assume your parents will die before you, but you assume they'll die of old age," said Wendy Parsons, Uden's oldest. "You don't ever think ... the matriarch, the glue that holds the family together, will die in the near future of something really horrible."

This topic brings back vicious memories for Parsons. A few years ago, her father, Uden's first husband, was diabetic and depressed, paranoid and alone. He got drunk, went to his basement and shot himself. This bill, Parsons believes, isn't that. This is planned, thought-out, peaceful.

The rest of Uden's family feels the same way.

"She's created this good life," said her middle daughter, Amy Gray. "She deserves a good death."

"The government shouldn't get in the way of us making the choices families feel are best for their lives," said her youngest daughter, Brittany Edwards. "If you don't agree with it, then don't do it."

Nancy Uden hugs her youngest daughter, Brittany Edwards, at Thanksgiving. Her oldest daughter, Wendy Parsons, said: "You assume your parents will die before you, but you assume they'll die of old age. You don't ever think ... the matriarch, the glue that holds the family together, will die in the near future of something really horrible."

As she went through chemotherapy, Uden thought a lot about death. She told her family she wants a living funeral, where friends could say goodbyes, the things we should hear before passing away. She wants to be cremated, her ashes spread on Lake Tahoe and in Montana.

But she's also kept hope. She aspires to set the record for glioblastoma survival. (The longest anyone has lived after diagnosis is two decades.) She's taken every measure to help with cancer: switching depression medication to Prozac, which research indicates may help fight glioblastoma, and going to vision therapy to retrain her brain and eyes to work together, and reading books on positive thinking. Her terminal disease gave her perspective. This had become, against all odds, the best time of her life.

And somehow, news from doctors kept coming back good.

In a Zoom appointment in the fall, her neuro-oncologist interpreted her MRI and bloodwork: "Good news all around," he said. In December, days before Christmas, her husband drove her to Rochester for another appointment: More good news. Uden felt like dancing.

On the way home, they hit rush hour on Interstate 494. Uden was exhausted. White headlights sped toward her. Red brake lights flashed. Her husband thought she'd fallen asleep.

"A perfect storm," Uden recalled later.

In the passenger seat, Uden had a cluster of seizures, one after another. Her husband called their granddaughter, asking her to call an ambulance to their house.

She spent four excruciating days at Methodist Hospital, heading home on Christmas Eve. It felt like a trial run for the death she wanted to avoid. She told doctors she was going blind. She hallucinated. She screamed she was dying: "Get the crash cart in here!"

"They were seeing the ugliest parts of what I worry my death is going to look like," Uden said. "You could say, 'Well, now they're ready for it.' No! That's something I never wanted my kids to have to see. The difference next time is I don't come back."

Last month, Uden's husband again drove her to Mayo: Bloodwork, an MRI, physical therapy. That afternoon, her doctor reviewed the results. He didn't have good news. The cancer had returned.

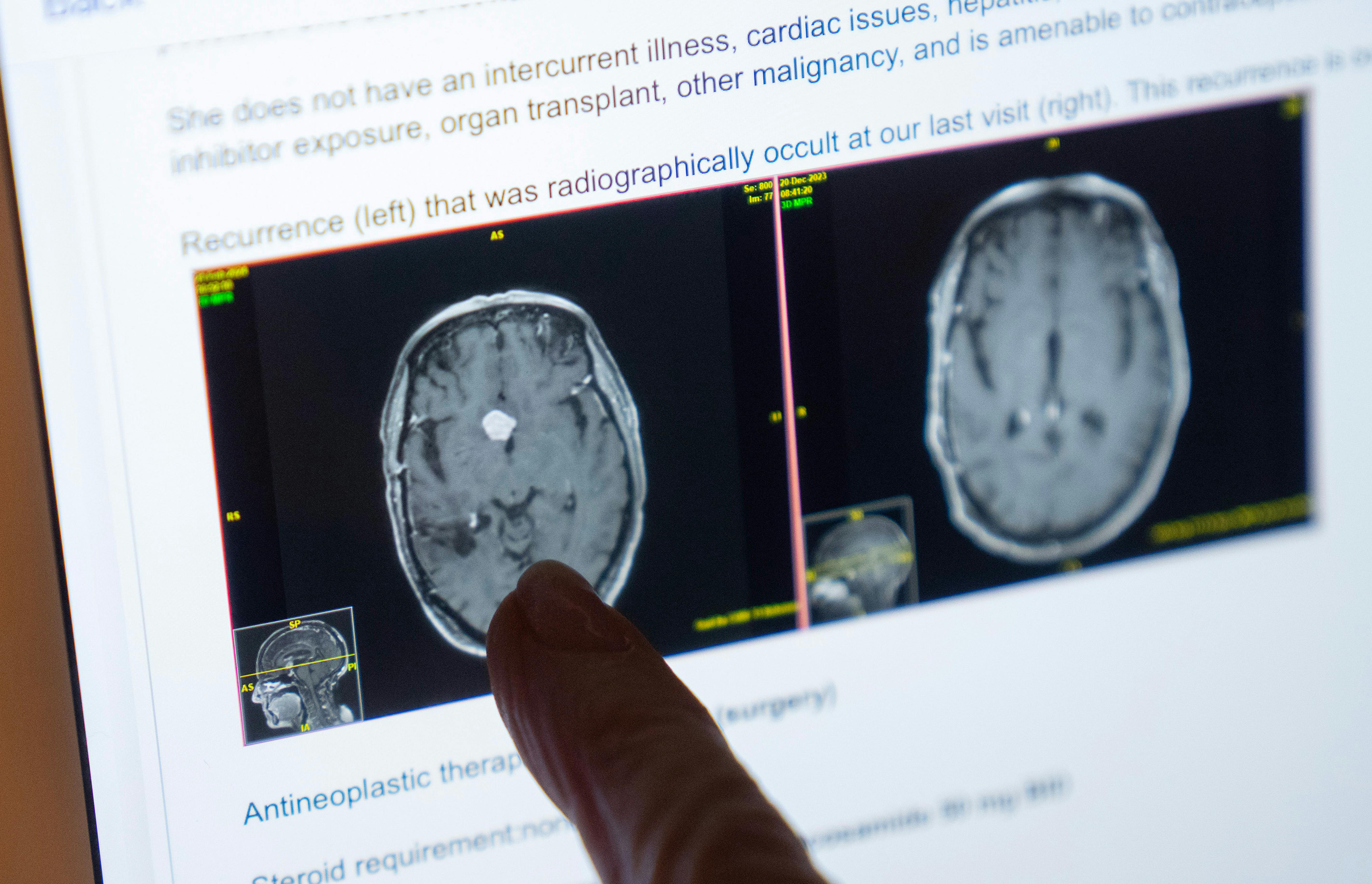

The Udens arrive for a day of medical appointments, and the news from doctors isn't good: Nancy points to a new tumor growth on her most recent MRI brain scan.

The new tumor was smaller than the first and in a different spot: the middle of her brain, roughly between her eyes. Her husband, Jim, cried: "I can't imagine my life without you," he told her. There was a silver lining. It wasn't a regrowth of the previous tumor, her doctor said, meaning the treatment worked. True to form, Uden didn't cry. She talked it out with her therapist the next day. She worried how another surgery could affect her.

Meanwhile, she continues to advocate for legislation she hopes will get passed before her cancer propels her toward an ugly death. She reminded herself that this battle is about more than her; it's about this option being available for others in the future. But the Senate majority leader has indicated a bill is unlikely to pass this session.

"I know there are Minnesotans who are ready," State Sen. Erin Murphy said. "It's going to take time for us as a people, as Minnesotans, to reconcile the way we feel and what we think."

Opponents find this bill both dangerous and unnecessary. Cathy Blaeser, the co-executive director of Minnesota Citizens Concerned for Life, would rather the Legislature focus on better palliative care, hospice care and mental health care.

"We don't make good law when we make law based on hard stories," Blaeser said. "It's hard to say, 'No, you have to suffer, you have to go through that.' That's callous. But it's dangerous for the rest of society — when the solution for hard problems is death, that slippery slope creates a culture where if there's a problem, it looks at what's the quickest way."

Uden vowed to fight for this medical aid in dying bill the rest of her life.

"I can't imagine my life without you," Jim Uden tells his wife. He tucks her in for bed most nights.

"If this bill doesn't pass — and if I don't pass — I feel sorry for the people that have to deal with me next year," Uden said. "This time, I'm coming at it like, 'Nice guys win.' Next time I'll come at it with so much anger and ferocity."

Mayo doctors are getting her into a clinical trial for immunotherapy starting this week. Surgery to remove the newest tumor is scheduled for March 19. Three days later is a big deadline: If the bill isn't heard by a Senate committee before then, it likely won't reach the floor for a vote.