Somewhere amid the heckling and the boos, the murmurs and groans, city officials tried to invoke his name, like a call to a higher power to silence the angry masses.

"There's even a popular book by an author named Donald Shoup called 'The High Cost of Free Parking,' " Barb Thoman, former director for Transit for a Livable Community, said to the crowd gathered to discuss parking meters along Grand Avenue in St. Paul.

Boooooooooooooo!

A few minutes later, Mayor Chris Coleman tried again: "Barb referenced Donald Shoup's book, and you don't have to believe me on this. …"

Boooooooooooooo!

A transcript of the contentious meeting, posted on the blog tcsidewalks.blogspot.com, captures the raucous nature of the Twin Cities biggest boutique battle of the moment — the desire of the city's mayor and his walk-and-bike devotees to make people pay for parking along St. Paul's quaintest shopping district.

In short, businesses and neighbors absolutely hate the idea by a wide margin, so much so that they showed up by the hundreds on a lovely fall evening to lambaste an incredibly popular mayor. So why do people get so hostile when it comes to something as seemingly benign as parking meters?

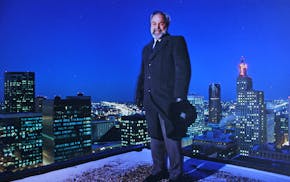

We turn to the guru of parking himself, a 77-year-old distinguished professor of urban studies at UCLA, with a Ph.D. in economics from Yale, for some answers: Donald Shoup.

"Thinking about parking seems to take place in the reptilian cortex, the most primitive part of the brain responsible for making snap decisions about urgent fight-or-flight choices, such as how to avoid being eaten," Shoup wrote in the preface to his 750-page book on parking. "The brain's reptilian cortex is said to govern instinctive behavior involved in aggression, dominance, territoriality, and ritual display — all important factors in cruising for parking and debating about parking policies."

So maybe it's not just that the reptiles of Grand Avenue are caught up in a mad rush to complete their set of Wüsthof knives or build the perfect charcuterie plate for the weekend party. Psychologically, they are trying to avoid being eaten.

It seems a bit of a stretch, but because Shoup is being cited around the globe on parking issues, let's hear him out. During a phone call from a road trip, Shoup discussed why Grand Avenue might benefit from parking meters, and what the city officials might be doing wrong to sell the idea.

Booooooooooooo!

Ok, Ok, let's give Shoup a chance.

Shoup has looked at lots of studies of parking in cities large and small. He argues that a large number of cars in congested traffic, say 30 percent, are circling blocks looking for parking, wasting time and creating pollution. If parking is priced right, and not limited so as to irritate someone trying to take in dinner and a movie, it will make shopping, dining and parking more efficient.

Shoup's parking Nirvana is something that can be measured and manipulated until a city, and the laws of supply and demand, find the "Goldilocks Principle: not too high, not too low, but just right," said Shoup. If the price for a meter is too high, there will be too many vacant spaces. If it's too low, there will be none. The optimum is about 85 percent full, or about one or two open spots per block at any time. "Demand sets the prices at the lowest it can charge without a parking shortage," Shoup said.

Shoup's notion of "performance pricing" works to ensure ample parking and better traffic flow. That might mean adjusting the price at certain hours.

But what about those customers who promise they will never set foot on Grand Avenue again if meters are installed?

"Everybody wants free parking, including me," said Shoup.

Currently, Shoup argues, people pay for parking in housing taxes and their time. If customers really abandon their favorite shops and restaurants because of a $2 meter, others willing to pay will fill that spot, as long as the meter is priced correctly. The idea will also dissuade employees from taking spots near their shop or restaurant.

"Who is going to leave a better tip, or buy more expensive items?" Shoup asked. "The person who is willing to pay for parking."

Where St. Paul may have erred, Shoup said, is in saying up front that the money gained by meters on Grand would go to the general fund.

"The political solution that has worked very well is to promise the neighborhood that some or all of the money would be spent on what they want the most," said Shoup. "It you say right up front, the city needs the money, it generates ill will. It's not illogical, but it's just impolitic. If you say, 'We need general revenue from your neighborhood,' it just doesn't seem fair."

Promising better lighting, snow shoveling or police presence, might help persuade people the meter money won't disappear into the ether, said Shoup.

If all that fails, Shoup has another tantalizing idea that may just resonate with critics: Offer discounts for neighbors and St. Paul city residents.

"They will pay a lower rate," said Shoup. "People from Minneapolis will pay more."

Talk about appealing to the reptilian cortex.

jtevlin@startribune.com 612-673-1702

Follow Jon on Twitter: @jontevlin

Depressed after his wife's death, this Minneapolis man turned to ketamine therapy for help

Tevlin: 'Against all odds, I survived a career in journalism'