Opinion editor's note: Strib Voices publishes a mix of guest commentaries online and in print each day. To contribute, click here.

•••

I'm the current president of the Minneapolis Board of Estimate and Taxation, the body that sets the annual limit on property tax increases under which the mayor and City Council must devise a budget and adopt a levy.

Last August, I made the case here for diversifying the city's sources of revenue ("Minneapolis ought to diversity its income," Aug. 12, 2024). Since then I supported the mayor's proposed levy for 2025, despite the onerous consequences for homeowners, because he and City Council President Elliott Payne pledged to undertake serious study of the feasibility of alternative taxes.

That examination is in its early stages. The case for diversifying revenue is that our regressive property tax has become the shock absorber for annual increases in the city budget, creating hardship for many senior and other low-income homeowners. This is compounded by more of the levy's burden falling on homeowners over the past several years. That's because home values have remained stable while apartment and downtown commercial values fall. The latter isn't likely to rebound for years.

Many people have responded to this situation by suggesting that the city cut its budget. I believe there's merit in a study commission — either internal or outsiders or both — to examine factors influencing growth in the city budget. I stand ready to serve or assist. St. Paul's fiscal situation recently underwent an outsider examination.

Nevertheless, Minneapolis needs to diversify its income. My early favorite for adding non-property tax revenue is a selective city income tax. My concept is for a modest 1% tax which would be paid only by households with incomes of at least $200,000 annually, or about two and a half times the city's median household income. The numbers are negotiable. There are something in excess of 24,000 such households in the city. My rough calculation is that such a tax would yield at least $40 million annually. This should be shared by the city and the Park and Recreation Board. My initial hope was that this added money could supplant the property tax to cover budget increases; recent events may require it to offset Trump administration-induced federal and state aid cuts to the city that could hit $70 million.

The income approach has several advantages. One is that an income tax, in comparison to a wealth or payroll tax, is administratively simple. It could be levied as an add-on within the state income tax form. No new, complicated process would be needed to figure a taxpayer's assets, as with another possibility — a wealth tax.

Another advantage is that some 5,000 local jurisdictions across the nation already charge a local income tax, in both red states and blue. There's plenty from their experiences to guide us.

Additionally, part of a local income tax could be deductible for those who itemize deductions on their federal taxes.

Further study would help us to determine whether there's a fatal flaw in a local income tax for Minneapolis. For example, some homeowners have told one council member in my area that they'd move if a such a tax was imposed. The experience of other cities should tell us whether that's likely to be the case, how significant a factor that is and whether those departing are replaced by other move-up taxpayers.

If there's a fatal flaw, there's an alternative approach possible. That's a more steeply graduated property tax. Right now, any home value over $500,000 is converted to its taxable value at a 25% higher rate than homes under that figure. But the conversion rate could be steepened and made more progressive by adding additional tiers. The first bracket of a home's value would be converted to taxable value at a low percentage; the next bracket would be converted at a higher rate, and highest remainders of a home's value would be converted at a still higher rate. That's the sort of progressive property taxation that Minnesota employed several decades ago.

For those prone to panic over the idea of a new city income tax, remember this. First, it would only apply to those over a relatively robust income level; in other words, those who can afford to pay. Second, the alternative is steadily increasing property taxes or a steady ebb in city services. And third, this can only be imposed if the City Council makes it part of its legislative proposal, and even then only if the Legislature grants Minneapolis the authority to impose it. That's not likely until before 2027, and chancy even then. That makes this a prime time to prepare a thoughtful proposal.

Neither I nor the board on which I serve has the authority to impose this idea. I admit that a tax increase is an unconventional way to campaign for re-election. If you want to take it out on me in November's election, go ahead. I was the leading vote-getter for my position in 2021. I could play it safe and likely get re-elected. But I figure that the job of a public official is to see problems and find solutions. I also believe that progressivity in taxation — taxing those who can afford it at a higher rate — is good for a healthy democracy. Feel free to send me your thoughts.

Steve Brandt, a retired Star Tribune reporter, has been a member of the Minneapolis Board of Estimate and Taxation since 2022. He may be reached at sbrandt51@gmail.com.

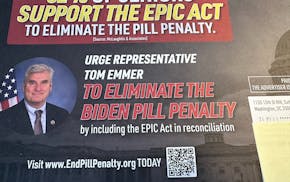

Burcum: About that so-called 'pill penalty'