Opinion editor's note: Strib Voices publishes a mix of guest commentaries online and in print each day. To contribute, click here.

•••

One of the key themes in the anti-DEI crusade is the assertion that attention to racial discrimination in educational settings causes undue guilt and emotional stress among young white people.

As a white person who grew up in the segregated U.S. South, I have no idea whether my ancestors were slave owners or directly supported the enslavement of people with African heritage. What I do know is that I benefited from the privileges attached to my "white" appearance and membership in a "white" family. I don't feel guilty about that. I only feel guilty if I fail to acknowledge my privilege and if I fail to try to use my talents and energy to work for a society in which everyone has an equal chance to flourish.

My father, a World War II Navy veteran and son of South Carolina sharecroppers, worked most of his adult life at the Savannah River Plant, a sprawling site for nuclear reactors near Aiken, S.C. Locally known as "the Bomb Plant," SRP's main product was plutonium. I also worked there one summer between my sophomore and junior years in college monitoring the turbidity of the heavy water that was part of the production process.

I don't feel guilty that my father and I contributed to appalling weapons of war — we both thought we were contributing to national security. I feel guilty only if I fail to bring attention to the threat of nuclear disaster and to support peace-building work within and across national borders.

Guilt seems to me to be like many emotions, a prompt to pay attention and take action. I don't desire that children or adults be overwhelmed by guilt, but rather that we see it as a message from our moral cores that we should seek understanding and pursue remedies to injustice.

My questions to those who are crusading against DEI programs (which admittedly vary in quality) are: What remedies for structural disadvantages would you offer? Can you pretend that these disadvantages don't exist? Do you think that the extreme and well-documented wealth disparities between U.S. Black and white households are simply due to luck or merit? Are poor white folks struggling because they don't work hard enough?

If you do recognize the barriers that keep some in our human family from thriving, but think remedies like affirmative action and programs emphasizing diversity, equity and inclusion are imperfect or completely wrong-headed, what do you recommend?

In general, I find most promising the "targeted individualism" approach developed by john a. powell, now director of the Othering & Belonging Institute at University of California, Berkeley, and a former faculty member at the University of Minnesota. The approach also aligns with Patrick Milan's recent call for blending progressive values and pragmatic leadership ("DEI is dead. Long live DEI," Strib Voices, April 21).

As the Othering & Belonging website explains, "Targeted universalism means setting universal goals pursued by targeted processes to achieve those goals. Within a targeted universalism framework, universal goals are established for all groups concerned. The strategies developed to achieve those goals are targeted, based upon how different groups are situated within structures, culture, and across geographies to obtain the universal goal."

For example, if the universal goal is to ensure that everyone has access to decent affordable housing, strategies would be tailored to different groups – for example, rural low-income residents, Black families, first-time homebuyers, renters, young people aging out of foster care, and so on. Yes, targeted universalism recognizes the significance of diversity, the desirability of equity and the democratic imperative of inclusion. In a country committed to democratic values, I believe infusing this approach into public policies is vital if everyone is to have a chance to thrive.

Let's convert whatever guilt we feel about unfair systems, exclusion and injustices into action.

Barbara C. Crosby is an associate professor emerita at the University of Minnesota's Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

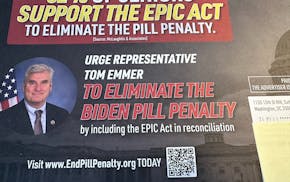

Burcum: About that so-called 'pill penalty'